There are few moments in Roman history that have been reduced so efficiently to a single image as Julius Caesar at the Rubicon. He pauses at a narrow river in northern Italy, the story goes, weighed down by destiny, murmurs something suitably grave, and steps into civil war. It is a scene that fits neatly into textbooks and documentaries because it offers clarity. One man. One choice. One turning point. History rarely works that way, and Rome least of all.

By the time Caesar reached the Rubicon in January of 49 BCE, the Republic had already done most of the damage to itself. The river did not force the crisis. It merely marked the place where Rome stopped pretending that its political system still functioned. What followed was not the sudden collapse of republican virtue under the heel of ambition. It was the end stage of a decade long process in which law had been bent, bypassed, and finally weaponized until it could no longer serve its original purpose.

The Rubicon itself was not imposing. It was a legal boundary more than a geographic one, separating Caesar’s province of Cisalpine Gaul from Italy proper. Roman law forbade a general from crossing that line under arms. To do so was to declare war on the state. Everyone involved understood the rule. What is less often emphasized is why that rule existed. The Republic feared concentrated military power within Italy. Armies belonged on the frontier. Politics belonged in the city. Once those roles blurred, Rome believed liberty followed them into the ditch.

That belief had already been undermined long before Caesar arrived at the riverbank.

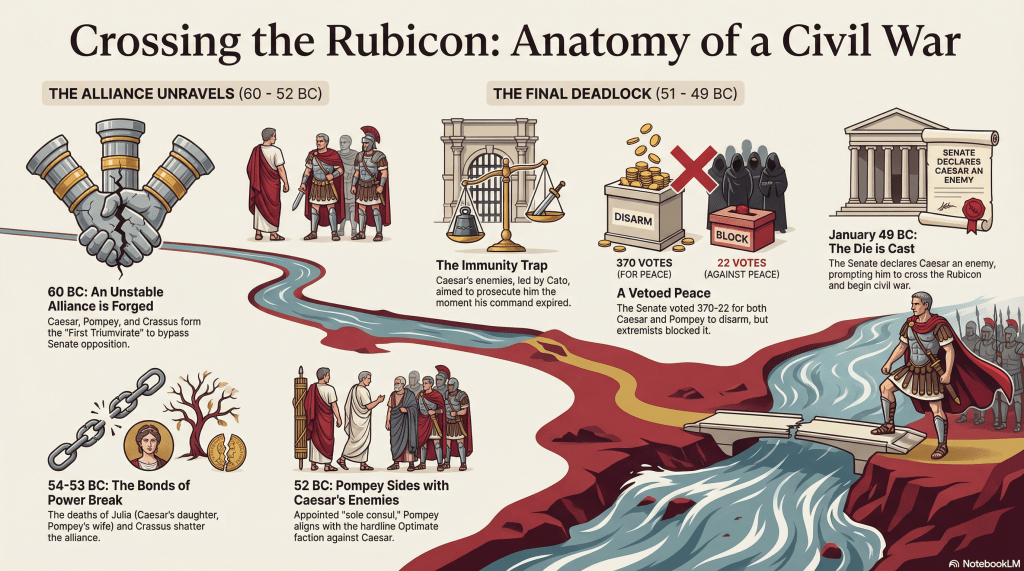

To understand how the Republic reached that point, it is necessary to revisit an alliance that was never legal, never formal, and never intended to endure. In 60 BCE, Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, and Marcus Licinius Crassus formed what later writers would label the First Triumvirate. They did not announce it. They did not swear oaths. They simply agreed to stop allowing the Senate to block their ambitions.

Each man came to the arrangement bruised by senatorial resistance. Pompey had returned from the eastern Mediterranean having reorganized provinces, settled client kings, and concluded wars that expanded Rome’s influence dramatically. He also returned to a Senate that refused to ratify his settlements or provide land for his veterans. Crassus, fabulously wealthy and politically frustrated, wanted relief for tax collectors in Asia and recognition equal to Pompey’s military fame. Caesar needed the consulship of 59 BCE and a provincial command long enough and lucrative enough to stabilize his finances and elevate his standing.

The Senate, particularly its conservative faction led by men like Cato the Younger, blocked them all. The Triumvirate was not an ideological alliance. It was a work stoppage. If the Republic would not function through its institutions, power would flow around them.

Caesar’s consulship demonstrated exactly how that arrangement would operate. His co-consult, Bibulus, attempted to obstruct legislation through traditional religious and procedural means. Caesar ignored him. When Bibulus declared the days unfavorable for public business, Caesar pressed forward anyway. When debate failed, presence prevailed. Veterans stood nearby. Crowds gathered. Laws passed not because consensus had been reached, but because resistance had become futile.

Among those laws was the Lex Vatinia, which granted Caesar a five-year command in Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, later expanded to include Transalpine Gaul. That command was the hinge on which everything else would turn. It provided Caesar with imperium, the legal authority to command troops and the immunity from prosecution that came with it. It also placed him beyond the immediate reach of Rome’s political enemies.

For a time, the system worked, if one is willing to call it that. Pompey received land for his veterans. Crassus secured financial concessions. Caesar went north and did what Roman generals were expected to do. He conquered, wrote dispatches, and built loyalty. His Commentaries framed the wars as defensive and necessary. His soldiers experienced something rarer than pay or plunder. They experienced continuity. Year after year under the same commander, success reinforced loyalty, and loyalty reinforced success.

The alliance was renewed in 56 BCE at Luca, where Caesar’s command was extended and Pompey and Crassus secured another consulship. It was an impressive show of coordination. It was also the moment when the countdown became unavoidable. Caesar’s term would end. At some point, he would have to return to Rome and reenter civilian life.

In an earlier Republic, that transition would have been uncomfortable but survivable. By the late fifties, it was becoming something else entirely. Political culture had hardened. Prosecution had become a tool of annihilation rather than accountability. Men were no longer merely defeated. They were ruined.

The Triumvirate had stabilized the system by ignoring it. It had not repaired it. When the personal bonds holding that arrangement together began to fail, there was nothing underneath to catch the fall.

That is where the Republic stood as Caesar’s victories accumulated in Gaul. Rome appeared outwardly stable, but the mechanisms that once allowed power to be shared and surrendered peacefully were already eroding. The Rubicon lay years in the future, but the path toward it had been set.

The arrangement that had kept Rome from tearing itself apart was always more fragile than its architects admitted. It depended not on law but on balance, not on institutions but on personalities. When those personalities changed, aged, or disappeared, the system had nothing left to lean on. The unraveling began quietly, through loss rather than confrontation, and like most political disasters, it was well underway before anyone was willing to say it aloud.

In 54 BCE, Julia died in childbirth. She was Caesar’s daughter and Pompey’s wife, and her marriage had been more than decorative. It was the only genuine personal bond tying the two most powerful men in Rome together. Caesar and Pompey had cooperated before, but their alliance was reinforced by family in a way Romans understood instinctively. With Julia gone, that bond vanished. The grief was real, but the consequences were political. Caesar moved quickly to preserve the connection, offering Pompey a new marriage alliance with his great niece Octavia. Pompey declined. It was done politely, even graciously, but the meaning was unmistakable. Pompey no longer wished to bind his future to Caesar’s.

The following year delivered a far more violent shock. In 53 BCE, Crassus was annihilated at Carrhae. His army was destroyed. He was killed. His head was paraded as a trophy. Rome lost not only a general and a fortune, but the one man who had served as a counterweight between Caesar and Pompey. Crassus had no illusions about republican virtue, but he understood leverage. He had wealth, ambition, and enough independence to keep the other two from locking horns too directly. With his death, the political landscape collapsed into something stark and unstable.

Rome was now divided between two figures who could not coexist indefinitely. Caesar was winning glory and loyalty in Gaul, far from the capital. Pompey was drifting back toward the center of Roman political life, rediscovering his usefulness to a Senate that suddenly found him indispensable. The Optimates, long hostile to both men, now made a calculation. Caesar was distant, unpredictable, and surrounded by soldiers. Pompey was present, prestigious, and increasingly willing to speak the language of order and tradition. The choice, for them, was obvious.

Events in Rome soon forced Pompey’s hand. By 52 BCE, political competition had devolved into open violence. Elections were disrupted by gangs aligned with rival factions. Street fighting became routine. The killing of Publius Clodius Pulcher, a populist agitator, triggered riots so severe that the Senate House itself was burned. The Republic’s most sacred political space was reduced to ash by its own citizens. No one could plausibly argue that normal governance still functioned.

The Senate responded in the only way it knew how. It concentrated power. Pompey was appointed consul without a colleague, an extraordinary measure justified as a temporary necessity. He was to restore order, stabilize the city, and then presumably step back. In reality, the appointment marked a decisive shift. Pompey was no longer a rival to the senatorial establishment. He was its champion.

Pompey’s legislation during this period reflected that alignment. Some measures appeared conciliatory. He supported a law allowing Caesar to stand for the consulship while absent from Rome, a crucial protection given Caesar’s position in Gaul. To outside observers, this looked like compromise. To Caesar, it looked like a delay.

Other laws cut deeper. The Lex Pompeia de Provinciis enforced a five-year gap between holding office in Rome and governing a province. On its face, the law promoted good governance. In practice, it created a lethal vulnerability. Caesar’s command would expire. His successor could be appointed immediately. The moment Caesar relinquished imperium, he would be exposed.

This was not a theoretical concern. Caesar’s enemies had been explicit. Cato the Younger had sworn to prosecute him for his actions during the consulship of 59 BCE. Whether such a prosecution would succeed was almost beside the point. Trials in the late Republic were political theater, shaped by alliances, juries, and atmosphere. To be hauled into court was to be publicly diminished. Dignitas, the social standing that defined a Roman statesman’s worth, could be destroyed long before a verdict was reached.

By the early fifties, it was increasingly clear that Caesar was not being asked to return to civilian life. He was being invited to walk into a trap. Pompey may have believed this was a manageable pressure tactic. The Optimates believed it was justice delayed. Caesar understood it as something else entirely. It was political annihilation dressed in legal robes.

The Republic still functioned on paper. Magistrates were elected. Laws were passed. Votes were taken. But the spirit that once allowed rivals to lose and live had evaporated. Power had become zero sum. In that environment, stepping down did not mean stepping aside. It meant stepping off a cliff.

The stage was now set. Caesar remained in Gaul, legally in command, increasingly isolated. Pompey stood in Italy, armed with authority but not yet with armies. The Senate believed it could force a resolution through pressure and procedure. What it did not grasp was that the system had already lost the trust of the men it was trying to constrain.

The Republic had taught its leaders that survival required strength, not submission. The consequences of that lesson were about to arrive.

By the end of 50 BCE, the Roman Republic was no longer drifting toward crisis. It was pressing its foot down on the accelerator while insisting that it still had the brakes under control. The political temperature had risen to the point where even gestures of compromise were treated as evidence of bad faith. Caesar remained in Gaul, still within the law, still holding imperium, still commanding an army that had grown accustomed to his leadership. Pompey remained in Italy, wrapped in senatorial authority, publicly committed to defending the Republic, privately uncertain how far events would carry him. Between them sat a Senate that had lost its ability to arbitrate power and had instead chosen sides while pretending not to.

At the center of the dispute was a problem that Rome had avoided addressing for generations. The Republic had no stable mechanism for transitioning men of extraordinary power back into civilian life. Imperium was absolute while it lasted, and its removal was absolute as well. There was no gradual handoff, no protected descent. A general either commanded or he did not. Once he did not, he stood naked before his enemies. For a figure like Caesar, whose rise had created as many resentments as loyalties, that vulnerability was existential.

The debate over Caesar’s motives has lingered ever since. Ancient writers like Suetonius suggested that Caesar feared prosecution and conviction. Modern scholars tend to doubt that a guilty verdict was inevitable. What is harder to dismiss is the fear of humiliation. In Roman political culture, reputation was substance. Dignitas was not a matter of ego. It was the foundation of authority. To be prosecuted was to be publicly declared unworthy of trust, stripped of honor, and reduced to a cautionary tale. Caesar had spent a decade accumulating glory. He was not prepared to watch it dismantled in a courtroom designed to make an example of him.

In this atmosphere, Gaius Scribonius Curio emerged as an unexpected advocate for restraint. Curio was a tribune of the plebs, charismatic, sharp tongued, and quietly subsidized by Caesar. He proposed a solution that many in the Senate had privately wanted but publicly avoided. Caesar and Pompey would both lay down their commands simultaneously. The Republic would be spared civil war. No one would gain an advantage through delay or maneuver.

The proposal forced clarity. If the crisis was truly about constitutional principle, mutual disarmament would solve it. If it was about power, the response would reveal as much. When the Senate voted on December first, the result was overwhelming. Three hundred seventy senators favored Curio’s motion. Twenty-two opposed it. The majority of Rome’s governing body wanted peace.

That should have ended the matter. It did not. The hardline faction, dominated by men who had staked their careers on Caesar’s destruction, refused to accept the result. Procedure was ignored. Authority was improvised. One of the consuls, Gaius Marcellus, bypassed the Senate entirely and went to Pompey, symbolically placing a sword in his hand and urging him to defend the Republic against Caesar. The act had no legal foundation. It did not matter. The dispute had crossed a threshold. Political conflict had been explicitly militarized.

Caesar watched these developments from Gaul with increasing clarity. The Senate’s vote for peace had been nullified. Pompey had accepted an extra-legal commission. The message was unmistakable. Caesar would be required to surrender his command unilaterally and trust his enemies to show restraint. Experience suggested otherwise.

Even so, Caesar made one final attempt. On January first, 49 BCE, he sent a letter to the Senate offering to resign his command if Pompey would do the same. It was a last effort to force symmetry and expose bad faith. The consuls refused to allow the letter to be debated. Time was now a weapon. Delay favored Pompey, whose resources and manpower dwarfed Caesar’s single legion in northern Italy.

The final rupture came days later. The tribunes Mark Antony and Quintus Cassius Longinus attempted to veto further action against Caesar, invoking the ancient protections of their office. They were threatened with violence. Their safety could no longer be guaranteed. Disguised as slaves, they fled Rome and made their way north to Caesar’s camp. The symbolism was devastating. The sacrosanctity of the tribunate, one of the Republic’s oldest safeguards against tyranny, had been openly violated by the Senate itself.

On January seventh, the Senate passed the Senatus Consultum Ultimum, the Final Decree. Martial law was declared. Caesar was effectively named a public enemy if he did not immediately disband his army. This was not a negotiation. It was a command backed by force and certainty that Caesar would comply.

He did not.

Caesar was at Ravenna with the Thirteenth Legion, roughly five thousand men. He moved quickly, not because he desired drama, but because speed was survival. Ancient accounts differ on the details of the crossing. Plutarch gives us hesitation. Suetonius gives us resolve. The phrase Alea iacta est captures the mood if not the exact words. The die was cast because the game had already been rigged.

Crossing the Rubicon was not an act of sudden rebellion. It was the acknowledgment that the Republic had already chosen war while insisting it was defending peace. Caesar advanced rapidly on Ariminum, shocking Pompey and the Senate, who had expected a slower, more deliberate campaign. Instead, they panicked. Rome was evacuated. The treasury was abandoned. The capital of the Republic was surrendered without a fight.

The Republic did not fall that day. It staggered on, issuing decrees and rallying armies. But the illusion was gone. Political deadlock would now be resolved by military force. Caesar did not create that precedent. He acted within it.

The Rubicon was a narrow river. Rome had spent years ensuring that once it was reached, there would be no turning back.

Leave a comment