December 29, 1876, did not begin as a legend. It began as weather, the sort of Lake Erie weather that has always made honest people glance at the window and reconsider their plans. A blizzard rolled in with the hard confidence of something older than railroads, older than schedules, older than the idea that human beings can bargain with nature if they print the timetable in bold type. Snow came in sheets, wind drove it sideways, and the whole landscape around Ashtabula turned into a white blur with sharp edges. The railroad still ran, because that is what railroads did in the nineteenth century. They sold the public speed and certainty, and they sold themselves something even more intoxicating, the belief that steel and ambition could tame the continent.

Train No. 5 of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, the Pacific Express, fought its way east through that storm. On paper it was a first-class service, the kind of train that promised upholstered comfort while the world outside froze. There were parlor cars and sleepers, names that sounded like far off places and gentler nights. There were coal stoves and oil lamps, ordinary conveniences of the era that passengers rarely considered until the moment they became lethal. Inside, people did what travelers always do when forced to wait, they played cards, read, tried to nap, tried to pretend that delay was merely inconvenience and not warning.

It was already well behind schedule as it neared Ashtabula, nearly two hours late by some accounts. That detail matters because storms do not only cover tracks with snow, they cover judgment with impatience. At Erie, Pennsylvania, the railroad added a second locomotive, Socrates, to help push through drifts. The lead engine, Columbia, followed behind. The Pacific Express approached the bridge over the Ashtabula River in the early evening darkness, visibility so poor that a man could barely see more than a car length or two.

What The Frock – The Musical

A bridge is supposed to be the quiet part of the trip. You notice it only when you look down, or when you cross water broad enough to remind you that gravity is not sentimental. Most passengers did not know the name of the bridge they were about to cross, nor the history of arguments, compromises, and arrogance that had been welded into its iron. That ignorance was not their fault. It was a feature of the age. Railroads asked the public to trust them. The public did, because the alternative was to stay home, and America in 1876 was not in the mood to stay home.

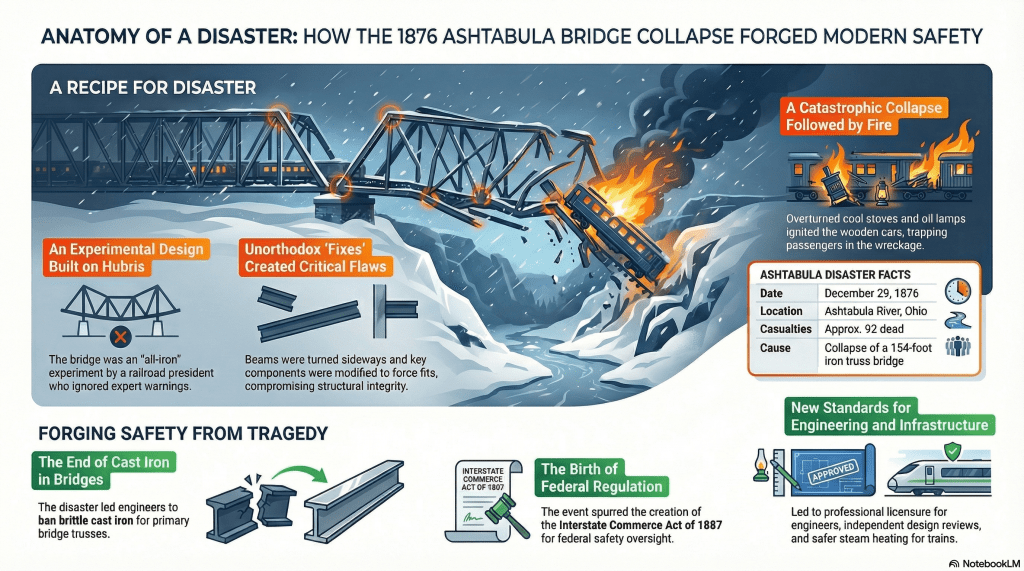

The bridge at Ashtabula was an all-iron Howe truss, a design adapted from a form that had typically combined wood and iron. This one was something different, and the difference was not simply material. It was philosophy. It was the idea that experimentation could be done in public, over a deep gorge, with passenger trains as the test weights.

The driving force behind that experiment was Amasa Stone, president of the railroad and a man with a builder’s confidence. He had been successful, prominent, and accustomed to getting his way. He purchased patent rights associated with the Howe truss and insisted on building the Ashtabula span as an all-iron structure. The trouble was that iron bridges were still developing, the field still learning what stress, fatigue, cold, and time could do to castings and connections. The bridge at Ashtabula was built between 1863 and 1865, and it did not behave like a trustworthy structure even during construction. It buckled under its own weight when the falsework was removed, a moment that should have provoked humility and redesign. Instead, it provoked improvisation.

Joseph Tomlinson, the engineer who drew plans, warned that key members were undersized and the deadload was too great. Stone rejected the warning, and Tomlinson left the project, whether by resignation or dismissal, the record is polite about which. Charles Collins, the chief engineer, was pulled into the mess and then tried to keep distance from it. He later said of the structure, “This is no bridge of mine; that is the President’s bridge.” It is a brutal sentence because it is both accusation and confession. A man does not say that unless he feels the ground shifting under his feet.

The bridge did not have redundancy in the way a cautious designer would prefer. In plain terms, too much depended on too few members doing exactly what they were supposed to do, forever, in all seasons. The coroner’s jury later described the deeper problem with language that still rings true, the “dependence of every member for its efficient action upon the probability that all or nearly all the others would retain their position,” instead of giving each member a positive connection that only direct rupture could sever. That is not merely a technical critique. It is an obituary for a philosophy of design that assumed everything would always go right because it had gone right yesterday.

Even before the catastrophe, there were hints that the bridge was a thing held together by habit and hope. During construction, workers used shims to fill gaps. Lugs on angle blocks were cut away to force parts to fit. Flanges were reduced. Elements were modified in the field as if the bridge were a barn door that could be planed down until it stopped sticking. In an age intoxicated by industry, that kind of rough adjustment was treated as ingenuity. It was really a warning, a crack papered over.

For eleven years trains crossed that span. Each crossing was a small act of faith. Inspectors looked, nodded, moved on, because the bridge had not fallen yet and because the system rewarded speed and punished delay. The coroner’s jury would later point out the simplest condemnation of all, that a careful inspection by a competent bridge engineer over those years could not have failed to discover defects. In other words, the danger was not invisible. It was ignored.

On the night of December 29, the Pacific Express reached the bridge at roughly ten miles per hour, gliding toward the station with steam cut off, the engines coasting in the storm. Engineer Daniel McGuire, on Socrates, felt the bridge begin to surrender. He heard a crack and felt his locomotive drop. He did something that probably saved his own crew and, in a different story, might have saved the whole train. He opened the throttle and surged forward, pulling Socrates toward the abutment as the structure collapsed behind him. The coupling between Socrates and Columbia snapped. Socrates made it to solid ground with the rear of its tender briefly hanging in the air. McGuire stopped down the track and began sounding alarms.

Everything behind him vanished into the gorge.

Columbia and the eleven cars fell roughly seventy feet into the ravine below. The physics of that drop were merciless. Heavy cars crushed lighter ones. Cars telescoped into one another. Wood splintered. Iron couplings snapped like brittle twigs. People were flung against seats, against walls, against strangers. The first moments of survival were not heroic. They were animal. Breath, blood, darkness, the roaring of wind in a place that suddenly felt like the bottom of the world.

Then came the fire.

Passenger cars in 1876 were warmed by coal stoves. They were lit by oil lamps. Those comforts were safe only as long as the car stayed upright and the stove stayed bolted. When the train hit the bottom, stoves toppled and lamps shattered. Flames caught immediately in splintered timber, in upholstery, in the scattered fuel of a luxury train turned into kindling. Survivors described a fire that spread with unnatural speed, fed by wind funneling down the gorge and by the awful fact that so many people were trapped in broken cars that had become cages.

This was where the disaster stopped being about engineering and became about the oldest subject in history, human beings under pressure.

Some passengers freed themselves and crawled out through shattered windows. Some were pinned by wreckage and could not move. Some were alive, conscious, and doomed, forced to listen to the fire coming closer. Accounts from the period dwell on individual horrors, and they do so because that is how people make sense of mass death. A father escaped, heard his child crying out from inside a burning car, and went back. He died there. A woman trapped by her foot begged rescuers to free her before the flames reached her, but the wreckage held her fast. These stories were repeated in newspapers and recollections not because Victorians enjoyed melodrama, but because the mind cannot hold ninety deaths at once without turning them into names and voices.

The town of Ashtabula responded quickly in the way a small town always does when disaster strikes. Men ran toward the gorge. Some came with tools, some with blankets, some with the anxious energy of not knowing what else to do. The gorge itself was a terrible place for a rescue. The access was limited, the stairs down were buried in snow, and the wind made it difficult to see, breathe, or think. The engine house in the ravine, normally just another piece of railroad infrastructure, became the nearest shelter for the injured, the dead, and those trying to decide what was possible.

Fire crews arrived with equipment that should have been useful. What happened next is the part of the story that still makes modern readers stare at the page and ask, how could they let that happen. Witnesses later accused the fire chief, G. A. Knapp, of being intoxicated and indecisive, and of refusing to direct water onto the burning cars. There were also reports of confusion, of volunteers told to stand down, of concern that water would scald survivors trapped inside, concern that had a logic in the abstract but proved catastrophic in practice. While men argued, while authority hesitated, the fire did not hesitate. It consumed car after car until the living who were trapped became silent.

It is tempting to blame one drunk official and move on. It makes the story neat. It also makes it false. The deeper failure was organizational, a town unprepared for a mass casualty event, a railroad unprepared to manage its own wreckage, and a nation that had built a transportation system faster than it had built the institutions needed to police it.

Even in that chaos there were acts worth remembering. A passenger named Marion Shepard reportedly smashed windows to help others escape and then tended the wounded on the ice and snow. Two telegraph operators, John Manning and Charles B. Leek, worked for roughly fifty hours managing the communication storm that followed the weather storm, sending messages for doctors, supplies, and relief trains. Leek in particular matters because he was an African American telegraph operator at a time when that fact alone carried social weight, yet in the crisis his work was simply work, relentless, precise, and necessary. Disaster has a way of revealing what a community really values. On that night, skill and stamina mattered more than prejudice, at least for a little while.

Disaster also reveals the opposite.

Looters descended into the gorge and stripped the dead and dying of watches, money, and jewelry. There is no elegant way to write that. It is ugly because it is true. Later, the mayor issued a proclamation offering amnesty for the return of stolen property. Some items came back. Many did not. A town can be both compassionate and corrupt in the same hour, sometimes in the same person, and Ashtabula was no different. If you want a moral lesson, history refuses. It offers instead a mirror.

Among the passengers were Philip Paul Bliss and his wife Lucy. Bliss was a famous gospel singer and hymn writer, traveling to Chicago for revival work associated with Dwight Moody. In the wreck, Bliss’s body was never conclusively identified. The image of the beloved musician vanishing into fire and snow became one of the story’s enduring notes, a cruel irony that a man known for songs of comfort was swallowed by an event that produced almost none.

In the days after, the scene at Ashtabula became a kind of grim pilgrimage. Families arrived searching for loved ones. Bodies were recovered, carried to temporary morgues, identified when possible. Some were too burned or broken to name. The living wandered with bandaged heads and blistered hands. The town absorbed a wave of grief and shock that its civic life had no practice handling. At the same time the railroad began what large institutions always begin after catastrophe, the management of perception. Statements, explanations, defensiveness, the careful shaping of responsibility into something that could be disputed.

That is where the investigations mattered.

There were three major inquiries, and they were unusually thorough for the time. The coroner’s jury, convened because Ashtabula did not have a coroner, took extensive testimony, including railroad officials and employees, fire department members, passengers, residents, engineers, bridge builders. The jury report, issued in March 1877, did not mince words. It was blunt about design, blunt about construction, blunt about inspection failures.

The language of the verdict reads today like a public ripping of a veil. The jury declared that its conclusions were based on professional evidence and that if the verdict seemed severe, it was because truth demanded severity. Then came the central indictment, a paragraph that should be engraved on the desk of any executive who thinks he can outvote mathematics. The jury stated that Amasa Stone, with the intention of building a safe iron bridge, “designed the structure, dictated the drawing of the plans and the erection of the bridge, without the approval of any competent engineer, and against the protest of the man who made the drawings under Mr. Stone’s direction, assuming the sole and entire responsibility himself.” The verdict called the bridge an experiment that “ought never to have been tried or trusted to span so broad and so deep a chasm,” and said that the cost of that experiment was fearful in human life and suffering.

That is not the language of a minor defect. That is the language of a system failure.

The American Society of Civil Engineers also investigated and produced analysis that helped shift the profession’s standards. One technical detail stands out because it is so painfully mundane. Charles MacDonald identified a flaw in a casting, a void in an angle block that reduced the member’s strength dramatically. In cold conditions, cast iron becomes more brittle, and years of stress can produce fatigue. When that member finally fractured, the bridge’s lack of redundancy meant the failure could cascade with terrifying speed. In modern structural failure studies, Ashtabula is often discussed as a combination of fatigue and brittle fracture at a flaw, a precise engineering description for something that felt, to people in the gorge, like the world simply dropping away.

Charles Collins, the chief engineer who had tried to distance himself from the bridge, was pulled into the public reckoning. In testimony and later reported remarks, he emphasized how little control he felt he had, and how unusual the design was. A man can survive being wrong. It is harder to survive being right too late. Collins broke under the strain. In early February 1877, days after the coroner’s proceedings, he was found dead by gunshot, officially ruled a suicide. The circumstances have fueled speculation ever since. Some have raised questions about the angle of the wound and the absence of powder burns, and there are references to a second autopsy. The honest verdict is that certainty is elusive. People want a clean answer, suicide or murder, because ambiguity is intolerable. History does not always accommodate that need. What can be said without stretching evidence is that Collins was a shattered man caught between professional knowledge and corporate power, and his death became another part of the disaster’s long shadow.

Amasa Stone lived with the disaster longer, and he lived against it. He refused to accept blame, offering alternative explanations like derailment and extreme weather. He may have believed those explanations, or he may have needed them the way a drowning man needs air. In 1883, facing business troubles and the lasting stain of Ashtabula, Stone took his own life. It is not a satisfying ending. It is not justice. It is simply the last act of a story built on pride.

For the rest of the country, Ashtabula did something that tragedies sometimes do. It forced the living to change how they built.

In bridge engineering, cast iron became suspect for critical truss members. Professional standards shifted toward stronger materials and clearer design practice. Discussions that would influence later specifications, including the move toward more rigorous design guidance, drew energy from disasters like this one. The idea that a railroad president could dictate a major structural design without independent competent review began to look less like bold leadership and more like negligence written in advance.

Ashtabula also fed the growing appetite for government oversight. Before this era, the United States had a curious habit of treating mass death as a private matter unless it happened in a battlefield. As one contemporary commentary put it, America had “hardly any where” adequate provision for inquiry beyond “the clumsy machinery of a coroner’s jury,” even though “in four cases out of five someone is responsible,” through carelessness, false economy, defective discipline, or ignored safety measures. Those lines were not written by modern regulators. They were written by nineteenth century observers already tired of watching corporations kill people and call it misfortune.

The specific regulatory path from Ashtabula to later federal action is not a single straight line, but the general arc is clear. Public pressure, repeated disasters, and professional advocacy pushed the country toward stronger oversight of railroads, culminating in major federal interventions in the 1880s, including the Interstate Commerce Act. Americans did not wake up one morning and decide to regulate. They were pushed there by wreckage.

There were local changes too, quieter but no less important. Ashtabula had no proper hospital capable of handling mass casualties. The disaster exposed that gap brutally, and the town’s medical infrastructure changed in the years that followed. If you want to understand how communities modernize, do not look only at speeches and laws. Look at where they build their hospitals, and why.

Passenger safety practices also evolved. Coal stoves inside wooden cars were a known hazard, tolerated because they were convenient and because catastrophe had not yet forced the issue. After Ashtabula and other fires, the movement toward safer heating systems gained urgency. Again, progress arrived late, but it arrived.

The dead at Ashtabula were buried in a way that reveals another truth about disaster. In the first days, names mattered. Families searched, identified, claimed remains. Later, unclaimed bodies and unidentifiable fragments became a communal responsibility. A mass grave at Chestnut Grove Cemetery held those who could not be named. There is something sobering about that, the way individuality survives for a time and then yields to necessity. It is not cruel. It is simply how communities endure.

It is also how memory fades.

Ashtabula was, by most counts, the deadliest railroad disaster in the United States in the nineteenth century, and it remained a benchmark of horror until the early twentieth century brought even larger catastrophes. In its own day, it was national news, a symbol of modernity’s dark underside. Over time it became local history, then niche history, then the kind of thing you stumble upon in an old book and wonder why you never learned it in school.

There is a reason for that forgetting. Rail disasters are unsettling because they reveal how much of modern life depends on trust in systems we do not see. A bridge is a promise. A timetable is a promise. An inspection report is a promise. When those promises are broken, people do not merely die. Confidence dies too. That is why corporations rush to control the story, why officials find convenient villains, why the public sometimes prefers weather to blame, because weather has no board of directors.

Ashtabula does not let that escape route stand unchallenged. The coroner’s jury told the country, in plain language, that the bridge was an experiment, that it lacked competent approval, that defects were discoverable, that inspection failed. This was not fate. It was choice.

It is easy to read that and nod along with modern superiority. We have codes now, standards, software, professional licensure, safety culture posters taped to the break room wall. Then a bridge fails today, or a platform collapses, or an industrial system breaks and people die, and the language in the reports starts to sound familiar, cost cutting, ignored warnings, overconfidence, organizational confusion, the refusal to treat safety as the first obligation rather than an optional expense. The century changes. The temptations do not.

Ashtabula is not a story about how terrible the past was and how enlightened the present is. It is a story about a permanent human weakness, the urge to gamble with other people’s lives when there is money on the line and accountability feels distant. The jurors in 1877 saw that clearly. They described Stone’s confidence, his belief that the bridge would be the crowning glory of an active life and an enduring monument to his name. That is a striking phrase, not because it is poetic, but because it is so recognizably human. People want monuments. They want legacy. They do not want to be told that legacy can become a grave.

If there is a closing image worth keeping, it is not the fall itself, though the fall was terrible. It is the gorge afterward, wind still howling, snow still coming, the burned timbers cooling into black ribs, the town above stunned into silence. It is the telegraph key clicking through the night under the hands of exhausted operators. It is the makeshift morgue, the families arriving with hope they cannot justify. It is the mass grave for those who never got their names back. It is also, uncomfortable as it is to admit, the small crowd of looters moving among the dead, proving that even in a blizzard, some people can still find a way to be cold.

History has a way of leaving fingerprints on the banister, and Ashtabula left many. Some were iron filings and ash. Some were ink in a coroner’s verdict written by men determined, at least for one moment, to tell the truth without flinching. The lesson is not neat. It never is. The past does not hand out moral slogans like souvenir spoons. It offers instead a hard, old-fashioned warning: progress is not the same thing as wisdom, and confidence is not the same thing as strength.

If you listen closely, you can still hear that warning under the wind off of Lake Erie, not as poetry, not as sermon, but as the plain sound of a bridge that should never have been trusted, giving way.

Leave a comment