There was never much suspense in Connecticut, not the kind that keeps men pacing the floor or whispering in corners. By the winter of 1788, the question was not whether the new Constitution would be ratified there, but how quickly the matter would be concluded and whether everyone would walk out agreeing, or merely resigned. Connecticut did not do drama particularly well. It did not cultivate political theater. It had a reputation, earned long before independence, for being steady to the point of dullness, a place where decisions were made by counting votes rather than by raising voices. That reputation mattered in January 1788, because it shaped both expectations and outcomes. Connecticut ratified the Constitution in mid January, becoming the fifth state to do so, a milestone that was celebrated at the time as carrying the process past the halfway point, even though everyone involved understood that nine states would never be enough in practice. A union ratified by only nine would not hold. A nation born half convinced would not survive. Connecticut knew this as well as anyone, which may explain why the debate there felt less like a struggle over ideology and more like the closing of an account long overdue.

To understand why Connecticut moved the way it did, it helps to understand how it usually moved. From its colonial beginnings, Connecticut cultivated stability as a civic virtue. It was not immune to disagreement, but it had a habit of containing it. When disputes arose, they were resolved through town meetings, elections, and conventions rather than through riots or pamphlet wars. Even during the years leading up to the Revolution, Connecticut hesitated longer than some of its neighbors. Early on, the colony elected a government that leaned toward reconciliation with Britain. This was not cowardice, nor was it loyalty in the romantic sense. It was caution, a belief that lawful continuity mattered, even in a time of grievance. When that leadership passed from the scene, Connecticut shifted course through elections rather than upheaval, aligning itself with the revolutionary cause in the same measured way it aligned itself with most things. Once committed, it sent men, supplies, and ships. It simply did not advertise its fervor. There were no great moments that lodged themselves permanently in the national imagination, no single battle or declaration that defined Connecticut’s role. The state did its work and returned home, which is why its contributions are often overlooked and why its ratification of the Constitution can appear, at first glance, almost inevitable.

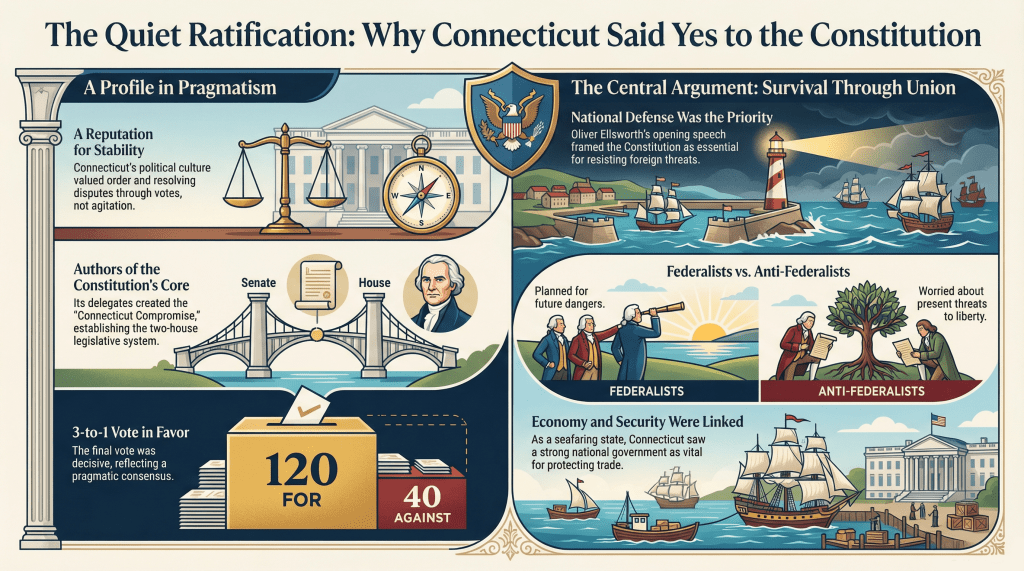

That sense of inevitability had less to do with temperament alone and more to do with authorship. The Constitution that came before the states in the fall of 1787 bore the unmistakable imprint of Connecticut. The central compromise that allowed the Philadelphia Convention to survive its worst internal crisis came from its delegates. Equal representation in the Senate balanced against proportional representation in the House was not a vague philosophical synthesis. It was a concrete proposal put forward by men who understood both large and small state fears and who knew that without such a bargain, the convention would collapse. The compromise carried the name of the state for a reason. Connecticut had provided the fulcrum on which the entire structure rested. For Connecticut to reject the finished document would have been an act of political self negation, a public declaration that its own solution was unfit for use. That reality hovered over the ratifying convention from the moment it was called. No delegate needed to be reminded of it, though it was certainly understood by all present.

The convention itself reflected Connecticut’s habits. Delegates were chosen town by town, preserving local legitimacy and reinforcing the idea that this was a decision owned by the people rather than imposed from above. Roughly one hundred sixty men gathered. There was debate, but it was restrained. There were objections, but they were specific rather than sweeping. When the vote was finally taken, the margin was substantial, roughly three to one in favor. The opponents were not silenced, but they were clearly outnumbered. Connecticut ratified without enthusiasm and without regret, which was perhaps the most Connecticut outcome imaginable. Yet even in this quiet decision, there were tensions that echoed far beyond Hartford, tensions that would shape the national debate in the weeks and months that followed.

One of the frustrations of studying Connecticut’s ratifying convention is how little of it survives in the historical record. Unlike Pennsylvania or New York, where transcripts, pamphlets, and correspondence allow historians to reconstruct arguments nearly word for word, Connecticut left behind fragments. There are speeches partially recorded, newspaper summaries, recollections written years later. Much is missing. The delegates did not seem to believe that posterity would demand a full account. They were making a decision, not staging a performance. For historians, this absence is both limiting and revealing. It forces attention onto what was considered important enough to preserve, and in Connecticut’s case, that turns out to be the opening argument rather than the closing vote.

When the convention opened on January 4, one voice set the tone immediately. Oliver Ellsworth, one of Connecticut’s principal architects at Philadelphia, addressed the assembly with an argument that assumed more than it explained. He began by observing that the proposed Constitution contained no preface, a curious omission for such a consequential document. The absence mattered, he suggested, because the Constitution presupposed two facts that no longer required debate. First, a federal government was necessary. Second, the Articles of Confederation had failed. From there, Ellsworth moved quickly to what he regarded as the central purpose of the new system. A union was required for national defense. Everything else flowed from that necessity. He did not linger on abstract theories of sovereignty or extended discussions of representation. He spoke instead of strength and vulnerability, of history’s lessons written in blood and conquest. United, states could resist external threat. Divided, they would fall, one by one, as others had before them. He pointed to the ancient world, to England’s own past, to peoples overwhelmed not by superior virtue but by superior organization. His conclusion was simple and unsentimental. Division invited destruction.

This emphasis on defense marked a subtle shift in the broader ratification debate. Earlier arguments had focused on whether union itself was desirable. By January 1788, that question was fading. The focus was moving toward how the union would protect itself and at what cost. In pamphlets circulating beyond Connecticut, Anti Federalist writers increasingly narrowed their attacks to specific features of the Constitution. Standing armies loomed largest among these concerns. A permanent military force, they argued, threatened liberty. It invited abuse. It created the possibility that power would rest not in law but in arms. These were not imaginary fears. European history offered ample examples. Ellsworth did not deny the danger. Instead, he reframed it. The danger lay not in defense itself, but in defense without structure. A system that placed the military under civilian control, funded by representatives, constrained by law, was not the same as an unchecked force loyal only to its commander. The Constitution, he argued, attempted to balance necessity against risk, not eliminate risk entirely. That was a theme that resonated in Connecticut, where the militia tradition coexisted with an understanding of maritime vulnerability and commercial exposure.

Connecticut’s economy and geography shaped these views in ways that were rarely spelled out but always present. This was a seafaring state. Its ports connected it to the Atlantic world. Its merchants understood that trade required protection, and protection required coordination. A navy could not be improvised town by town. An army could not be raised anew for every crisis. The Constitution’s provisions for national defense were therefore read not only as safeguards, but as opportunities. A stronger federal government meant contracts, shipbuilding, provisioning, and steady employment. None of this was articulated in the language of economic development, a phrase that would have sounded foreign in 1788, but the logic was clear enough. Stability bred prosperity, and prosperity depended on security.

As the debate unfolded, the contrast between Federalist and Anti Federalist thinking grew sharper. The Anti Federalists spoke in the present tense. They assessed the world as it appeared in early 1788 and found little to fear. Britain had been defeated. European powers were distant. The states were at peace. Why, they asked, should Americans surrender hard won autonomy to guard against hypothetical dangers? The Federalists answered in a different register. They spoke of uncertainty. They spoke of time. They argued that the most dangerous threats were not those visible on the horizon, but those that could not yet be seen. Nations rose and fell. Alliances shifted. Technologies changed. A government designed only for the present would fail its descendants. The Constitution, in their view, was not a guarantee of liberty, but a framework within which liberty might endure, if the people remained vigilant. This was not an argument that promised comfort. It offered responsibility instead.

Connecticut’s delegates seemed receptive to this argument precisely because it did not flatter them. It did not suggest that virtue alone would suffice. It did not claim that Americans were immune to the temptations that had undone other republics. It assumed fallibility and sought to manage it. That assumption aligned with Connecticut’s own political culture, which had long favored systems over personalities. The Constitution was ratified not because it was perfect, but because it was workable. It offered tools rather than assurances. It accepted risk while attempting to distribute it. In that sense, Connecticut’s vote was an act of realism rather than faith.

Looking back, it is tempting to read later events into that January decision. The echoes of future conflicts, including the Civil War, can seem almost audible in the arguments about union and division. Phrases that would later be associated with Abraham Lincoln appear in Connecticut newspapers decades earlier, reflecting a shared inheritance of political language and historical memory. Yet it would be a mistake to credit Connecticut’s delegates with foresight they did not claim. They were not prophets. They were problem solvers. They faced a confederation that could not defend itself, pay its debts, or command respect abroad. They chose a Constitution that offered a chance, not a cure. That choice carried consequences they could not fully anticipate, some of them dark, some of them enduring.

In the end, Connecticut ratified as it always had acted, deliberately, legally, with an eye toward continuity rather than rupture. It was not the first state, nor the last. It did not speak the loudest. It did not demand the most concessions. It accepted the Constitution as an imperfect instrument necessary for survival. That quiet decision mattered. It reinforced the legitimacy of the new system. It signaled that the Constitution was not merely the project of restless states or ambitious men, but a document capable of earning the assent of those most invested in balance and restraint. In an age that often equates passion with principle, Connecticut’s ratification stands as a reminder that some of the most consequential choices in American history were made without applause, in rooms where men argued carefully, voted soberly, and went home convinced that they had done the only thing that made sense at the time.

Leave a comment