George Catlett Marshall is one of those figures whose importance becomes clearer the longer one studies him and more puzzling the more one tries to summarize him neatly. He does not lend himself to slogans or cinematic shorthand. There is no single moment that captures him, no battlefield pose that defines his legacy. Instead there is a long accumulation of decisions, habits, and silences that, taken together, helped shape the American century. He was the only American to serve as Army Chief of Staff, Secretary of State, and Secretary of Defense, and he did so without ever behaving as though history owed him attention. That alone should give modern audiences pause.

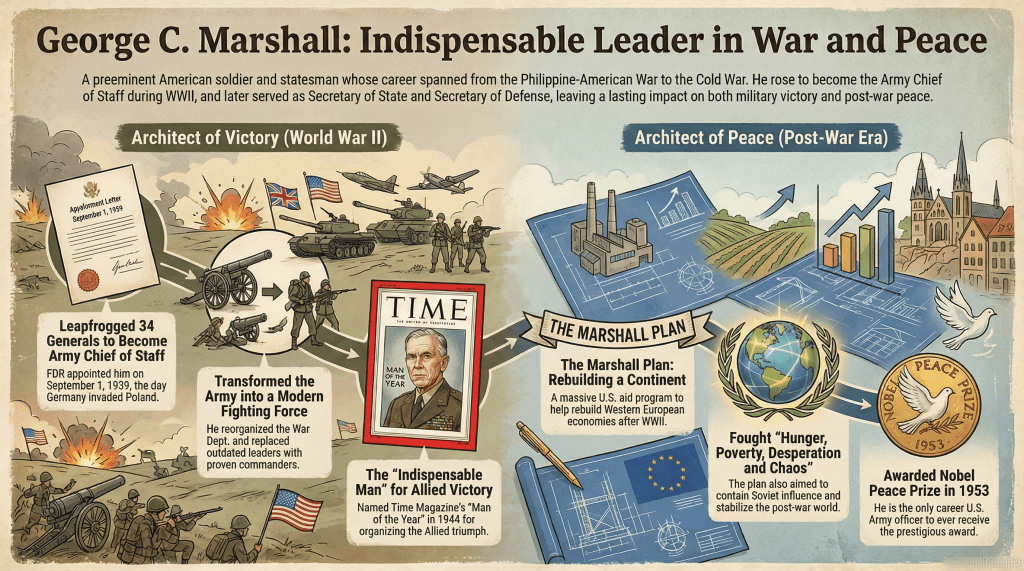

Marshall was never interested in being admired. He was interested in systems that worked, institutions that endured, and decisions that could survive contact with reality. In war, that meant logistics, training, and discipline. In peace, it meant food, currency, and confidence. His reputation as the architect of victory in the Second World War rests not on battlefield command but on the quieter, more difficult task of turning a small, unprepared army into a global force capable of fighting on multiple continents at once. His reputation as an architect of peace rests on something even rarer, the willingness to rebuild former enemies rather than punish them for the satisfaction of the moment.

Marshall was born on December 31, 1880, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, a coal town that lived by schedules, shipments, and the hard arithmetic of production. His father, a prosperous coal merchant, believed in order and advancement. His mother believed in character. Marshall later acknowledged that her expectations shaped him more than any lesson he learned in uniform. There was a distant family connection to Chief Justice John Marshall, a lineage his father regarded with pride and George regarded with discomfort. He did not distrust the past, but he did distrust borrowed greatness.

When he enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute in 1897, it was not because he had been groomed for command. It was because he had something to prove. His older brother doubted he could survive the discipline and brutality of the place. VMI was unforgiving, particularly to young men who did not arrive already hardened. Marshall endured relentless hazing, including an episode in which he was forced to squat for hours over a bayonet. He did not complain, and he did not identify those responsible. The incident became part of his reputation, not as a legend but as a marker. He had learned early that authority built on trust lasts longer than authority built on grievance.

He was not a brilliant academic. He was methodical, observant, and relentless about preparation. Military life suited him because it rewarded steadiness rather than flair. By the time he graduated in 1901 as First Captain of the Corps of Cadets, he had already begun to understand leadership as a form of responsibility rather than expression. That understanding never left him.

What The Frock – The Musical

His early Army career offered little glamour. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1902, he was sent to Mindoro Island in the Philippines, where isolation, disease, and logistics mattered far more than tactics. A cholera outbreak forced him to manage frightened troops under conditions that tested patience and clarity. He learned that command was less about issuing orders than about maintaining coherence when circumstances were unpleasant and unchanging. The Army he served in was small, underfunded, and resistant to innovation. Marshall learned how institutions stagnate when they mistake tradition for adequacy.

At Fort Leavenworth, where he attended the Infantry Cavalry School, he encountered ideas that reshaped his thinking. Under Major John F. Morrison, he learned that tactics should be simple and adaptable, not rigid or theatrical. Morrison emphasized understanding terrain, movement, and human limits rather than memorizing prescribed solutions. Marshall finished first in his class, but the ranking mattered less than the habit of thought he absorbed. He carried it with him for the rest of his life.

The First World War was his first encounter with conflict at industrial scale. He arrived in France in 1917 with the 1st Division, among the earliest American units to land. He served as a staff officer, a role that rarely captures public imagination but often determines outcomes. During the Meuse Argonne offensive, Marshall planned the movement of nearly 600,000 troops under cover of darkness, a logistical operation that allowed American forces to surprise the Germans. The feat earned him praise from General John J. Pershing, who recognized in Marshall a rare ability to think clearly amid pressure.

Pershing brought Marshall on as senior aide de camp after the war, a position that exposed him to power at close range. For five years, Marshall observed congressional hearings, diplomatic negotiations, and the uneasy relationship between military necessity and political reality. He later described the experience as essential preparation, a quiet education in how decisions ripple outward beyond their immediate context. It taught him caution, restraint, and the limits of force.

The interwar years were a test of patience. The Army shrank, budgets tightened, and innovation stalled. Marshall refused to coast. His service in China with the 15th Infantry Regiment placed him amid warlord conflicts where restraint mattered more than aggression. He learned basic Mandarin, negotiated tense standoffs, and managed volatility without resorting to force. The lesson stayed with him. Military power, he concluded, was most effective when it did not have to announce itself.

At Fort Benning, as Assistant Commandant of the Infantry School, Marshall staged a quiet revolution. He rejected rigid school solutions and encouraged officers to improvise under realistic conditions. He believed that battle was chaotic and that training should reflect that chaos rather than deny it. Among the officers he mentored were Omar Bradley, J. Lawton Collins, and Joseph Stilwell, men who would later command armies. Marshall remembered competence. He tracked it carefully, not for personal loyalty but for institutional survival.

His work with the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s expanded his understanding of mobilization. Managing large numbers of civilians during economic collapse taught him how morale, dignity, and purpose intersect. He viewed the program as a social experiment in citizenship. When he later raised a citizen army for global war, he already understood how to organize men who had not chosen soldiering as a profession.

On September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, Marshall was sworn in as Army Chief of Staff. The symbolism was grim. The American Army then ranked seventeenth in the world, with barely 174,000 men and outdated equipment. Marshall did not dramatize the situation. He described it accurately. His relationship with President Franklin Roosevelt was professional and deliberate. He insisted on formality, not from arrogance but from necessity. He believed candor required distance.

Before American entry into the war, Marshall confronted Roosevelt over strategic imbalances, particularly the neglect of ground forces. He spoke plainly, risking his career. Roosevelt listened. When war came, Marshall was the man the President trusted to tell him unwelcome truths.

Under Marshall’s direction, the Army expanded to more than eight million men. He reorganized the War Department into Ground, Air, and Supply forces, reducing friction and clarifying command. He removed officers who could not adapt, a process he described privately as clearing deadwood. It was harsh, and it was effective. War did not allow for nostalgia.

Strategically, Marshall advocated relentlessly for a Germany First policy and for a cross channel invasion of France. British leaders preferred peripheral operations in the Mediterranean. Marshall believed delay would cost lives. He pushed for unity of command and global coordination, becoming one of the first American generals to think at truly global scale.

He was widely expected to command the D Day invasion. Roosevelt decided to keep him in Washington, telling him he could not sleep at ease otherwise. Marshall accepted the decision without complaint and recommended Dwight Eisenhower for the role. It was a sacrifice of personal glory that revealed his character more clearly than any battlefield command could have. Winston Churchill later called him the organizer of victory.

After the war, President Truman sent Marshall to China to mediate the civil war between Chiang Kai shek and Mao Zedong. It was an impossible assignment disguised as diplomacy. Marshall achieved a temporary ceasefire and attempted to construct a coalition government. Mutual distrust and ideological rigidity doomed the effort. Marshall returned convinced that the United States should avoid land wars in Asia. It was a conclusion drawn from experience rather than ideology.

As Secretary of State, Marshall confronted a Europe on the brink of collapse. Cities lay in ruins, economies were frozen, and hunger threatened political stability. Communism advanced not through persuasion alone but through desperation. In a commencement address at Harvard in June 1947, Marshall outlined a plan for European recovery. He spoke without notes. He emphasized that the initiative must come from Europe itself and that American aid was directed against hunger, poverty, and chaos rather than any specific nation.

Securing congressional approval required discipline and patience. The program delivered roughly thirteen billion dollars in aid, stabilizing currencies, rebuilding industry, and laying the groundwork for NATO. It transformed former enemies into partners. The alternative, the punitive Morgenthau Plan, would have left Germany resentful and impoverished. Marshall chose reconstruction over revenge.

On the question of recognizing Israel, Marshall advised caution based on strategic concerns. When Truman decided otherwise, Marshall did not undermine him publicly. He believed civilian authority was absolute. That principle would matter again.

In 1950, Truman recalled Marshall as Secretary of Defense during the Korean War crisis. The military had been hollowed out by demobilization. Marshall worked to rebuild capacity while supporting Truman’s decision to relieve General Douglas MacArthur for insubordination. It was unpopular. It was necessary. Civilian control of the military was not negotiable.

In 1953, Marshall received the Nobel Peace Prize, the first professional soldier to do so. The award recognized not idealism but practicality. He accepted it briefly, without flourish. He died in 1959, requesting a simple funeral without eulogy.

Today, his name survives in scholarships and institutions, but his deeper legacy is cultural. Marshall demonstrated that power exercised without ego can shape history more reliably than power advertised loudly. He believed competence was a moral act and that preparation was a form of humility.

President Truman called him the greatest military man this country ever produced. It was not sentiment. It was recognition. Marshall understood that history moves forward not through spectacle but through people willing to build systems, trust subordinates, and accept obscurity when the work demands it. In an age addicted to performance, that lesson remains quietly radical.

Leave a comment