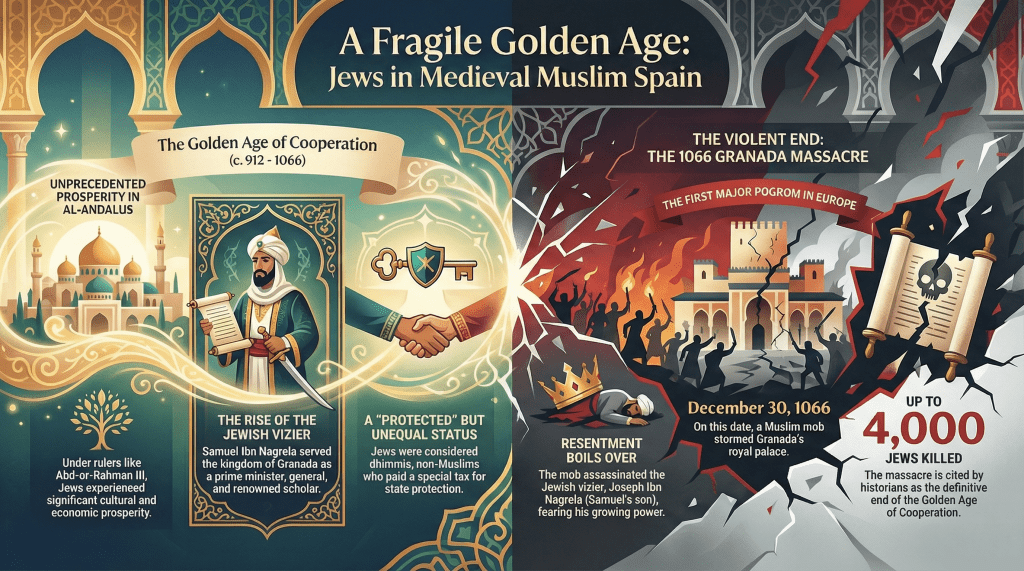

Granada in the winter of 1066 was not supposed to end like this. If you had asked a court poet, a tax collector, or a Jewish merchant counting bolts of cloth in the souk, they would have told you that the age was precarious but workable, dangerous but dazzling. Al-Andalus still wore the reputation of refinement like a borrowed robe, a land where Arabic verse sparkled, Jewish scholarship flourished, and Christian kingdoms loomed at a safe distance, for the moment. The brochures had not yet been printed, but the legend was already forming. A Golden Age, people would later call it, a time of convivencia, the sort of word that sounds better the further away one gets from the blood.

What The Frock – The Musical

To understand how Granada reached that day, one must first let go of the tidy picture. Medieval Spain was not a tolerant paradise that suddenly malfunctioned. It was a fractured, improvisational world held together by personal loyalty, religious hierarchy, and political necessity. When those elements slipped out of alignment, people died. The massacre of 1066 was not random violence. It was the violent resolution of tensions that had been accumulating for decades, waiting for the right spark, the right sermon, the right accusation whispered at court.

The collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba earlier in the eleventh century had shattered any sense of imperial stability. What followed was the fitna, a grinding civil war that left cities burned, dynasties broken, and power scattered among dozens of small taifa kingdoms. Granada became the capital of one such kingdom under the Zirids, Sanhaja Berbers from North Africa who had been soldiers of the old caliphate and then reinvented themselves as kings. They ruled as outsiders in a land dominated by Arabs, local converts, and long memories. That mattered more than later romantics liked to admit.

The Zirid kings needed administrators who could run a state without threatening the throne. Jewish officials fit the requirement neatly. They had education, linguistic skill, and international connections, but no tribal base, no army of cousins waiting in the hills. Their power depended entirely on royal favor. That dependency was the feature, not the flaw. It was how Samuel ibn Naghrela rose to prominence.

Samuel ha-Nagid remains one of the most remarkable figures of medieval Jewish history. Born in Córdoba, trained in Arabic literature and Jewish law, he fled the chaos of civil war and eventually found his way into the service of the Zirid ruler Badis ibn Habus. Samuel did not merely serve as a clerk or tax official. He became vizier, diplomat, and military commander. He led Muslim armies into battle, wrote Hebrew poetry at night, and served as Nagid, the recognized leader of Granada’s Jewish community. No other Jew in the Islamic world held comparable authority for so long.

What made Samuel remarkable was not just his rise, but his restraint. Contemporary accounts describe him as cautious, deferential, acutely aware of how exposed his position was. He cultivated humility as a survival skill. He distributed patronage carefully, avoided ostentation, and understood that envy was more dangerous than incompetence. For nearly thirty years, it worked. Granada prospered, the Jewish community thrived, and Samuel walked a narrow bridge without falling.

His son Joseph inherited the office in 1056 and inherited the bridge with it. He did not inherit his father’s balance.

Joseph ibn Naghrela had grown up surrounded by power, educated in comfort, accustomed to deference. Muslim chroniclers describe him as arrogant and impulsive. Jewish sources are more restrained but do not deny that he lacked his father’s political touch. He favored Jewish allies openly, filled the court with informants, and acted as though royal favor were permanent rather than provisional. Even his residence became a provocation. Joseph built a grand palace overlooking the city, a visible symbol of power that some later traditions associate with the earliest foundations of the Alhambra. Whether or not that claim is archaeologically sound, the symbolism was unmistakable. A Jewish vizier living like a king in a Berber kingdom ruled over Muslims was not merely unpopular. It was theologically combustible.

Islamic law allowed Jews and Christians to live under Muslim rule as dhimmis, protected peoples who paid a special tax and accepted social subordination. The arrangement was pragmatic and, by medieval standards, often workable. It was not egalitarian. Dhimmi status explicitly forbade non-Muslims from exercising authority over Muslims. Samuel’s career had already stretched that principle to its limit, justified by necessity and personal loyalty. Joseph’s behavior snapped it.

Into this volatile mix stepped Abu Ishaq of Elvira, an Arab poet nursing grievances against the Zirid court. Poetry in medieval Al-Andalus was not a parlor game. It was mass media. Abu Ishaq composed a long, scathing poem denouncing Joseph and the Jews of Granada, accusing them of violating their covenant, usurping power, and corrupting the social order. One line survives in multiple sources and deserves to be read slowly: “Do not consider it a breach of faith to kill them. The breach of faith would be to let them carry on.” This was not a call for reform. It was a license for blood.

The poem circulated. Sermons echoed it. Political rivals amplified it. At court, accusations multiplied. Joseph was accused of poisoning the king’s son. He was accused of conspiring with the rival taifa of Almería. Rumors claimed he planned to overthrow Badis and hand Granada to another ruler to save himself. Whether any of this was true is almost beside the point. In a system built on personal trust, suspicion was fatal.

On December 30, the dam broke. A crowd stormed the palace. Joseph tried to hide in a coal pit, blackening his face in a last desperate attempt to escape notice. He was discovered, dragged out, and killed. His body was crucified, a deliberate act of humiliation meant to reverse the hierarchy he had violated. Violence then cascaded outward into the Jewish quarter. This was not targeted assassination. It was collective punishment. Men, women, and children were killed where they lived. Homes were looted. Synagogues were destroyed. By nightfall, Granada’s Jewish community had been effectively annihilated.

Joseph’s wife and son fled to Lucena, one of the few remaining centers of Jewish life in the region. Granada itself would never again host a Jewish community of comparable size or influence. Later rulers permitted limited resettlement, but the spell was broken.

When modern readers encounter the massacre of 1066, there is a temptation to compare it to the Rhineland massacres of 1096 during the First Crusade. The comparison is useful, but only if handled carefully. In the Rhineland, Crusaders driven by apocalyptic fervor attacked Jewish communities with the belief that purging Christ-killers was a prelude to liberating Jerusalem. Jews were often offered conversion or death, leading to episodes of mass suicide sanctified as martyrdom. The violence was theological and eschatological.

Granada was different. This was not holy war. It was a status correction. The Jews of Granada were not killed because they rejected Islam, but because they were perceived to have forgotten their place. The violence was not indiscriminate across religions. Christians were largely untouched. The target was specific, and the rationale was political, legal, and theological in a grimly bureaucratic sense. That distinction matters because it exposes how fragile minority protection was when it rested on custom rather than rights.

Historians have wrestled with this event for generations, often uncomfortably. The idea of convivencia, peaceful coexistence among Jews, Christians, and Muslims in medieval Spain, has been a powerful and appealing narrative, particularly in modern academic and political discourse. It offers a usable past, a counterexample to later expulsions and inquisitions. The massacre of 1066 sits awkwardly in that story. Some treatments minimize it. Others frame it as an aberration.

Revisionist scholars have pushed back, arguing that the so-called Golden Age was neither uniformly golden nor uniquely tolerant. It was contingent, uneven, and punctuated by violence when political balance failed. Primary sources support this view. Abd Allah ibn Buluggin, the last Zirid king, later justified the massacre in his memoirs as a necessary response to Jewish arrogance. This was not the language of betrayal. It was the language of management.

The massacre mattered then, and it matters now, not because it offers a neat moral lesson, but because it exposes how quickly success can become a liability for minorities in hierarchical societies. Samuel ha-Nagid survived because he understood that his power was borrowed. Joseph died because he acted as though it were owned. The system did not forgive that mistake.

After 1066, the political landscape of Iberia grew harsher. The Almoravid and later Almohad invasions imposed stricter interpretations of Islamic law. Jewish communities faced forced conversions, expulsions, and flight. The world that had allowed a Jewish general to command Muslim troops disappeared. It did not vanish because tolerance failed. It vanished because the conditions that made pragmatism profitable no longer existed.

Granada would rise again, crowned with red walls and poetry carved in stone. Tourists would wander its palaces centuries later, imagining a refined past unmarred by screams. The banister still bears fingerprints if one looks closely enough. History rarely erases its own evidence. It simply waits for someone willing to run a hand along the wall and feel where the plaster cracked.

Leave a comment