In one of the episodes of the masterful HBO series, ROME, the lead character becomes concerned about the future. He expresses to his friend the eternal question:

Who will pour out libations for me?

Who will made offerings to the gods for my soul?

I keep coming back to that question because it refuses to stay where I first encountered it. It does not remain safely tucked into ancient poetry or ritual description. It follows me into archives, into old cemeteries, into casualty lists and service records, and sometimes into the quiet moments when the noise finally drops away and there is nothing left to distract me from it. Who will pour out the libation… for me?

The first time I read that question, it struck me as oddly blunt. Who will pour wine for me when I am gone? Who will make offerings for my soul? There was no poetry smoothing the edges, no theology cushioning the fear. It sounded like a human voice speaking plainly about something that mattered.

The trouble is that the question never actually goes away. Strip it of wine and altar stones and talk of souls, and it becomes one we ask constantly, even if we disguise it with different language. When I am gone, will anyone remember that I was here? Not as a statistic. Not as part of a trend or a movement. As a person who lived a specific life, with specific worries and affections, and then vanished.

What The Frock – The Musical

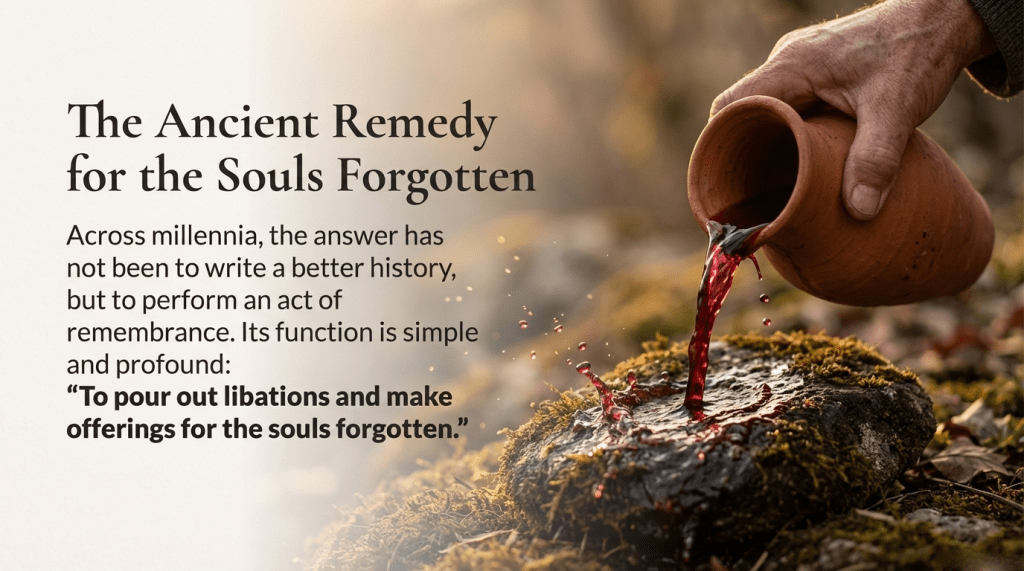

In the ancient world, a libation was a direct answer to that anxiety. Wine, oil, milk, honey, or water was poured onto the ground, onto a grave, onto a hearth, sometimes onto bare earth where no marker survived. The act was small, but it was intentional. Someone had to stop what they were doing. Someone had to decide that the dead were worth remembering. The liquid soaked into soil or disappeared into flame, and that disappearance mattered. The offering was gone, just as the person was gone, but the act itself stood as evidence that the dead had not been abandoned.

We tend to misunderstand this practice. We talk about libations as if they were meant to feed ghosts or bribe gods. That misses the point entirely. Libations were not about the dead demanding attention. They were about the living refusing silence. They were about acknowledging that a life did not cease to matter simply because it ceased to be useful or visible.

Once I began paying attention, I saw this impulse everywhere. Judaism preserves it through the Yahrzeit, the annual lighting of a candle and the recitation of prayer, a reminder that memory is an obligation, not a mood. Catholic Christianity maintains it through All Souls Day, a moment set aside not for heroes or saints but for ordinary dead who never entered the historical spotlight. China observes the Qingming Festival, communal rather than tied to a single date, where families tend graves and feed memory as shared labor. Mexico celebrates Día de los Muertos, vibrant and defiant, refusing to pretend that death cancels affection. Hindu and Islamic traditions carry their own forms of remembrance as well, quieter perhaps, but no less deliberate.

Different cultures, different languages, different foods on the table, but the same anxiety beneath it all. Human beings do not want to vanish completely. They do not want the people they loved to vanish either.

That realization makes me increasingly uneasy with how we in the modern West talk about memory. Somewhere along the way, we convinced ourselves that remembering could be outsourced. We built archives and libraries. We raised monuments and memorials. We carved names into stone and bronze. We established national days of remembrance and assumed the work was finished. We told ourselves that history would take care of it.

History cannot do that job.

This is not an attack on historians. It is an acknowledgment of the limits of the craft. History, as written, can never capture every thought, every fear, every small decision that made up a human life. It selects and compresses. It filters and prioritizes. It is editorial and subjective by necessity, not because historians are careless or cruel, but because no mind can hold everything.

We all know the big stories. We know Troy. We know the Black Plague. We know Julius Caesar. We can talk about causes, consequences, turning points, and legacies. We can argue about dates and interpretations and responsibility. But the big stories come at a cost. They flatten human lives into background noise.

How many Greeks died at Troy for the Trojan insult of Menelaus? We know the heroes. We know the speeches. We know the poetry. We do not know the names of most of the men who died because a king felt humiliated. They vanish behind the banner of epic.

How many people died in the Black Plague? We can offer numbers. We can debate mortality rates and regional variation. We can cite wills, burial records, and parish lists. We still cannot name the individuals who held dying children, who locked doors in fear, who stepped into the street one morning and did not return.

What about the legionnaires who marched under Caesar? Rome offers one of the clearest examples of this tension. We remember the general. We remember the ambition. We remember the speeches and the betrayal. We forget that every mile Caesar advanced was carried on the backs of men whose names never made it into the record.

This is one of the reasons Rome continues to matter to me. Rome understood, even if imperfectly, that public history and private memory were not the same thing. Rome raised monuments and wrote histories, but Romans also poured libations, tended tombs, and carved modest gravestones that listed little more than a name, an age, and an occupation. A baker. A soldier. A freedman. A child. Those stones were not competing with history. They were correcting it.

I was taught, as many were, that history is not there for you to like, a phrase often attributed to E. H. Carr. That is true. History is not meant to flatter or comfort. I was also taught that history exists to stop us from repeating the mistakes of the past, a line often traced to Santayana. That idea contains truth as well.

What troubles me is how often those ideas are misused. When history is treated only as a cold record to be endured or a warning label to be obeyed, it becomes detached from the people who lived it. The dead turn into examples. Their lives become tools. Carr would be appalled at the way his statement has become a meme that no longer reflects his intent. Today, when someone posts that quote (most often misattributed), what they mean to say is, “What I have decided is History is what YOU must accept.”

I am three generations removed from the American Civil War. That is not very far. It is close enough to find names, service records, pension files, and photographs. And yet I find myself asking an uncomfortable question. Do I actually remember them? Not the war. Not the arguments. The men themselves.

This is what bothers me. I have stood at the grave of a man, my paternal great-great-grandfather, who died fifty years before I was born and who served in that war. I placed upon his stone a few coins, a military tradition to remind each other to never forget those who have moved on. But I never knew him. I know literally, nothing about him except his name and the names of his child, my great-grandfather, and his child, my grandfather, and his child, my father.

I know the big story. I can explain causes and consequences. I can talk about strategy and politics and aftermath. But the individual lives dissolve quickly. They become uniforms. They become casualty figures. They become abstractions.

That distance is not accidental. It is built into how we are taught to think about the past. We remember events. We remember leaders. We remember outcomes. We forget people.

And that is where the question returns, quietly and insistently: Who will pour out the libation for me?

The more I think about it, the more I realize that forgetting people is not a side effect of history. It is built into the way we practice it. We are trained to look for causes and consequences, for movements and outcomes, for decisions that changed the course of events. We are not trained to linger with the people who were carried along by those decisions. We are taught to admire the architecture of the past, not to ask who mixed the mortar.

That habit begins early. In school, history arrives as a sequence of chapters with clear boundaries. One war ends, another begins. One administration gives way to the next. Names appear and disappear with tidy efficiency. The messiness of lived experience rarely intrudes. People become representatives of forces larger than themselves. They stop being people.

I understand why this happens. History has to be teachable. It has to be compressible. It has to fit into a syllabus, a book, a lecture, a radio segment. But the cost of that compression is easy to ignore until you start noticing who is missing.

Once you notice, it is hard to stop.

I think about Rome again, because Rome makes this problem impossible to avoid. Roman history survives in abundance. We have names, dates, inscriptions, biographies, speeches, and monuments. We can reconstruct campaigns and political struggles with impressive precision. And yet, for all that detail, most Romans remain invisible. The Republic and the Empire were not built by senators and generals alone. They were built by farmers, laborers, craftsmen, soldiers, and slaves whose names were never meant to last.

The Romans knew this, even if they did not articulate it the way we would. That is why private remembrance mattered. That is why families poured libations. That is why tombstones listed trades and ages instead of victories. Those small acts acknowledged what public history could not. They said, “this person existed, even if the Empire did not bother to remember them.”

That distinction feels increasingly important now, because we live in a culture saturated with information and starved for memory. We can access more historical data in a few minutes than previous generations could in a lifetime. We can summon documents, photographs, and maps instantly. And yet, for all that access, we often engage with the past in a strangely shallow way. We skim. We scroll. We consume.

Remembrance requires something different. It requires time. It requires attention. It requires choosing to care about someone who can no longer reward you for it.

That is what a libation demands. It demands that you stop. It demands that you acknowledge a life that no longer has a voice. It is not efficient. It is not productive. It does not scale well. That may be why it makes modern people uncomfortable.

I think about this often when I look at military history, especially in the twentieth century. Wars are presented as vast machines, grinding forward under the weight of industrial power and political will. We talk about divisions and corps, about production numbers and casualty totals. Those figures matter. They tell us something real about the scale of what happened. But they also make it easy to forget that every number represents a person who had a last ordinary day.

Veterans understand this instinctively. Anyone who has served knows how quickly individuality disappears once you are folded into a unit. You become a rank, a role, a body in formation. That does not erase who you are, but it does obscure it. When the war ends, the public tends to remember the victory or the failure, but not the men and women who carried it.

That is not cruelty. It is distance.

History widens that distance over time. The faces blur. The names fade. The war becomes a chapter. The chapter becomes a paragraph. Eventually, it becomes a sentence that begins with the words during the war.

That process is inevitable. What is not inevitable is accepting it without resistance.

When I say that I believe Western culture has forgotten how to remember, I do not mean that we are callous. I mean that we have confused documentation with remembrance. We assume that if something is recorded, it is remembered. We assume that if a name is carved into stone, the work is finished.

It is not.

A name on a wall does not speak unless someone reads it. A date on a calendar does not matter unless someone pauses to mark it. Memory is not passive. It does not happen automatically. It has to be practiced.

This is where the older rituals start to make sense again, even if we no longer share the beliefs that shaped them. Lighting a candle on a Yahrzeit is not about theology alone. It is about interruption. It breaks the flow of ordinary time and says, stop, remember this person. Tending a grave during Qingming is not about superstition. It is about maintenance. It says memory decays if you do not tend it. Setting a place for the dead during Día de los Muertos is not denial. It is acknowledgment. It says, you are gone, but you are not erased.

These practices exist because history cannot do their job for them. History explains. Ritual remembers.

I think again about my own distance from the Civil War. Three generations (on my maternal side) is nothing in historical terms. It should feel close. And yet it does not. I can name battles. I can describe political tensions. I can quote speeches. But the men themselves remain hazy. They exist as silhouettes, not as people with habits and tempers and private fears.

That realization unsettles me, because it suggests that time alone is not responsible for forgetting. Forgetting happens because we allow it to happen. We let the big story crowd out the small ones. We let efficiency replace attention.

Pouring out the libations of history is my way of pushing back against that drift. It is not about reenacting ancient rituals or romanticizing the past. It is about acknowledging a permanent gap in how history works. History will always be incomplete. There will always be more to learn, more to gather, more to understand.

But there will also always be people who slip through the cracks.

When I think of history as a map, I am reminded that maps are useful precisely because they leave things out. They show you where to go, not what it feels like to walk there. They do not show the crushed grass along the road or the stones that cut your feet. They do not show the places where someone stopped to rest and never got up again.

Libations are about those places. They are about the points where the map goes silent.

This is not an argument against history. It is an argument for humility. It is a reminder that understanding is not the same thing as honoring. You can understand a war perfectly and still fail to remember the people who fought it.

I do not believe history is there to make us feel good. I agree with Carr on that. I also believe Santayana was right to warn about forgetting. But I think both ideas fall short if they are treated as the whole purpose of studying the past. History is not only a lesson and not only a warning. It is also a record of loss.

And loss demands acknowledgment.

That acknowledgment does not have to look the same in every culture or every era. It does not have to involve wine or candles or festivals. But it does have to involve intention. Someone has to decide that the forgotten are worth remembering.

That decision is never made by history itself. It is made by the living.

And that brings me back, again, to the question that will not leave me alone. Who will pour out the libation for me?

The question keeps circling back, not because it demands an answer, but because it demands attention. Who will pour out the libation for me. It is not a question about ritual in the narrow sense. It is a question about whether anyone will stop long enough to acknowledge that a particular life once occupied a particular space in the world.

What unsettles me is how easily modern life encourages us to glide past that responsibility. We are busy. We are efficient. We are surrounded by reminders that everything must justify itself by producing something measurable. Memory does not fit neatly into that system. You cannot quantify the value of standing quietly and remembering someone who no longer has a claim on your time. There is no obvious return on investment.

That is precisely why remembrance matters.

When cultures forget how to remember, they do not become cruel overnight. They become thin. The past becomes flatter. The people in it become interchangeable. Suffering becomes abstract. Sacrifice becomes rhetorical. Once that happens, it becomes easier to speak about lives as if they were expendable, because in memory they already are.

I see this whenever history is reduced to talking points. Wars become arguments rather than experiences. Deaths become numbers rather than absences. The language grows clean and efficient, and something essential disappears with it. The past stops resisting us.

Libations resist. They slow things down. They insist on a pause. They ask for a moment of discomfort, a moment when nothing is being achieved except acknowledgment. They remind us that the dead do not need us to explain them. They need us to remember them.

This is why I do not think of pouring out the libations of history as an exercise in sentimentality. Sentimentality smooths the past. It makes it harmless. Libation does the opposite. It confronts you with the fact that someone lived and died and is now dependent on the living for memory. That is not comforting. It is sobering.

I think again of Rome, not the marble and the legions, but the ordinary Romans whose names survive only because someone cared enough to carve them into stone. A man who baked bread. A woman who lived twenty five years. A child who lived three. Those inscriptions do not explain history. They interrupt it. They force you to acknowledge that the Empire was made of lives that did not make speeches or issue decrees.

That interruption is what I am after.

History will always be selective. It will always privilege certain stories over others. That is unavoidable. What is avoidable is the assumption that whatever history does not record does not matter. That assumption is not neutral. It shapes how we see both the past and the present.

When I look at the distance between myself and the Civil War, what troubles me is not that I cannot remember everything. That would be impossible. What troubles me is how quickly individual lives fade once they are no longer useful to the narrative. I can tell you why the war happened. I can tell you how it ended. I struggle to tell you who the men were when they were not fighting.

That is the gap libations exist to fill.

They do not give you answers. They give you responsibility. They say, someone must remember, even if the remembering changes nothing. Even if no one sees it. Even if it produces no insight.

That kind of remembering does not fit well into modern categories. It is not scholarship. It is not activism. It is not entertainment. It is closer to maintenance. The same kind of work that keeps a grave from disappearing under weeds or a name from slipping out of use.

Maintenance is rarely glamorous. It is also what keeps things from collapsing.

I do not believe history is there to make us feel good. I also do not believe it excuses us from remembering. The past is not a lesson plan designed to improve us. It is a record of lives lived under conditions they did not choose. Many of those lives ended without recognition. That does not mean recognition is unnecessary. It means it was deferred.

Someone still has to do it.

Pouring out the libations of history is my way of naming that obligation. It is a reminder that the past is not only something to be studied, debated, or used. It is something to be tended. Not completely. Not perfectly. Just enough to keep it from vanishing entirely.

The question remains, as it always has. Who will pour out the libation for me. It does not ask for certainty. It asks for willingness. It asks whether anyone will stop long enough to acknowledge that a particular life mattered, even when it no longer matters to history.

That responsibility does not belong to institutions. It does not belong to textbooks. It does not belong to monuments. It belongs to people.

It belongs to the living.

And if we are honest, that is what makes the question uncomfortable. Not because it is ancient, but because it is still waiting for an answer.

The Debate:

Leave a comment