January 3, 1945 arrived quietly in Texas, but the news that settled over Dallas was anything but. The wire stories spoke with the cautious gravity of wartime language, careful not to say too much and yet saying enough. Commander Samuel David Dealey, one of the most successful submarine skippers in United States naval history, was missing in action. His boat, USS Harder, was overdue and presumed lost. For families who had learned to read between lines, that phrase carried the weight of finality. The Tyler Morning Telegraph ran the story beneath a headline that tried to balance pride and dread, calling Dealey a valiant hero of the Pacific while admitting what everyone already feared, that one of the war’s most aggressive and effective commanders had vanished into enemy waters and silence.

Only months earlier, senior officers had been almost breathless in their praise. Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood, who commanded the Pacific Submarine Force and was not known for hyperbole, called Harder’s fifth war patrol “the most brilliant submarine patrol of the war.” He went further, stating flatly that Dealey’s record would never be equalled. Those words mattered because Lockwood had seen every patrol report that crossed his desk. He had read accounts of brilliance and blunders alike, and he knew the difference between daring and recklessness. His assessment was not a morale speech. It was an after-action judgment rendered by a professional who understood how thin the margin between legend and loss could be.

It would have been easy, then and now, to reduce Sam Dealey to a ledger entry. Ships sunk, tonnage destroyed, decorations awarded. That impulse has always followed submarine warfare, partly because submarines fight in secret and partly because numbers feel safer than stories. Yet Dealey mattered for reasons that went beyond arithmetic. He was not simply a beneficiary of good fortune or flawed enemy tactics. He was an architect of a style of undersea warfare that rejected caution when caution no longer served the mission. He pushed his boat toward charging destroyers instead of away from them. He trusted his crew, his instincts, and his understanding of the enemy’s psychology. In doing so, he helped bend the tempo of the Pacific war in ways that senior planners in Tokyo and Washington alike were forced to acknowledge.

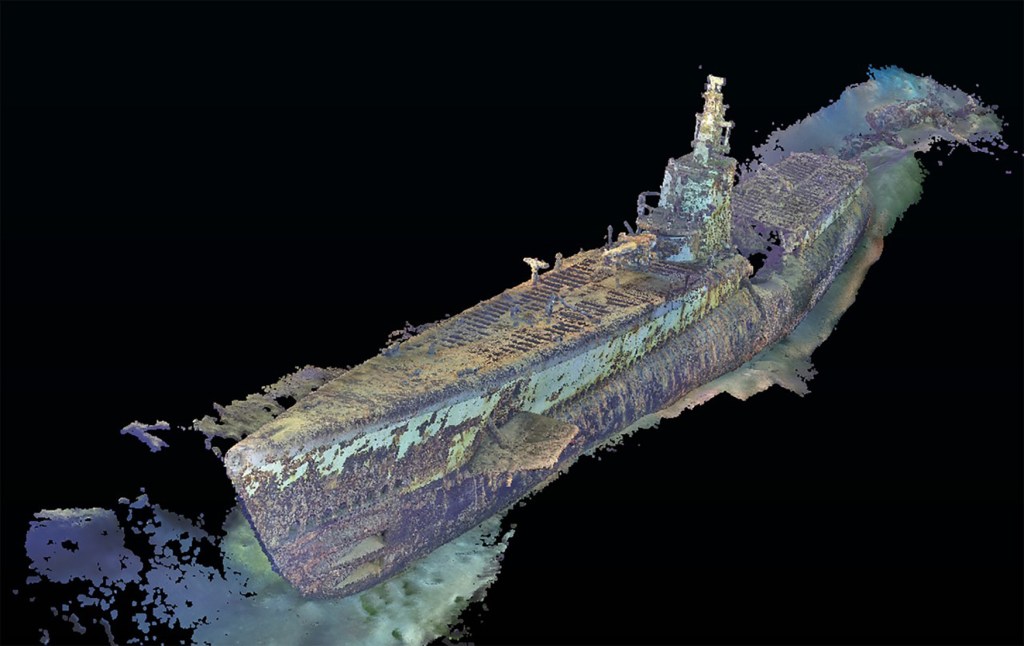

For decades, that story ended without a final chapter. Harder and her crew of seventy-nine men were listed among the missing. Their names were etched in stone, but their boat lay somewhere beyond charts and certainty. Then, in May 2024, the mystery closed. The Lost 52 Project located Harder off the coast of Luzon, resting upright on her keel more than three thousand feet below the surface. The wreck showed damage consistent with a fatal depth charge attack, matching Japanese records long held but never fully corroborated. The Naval History and Heritage Command confirmed the identification, and with that confirmation came a quiet but profound shift. The story was no longer just remembered. It was anchored in place and protected as a war grave.

What The Frock – The Musical

To understand how Sam Dealey reached that point, one must step back well before patrol reports and decorations. He was born on September 13, 1906, in Dallas, Texas, into a family whose name already carried weight. His uncle, George Bannerman Dealey, was the publisher of the Dallas Morning News and a civic force in his own right. The city knew the family, but privilege did not insulate young Sam from loss. His father died when Sam was still a child, prompting a move to Santa Monica, California. Even there, Texas retained its pull. He returned to Dallas to graduate from Oak Cliff High School, a decision that spoke to a sense of rootedness that would follow him throughout his life.

Dealey’s path to the Navy was not smooth, which in hindsight feels almost essential. He attended Southern Methodist University before securing an appointment to the United States Naval Academy in 1925. At Annapolis, he struggled academically and eventually failed out, an outcome that would have ended many careers before they began. Instead, Dealey did what would become a pattern. He fought his way back. Through persistence and support, he won reinstatement and graduated in June 1930. His classmates remembered him as “Tex,” a man with a never-failing sense of humor who could smile through pressure. That quality mattered more than yearbook writers could have known. Submarines are unforgiving places, and humor, when properly timed, can be as essential as discipline.

His early service did not point directly toward legend. He served aboard the battleship USS Nevada and the destroyer USS Rathburne, learning surface warfare before turning toward the silent service. In 1934, he attended Submarine School, followed by assignments on S boats and larger V boats, including Nautilus and Bass. These were not glamorous commands. They were classrooms disguised as steel hulls, teaching patience, mechanical sympathy, and the consequences of error. By the time war loomed, Dealey was commanding USS S 20 out of New London, conducting experiments that refined his understanding of what submarines could do when pushed beyond conservative doctrine.

When Dealey was assigned as the prospective commanding officer of a new Gato class submarine named Harder, the timing was stark. The keel was laid at Electric Boat just days before Pearl Harbor. By the time she was commissioned on December 2, 1942, the Navy was still learning, painfully, how to fight a modern submarine war. Harder would never have another commanding officer. From her commissioning to her loss, she belonged to Sam Dealey, for better and for worse.

Her early months tested that bond. During shakedown in the Caribbean in May 1943, Harder was mistakenly attacked by a United States Navy PBY Catalina patrol aircraft while operating in a designated safety lane. Bombs and machine gun fire tore into the water around her, a brutal reminder that submarines were vulnerable not only to the enemy but to misunderstanding. Dealey brought his boat through without loss, but the incident left its mark.

So did the machinery. Harder was fitted with Hooven Owens Rentschler diesel engines, notorious for unreliability. Her early patrols were also plagued by the Mark 14 torpedo, a weapon whose defects were costing lives across the Pacific. On her first patrol in June 1943, Harder’s initial attack ended with a premature torpedo explosion and an immediate counterattack that drove the submarine into the muddy seabed. It was an inauspicious beginning, and yet Dealey and his crew clawed their way free, later damaging the seaplane tender Sagara Maru despite everything working against them.

These were the conditions that forged Harder and her skipper. Not triumph, but defect and frustration. The Navy eventually sent Harder to Mare Island to have her engines replaced with General Motors diesels, a decision that transformed the boat’s reliability and set the stage for what followed. By then, Dealey had learned how to fight with imperfect tools, how to keep men steady when confidence wavered, and how to press forward without illusion.

That knowledge would soon collide with opportunity, and with enemy destroyers that had no reason to expect what was coming.

By the spring of 1944, USS Harder was no longer an experiment struggling against faulty equipment. She was a sharpened instrument, and Sam Dealey knew it. The refit at Mare Island had done more than replace engines. It restored confidence, both mechanical and human. Submarine warfare is intimate work. The captain’s belief in his boat transfers directly to the men who must trust every valve, every bearing, and every order given in darkness. Dealey came out of that yard period with a boat that answered the bell and a crew that believed their luck had finally aligned with their skill.

The fourth war patrol began with an episode that revealed more about Dealey’s character than any tonnage report could. On April 1, 1944, a Navy pilot, Ensign John Galvin, was shot down near Woleai Atoll and clung to life on a reef held by Japanese forces. Rescue by submarine was never a tidy affair. It required surfacing in confined waters under rifle fire, with no margin for mechanical failure. Dealey did not hesitate. He brought Harder in close, nosing her hull against the reef while Japanese snipers fired from shore. Galvin was hauled aboard under fire, a living reminder that submarines were not only instruments of destruction but also lifelines when no one else could reach. The act earned little immediate publicity, but it circulated quietly through the force, reinforcing Dealey’s reputation as a commander who accepted risk when the stakes were human.

Twelve days later, Harder encountered the Japanese destroyer Ikazuchi. Destroyers were designed to kill submarines. Doctrine taught evasion, patience, and withdrawal. Dealey chose none of those. As Ikazuchi closed, Harder turned toward her pursuer, closed the range, and fired. The destroyer sank within minutes. It was not the first time a submarine had sunk a destroyer, but it was the manner that unsettled observers. Dealey was not reacting. He was hunting.

That instinct reached full expression on the fifth patrol, the one that would define Harder’s place in naval history. In May 1944, Dealey requested assignment to the waters around Tawi Tawi, a major Japanese fleet anchorage in the southern Philippines. The request itself was audacious. Tawi Tawi was guarded by destroyers and patrol craft precisely because it was considered too dangerous for submarines to linger. Dealey understood that danger worked both ways. A force that believes itself secure tends to grow predictable.

Beginning on June 6, Harder entered what can only be described as four days of controlled violence. On that first day, she encountered the destroyer Minazuki. As the Japanese ship charged, Dealey executed what became known as the down the throat shot, firing directly at the bow of an onrushing enemy. It was an act that defied instinct. Closing distance reduced reaction time and magnified consequences. It also nullified evasive maneuvering. Minazuki exploded and sank, a shock to the destroyer screen that had never imagined itself prey.

The next day brought Hayanami. The engagement occurred at a range of roughly six hundred fifty yards, so close that there was little room for doubt or correction. Harder fired, and Hayanami vanished in fire and water. Two days later, on June 9, Tanikaze met the same fate. On June 10, Dealey pressed further, attacking a larger task force and firing on another destroyer before crash diving as explosions rolled overhead. Harder survived the counterattack, but the effect on Japanese command thinking was immediate.

Japanese Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa concluded that Tawi Tawi was surrounded by a large concentration of American submarines. In reality, the havoc was being wrought by a single boat operated with relentless aggression. Ozawa ordered the Mobile Fleet to sortie early, disrupting Japanese plans and contributing directly to the chaos that followed during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The decision was strategic, not tactical, and it traced back to one submarine commander’s refusal to behave as expected. For this, General Douglas MacArthur awarded Dealey the Army Distinguished Service Cross upon Harder’s return to Australia, an unusual honor that underscored how far the impact had rippled beyond the submarine force itself.

Yet success came at a cost that was already visible. Dealey returned from the fifth patrol exhausted. Rear Admiral Ralph Christie, his immediate superior, urged him to relinquish command. The suggestion was not a rebuke. It was concern. Dealey had carried the boat through five patrols, each more intense than the last. One third of the crew had been replaced with green hands. The safe course would have been to step aside and let another officer take the boat forward.

Dealey refused. His reasoning was simple and stubborn. He did not want a new skipper breaking in inexperienced men under combat conditions. He believed it was his responsibility to see them through their first patrol before handing the boat over. Christie reluctantly agreed. The decision would echo long after both men were gone.

Harder departed on her sixth patrol on August 5, 1944, as part of a coordinated operation with USS Haddo and USS Hake. The patrol area lay off Luzon, in waters thick with traffic and danger. Early successes came quickly. Off Paluan Bay and near Bataan, Harder sank the Japanese frigates Matsuwa and Hiburi. Haddo expended her torpedoes and departed the area, leaving Harder and Hake to continue the patrol together.

On the morning of August 24, 1944, the two submarines lay off Dasol Bay. Two Japanese ships emerged from the bay, the escort vessel CD 22 and Patrol Boat Number 102, which was in fact the captured American destroyer USS Stewart, now serving under a Japanese flag. At 6:47 a.m., the commander of USS Hake sighted Harder’s periscope ahead, six to seven hundred yards away. Moments later, CD 22 turned and charged.

Hake dove deep and rigged for silent running. From below, her crew listened. At 7:28 a.m., they heard a rapid string of fifteen depth charges, close and unmistakable. Then there was nothing. No further explosions. No sounds of pursuit. Harder did not answer calls. She was never heard from again. Japanese records later confirmed that CD 22 had evaded Dealey’s torpedoes and delivered the fatal attack, ending the career of the most aggressive submarine commander the Pacific had known .

The sea closed over Harder as it had over so many boats before her. For decades, that silence endured.

For eighty years, the end of USS Harder existed only as a convergence of testimony, inference, and absence. Survivors aboard USS Hake had heard the depth charges. Japanese records had noted the engagement. Families had lived with phrases like overdue and presumed lost. The boat herself remained beyond reach, an unmarked grave somewhere beneath the western Pacific. That uncertainty mattered more than outsiders often understood. Sailors can accept loss. What gnaws at them is the not knowing, the sense that a story has been interrupted mid-sentence.

In May 2024, that interruption ended. The Lost 52 Project, led by Tim Taylor, located the wreck of Harder off the coast of Luzon at a depth exceeding three thousand feet. The submarine lay upright on her keel, her shape unmistakable even after decades on the seabed. Photogrammetry revealed damage aft of the conning tower consistent with a concentrated depth charge attack, aligning precisely with Japanese action reports from August 24, 1944. The Naval History and Heritage Command confirmed the identification, closing the historical loop that had remained open since the war years.

The condition of the wreck told a restrained but eloquent story. Harder was not shattered or scattered. She appeared to have been killed cleanly, if such a phrase can be used at all. There was no evidence of a prolonged chase or repeated attacks. The depth charges had done their work quickly. For the families of the seventy-nine men aboard, that mattered. It suggested that the end came without prolonged terror, that the boat had not lingered helplessly beneath the sea. Closure does not erase grief, but it does change its shape.

With the wreck identified, Harder was formally recognized as a protected war grave. She would not be disturbed. Her crew, listed for decades on the Walls of the Missing, were finally home. The language used by the Navy was careful and spare, but the significance was immense. History had regained its final paragraph.

The passage of time also allowed for a clearer view of Sam Dealey’s legacy, including its complications. Few officers of the Second World War accumulated decorations at the pace Dealey did. He received the Medal of Honor, four Navy Crosses, the Army Distinguished Service Cross, and the Silver Star. He ranked among the most decorated naval officers of the conflict, fifth among submarine skippers by some measures. Yet even here, controversy intruded. Admiral Thomas Kinkaid initially blocked the Medal of Honor nomination, partly due to inter service friction and partly due to personal animosity toward Admiral Christie, who had championed Dealey’s case. The award was eventually approved with strong backing from General MacArthur and presented to Dealey’s widow, Edwina, in 1945.

There were also questions of accounting. Wartime claims credited Dealey with sinking six destroyers. Postwar analysis by the Joint Army Navy Assessment Committee reduced that figure to four destroyers and two frigates. The revision did not diminish his standing. No other American submarine commander sank destroyers with such frequency, regardless of classification. The argument over numbers misses the larger truth. Destroyers were hunters, not prey, and Dealey turned that equation inside out.

Memorials followed in predictable places and some unexpected ones. USS Dealey was commissioned in 1953, carrying his name into the Cold War Navy. The Dealey Center theater at Submarine Base New London ensured that generations of submariners would encounter his story early in their training. Plaques appeared in Dallas and at the Manila American Cemetery. Submarine Veterans of World War Two assigned Harder to the state of Utah, creating a memorial far from any ocean, a reminder that service and sacrifice are national rather than coastal inheritances.

What endures most powerfully, however, is not the hardware or the honors. It is the example of a commander who understood that warfare is conducted by people, not abstractions. Dealey was aggressive, sometimes frighteningly so, but he was not careless. He knew when to push and when to accept risk. He understood the enemy’s expectations and used them against him. He accepted responsibility for his crew in ways that went beyond regulation, even when that sense of duty led him back to sea one last time.

The discovery of Harder’s wreck does not turn tragedy into triumph. It does something quieter and more honest. It restores continuity. The men who sailed aboard her are no longer missing. They are located, remembered, and accounted for. As Samuel Cox of the Naval History and Heritage Command observed, Harder was lost in the course of victory, and victory has a price, as does freedom. That statement does not ask for applause. It asks for memory.

Sam Dealey remains on what submariners call eternal patrol. The phrase is not sentimental when understood correctly. It means that his story, and the story of USS Harder, continues to move beneath the surface of naval history, shaping how risk, courage, and command are understood. Not as legend polished smooth by time, but as a record of decisions made under pressure, with consequences that still matter.

The sea kept him for eighty years. History has him now, intact and unavoidably human.

All photos courtesy of NAVSOURCE.net

Leave a comment