The morning of December 26, 1825 (O.S.), opened in St. Petersburg the way Russian winter mornings often do, with cold that does not so much bite as settle in and refuse to leave. Senate Square lay hard and white under the sky, the Neva locked beneath ice thick enough to bear cannon and men, or so it seemed until it did not. By midmorning, roughly three thousand soldiers stood assembled in a rigid square, boots planted, muskets idle, breath hanging like unspoken questions. They were members of the Life Guards, the sort of men raised to obey without hesitation, yet here they were refusing an oath. Not to God. Not to Russia. But to a new emperor whose legitimacy had become suddenly uncertain. In that hesitation, in that pause long enough for frost to creep into fingers and resolve, the first Russian revolution revealed itself, not as a roar, but as a held breath.

What gathered that day was not a peasant riot or a drunken mutiny. It was something stranger and far more dangerous to an autocratic state. The men behind it were officers, many of them aristocrats, veterans of foreign campaigns, readers of banned books, men who had seen Paris and Vienna and Berlin and returned home unsettled by what they had learned. They did not rise because they were starving. They rose because they were thinking. That distinction mattered then, and it matters now.

What The Frock – The Musical

Russia in 1825 was a paradox built on muscle and fear. It had defeated Napoleon and marched its armies into the heart of Europe, yet it remained governed by an absolute monarch ruling over millions of legally enslaved peasants. The men who stood on Senate Square had helped save the empire in 1812 and had watched their peasant soldiers fight, bleed, and die for a country that denied them legal personhood. That contradiction did not sit easily with officers who had walked the boulevards of Paris and seen constitutional governments function, imperfectly but visibly. They returned home carrying more than medals. They carried comparison, which is always the most subversive luggage.

This revolt failed, and it failed quickly. It lacked coordination, popular support, and decisive leadership at the moment when those things mattered most. Yet it also succeeded in ways that were not immediately visible. It fractured the bond between the throne and the educated nobility. It terrified the new emperor into building a police state. It created a mythology of sacrifice that would echo through Russian culture for a century. In that sense, the Decembrists lost the battle on the ice of the Neva, but they changed the weather.

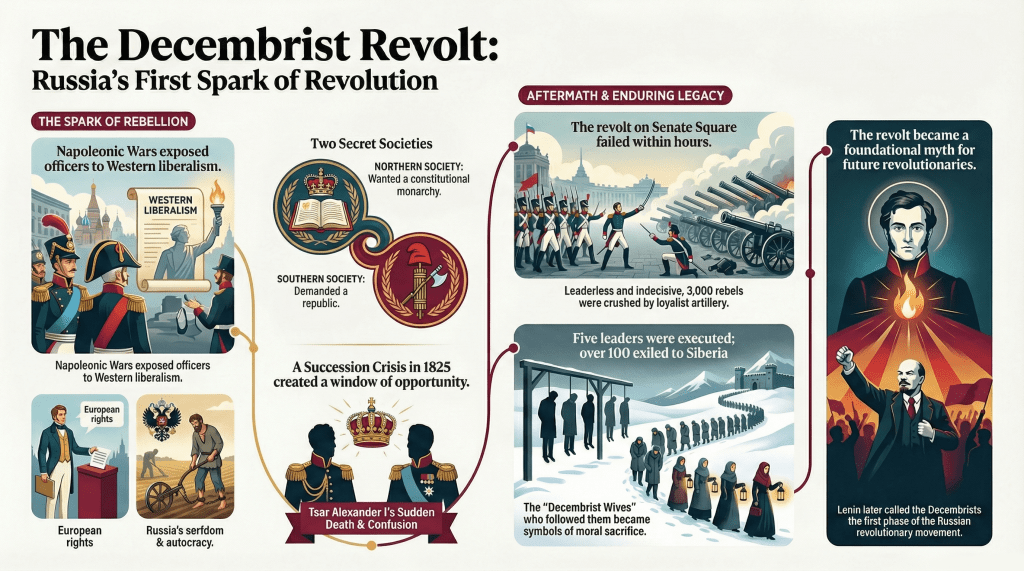

The intellectual roots of the movement lay in the generation sometimes called the Children of 1812. These were young noblemen who had come of age during the war against Napoleon and the long pursuit of the French armies across Europe. In those years, Russian officers lived among Europeans who argued openly about rights and constitutions, who spoke of citizenship as something other than a favor granted by a monarch. The exposure was not abstract. It was lived experience. Officers attended salons, read pamphlets, listened to debates, and returned to Russia aware that alternatives existed.

Their disappointment was sharpened by the figure of the emperor himself. Alexander I had ascended the throne with liberal promise. Early in his reign, he spoke of reform and flirted with constitutional ideas. Some of his advisers dreamed openly of gradual emancipation and legal restraint on autocratic power. Then came the shock of the Napoleonic Wars and the exhaustion that followed victory. After 1815, Alexander turned inward, toward mysticism and reaction, toward the Holy Alliance and a vague belief that order was preferable to liberty, especially if liberty came with risk. The emperor who granted constitutions to Poland and Finland denied one to Russia itself. That decision stung. It felt personal.

Out of that disappointment grew secret societies, the sort of thing governments always imagine are more organized and dangerous than they really are. The Union of Salvation formed in 1816, a small circle of officers who believed Russia could and should be governed by law rather than whim. Among them were members of the Muravyov family, Prince Sergei Trubetskoy, and the intense, driven Pavel Pestel. Their aims varied, but they shared a conviction that serfdom was a moral abomination and that unchecked autocracy was unsustainable.

The Union of Welfare followed, larger and more diffuse, borrowing its language from moral improvement societies in Prussia. It talked of education and virtue, of gradual change, of making Russia better by making Russians better. That sort of talk always sounds safer than it is. By 1821, internal divisions and fear of discovery led to its dissolution. What emerged instead were two distinct organizations with sharply different visions for Russia, the Northern Society in St. Petersburg and the Southern Society in Ukraine.

The Northern Society was cautious, legalistic, and, in its own way, aristocratic even in rebellion. Led by figures like Nikita Muravyov and the poet Kondraty Ryleev, it imagined a constitutional monarchy with a written constitution, a bicameral legislature, and voting rights limited by property. Muravyov’s draft constitution abolished serfdom but allowed landlords to retain most land, granting peasants only modest plots. It was reform from above, careful, measured, and deeply concerned with order.

The Southern Society was something else entirely. Under the leadership of Colonel Pavel Pestel, it embraced a radical republicanism inspired by the Jacobins of the French Revolution. Pestel’s manifesto, Russkaya Pravda, called for the abolition of the monarchy, the execution of the imperial family, and the creation of a centralized republic. His agrarian program proposed dividing land into public and private spheres, ensuring peasants access to subsistence while preserving some private ownership. It was uncompromising, ideological, and frightening to anyone who believed revolutions should behave politely.

These differences mattered, because revolutions tend to fail when their participants cannot agree on what victory would look like. They mattered even more when history presented an unexpected opening.

That opening came with the death of Alexander I in November 1825. He died suddenly in Taganrog, far from the capital, leaving behind a succession problem that would have been farcical if it had not been so dangerous. The legal heir was Grand Duke Constantine, Alexander’s older brother, but Constantine had secretly renounced the throne two years earlier to marry a Polish commoner. Alexander had signed a secret manifesto naming his younger brother Nicholas as successor, but the document was not made public. When news of the emperor’s death reached St. Petersburg, Nicholas himself swore allegiance to Constantine, unwilling to appear a usurper.

Constantine refused to come to the capital or issue a public abdication. Weeks passed. Russia had two emperors and none at all. For the conspirators, this confusion was opportunity. They spread rumors among the troops that Nicholas was seizing power illegally, that Constantine was being held against his will. When Nicholas finally resolved to assume the throne and ordered a new oath of allegiance on December 14, the Decembrists moved.

The plan was bold and disastrously dependent on men behaving as planned. Rebel units would refuse the oath, march to Senate Square, seize the Winter Palace, arrest the royal family, and force the Senate to proclaim a provisional government. Prince Sergei Trubetskoy was appointed dictator of the uprising, a title that sounded impressive and proved meaningless.

When the moment came, Trubetskoy did not. Overcome by nerves or fear or sudden clarity, he failed to appear. Other key figures hesitated or withdrew. The result was paralysis. Thousands of soldiers stood for hours without orders, while officers argued quietly and time slipped away.

Nicholas I, newly emperor and acutely aware that this was his first test, hesitated as well. He did not want bloodshed to mark his accession. He sent emissaries, including the respected war hero Mikhail Miloradovich, to reason with the troops. It was a fatal gesture. Miloradovich was shot by the radical Pyotr Kakhovsky, a moment that shattered any remaining chance of compromise.

Cavalry charges failed on the icy square. The light was fading. Crowds were gathering, throwing stones, testing the edges of order. Nicholas made the decision every autocrat eventually makes when faced with uncertainty. He ordered artillery to fire. Canister shot tore into the formation. Soldiers fled toward the frozen Neva, where the ice broke under the weight of men and fear. By nightfall, the revolt in St. Petersburg was over.

In the south, events unfolded with a grim echo. Pestel was arrested before news of the northern failure even arrived, betrayed by informants. His followers in the Chernigov Regiment rose anyway under Sergei Muravyov Apostol, marching through Ukraine with proclamations framed as Orthodox catechism. They were defeated by artillery fire in early January 1826. The revolution ended not with a bang, but with paperwork.

The investigation that followed was personal. Nicholas interrogated prisoners himself, reading confessions, weighing motives, absorbing the depth of dissent within his officer corps. He emerged convinced that the threat was not isolated but systemic. One hundred twenty one men were sentenced. Five were condemned to death, including Pestel and Ryleev. Their execution was botched, the ropes breaking and the men hanged again. Russia, like all empires, was never very good at symbolism on the first try.

More than a hundred others were stripped of rank and sent to Siberia for hard labor and exile. It was meant to be erasure. Instead, it became legend.

Perhaps the most enduring human story of the Decembrist revolt belongs not to the men who stood on Senate Square, but to the women who followed them east. Eleven noblewomen chose to accompany their husbands into exile, surrendering titles, wealth, and legal rights. Nicholas attempted to deter them by forbidding them to bring their children, forcing a choice between marital duty and motherhood. Some left children behind. Some never returned.

In Siberia, these women lived in peasant huts near prisons, worked with their hands, wrote letters for men forbidden to correspond, and created a fragile domestic world amid punishment. Their sacrifice was romanticized by poets and absorbed into Russian culture as proof that moral authority could exist outside the state. It was a story the empire could not control.

Nicholas responded to the revolt by hardening everything. He created the Third Section, a secret police tasked with monitoring thought itself. He embraced an official ideology of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, a defensive creed meant to smother liberal ideas. In doing so, he ensured that dissent would become quieter, deeper, and more determined.

Ironically, the exiled Decembrists transformed Siberia. They introduced schools, medical care, agricultural innovation. They became cultural leaders in a place meant to erase them. The state punished them, and they improved what it had neglected. History is full of such unintended consequences.

The legacy of the Decembrists is complicated, which is the only honest way history ever is. They were aristocrats who spoke of liberty while commanding serfs. They were idealists who failed to understand the people in whose name they claimed to act. Lenin later dismissed them as being terribly far from the people, even as he credited them with awakening a revolutionary tradition. The Soviets canonized them while ignoring how alien their liberal constitutionalism would have been to Bolshevik rule.

What matters is not that they were right or wrong in some abstract sense. What matters is that they broke the silence. They demonstrated that the autocracy was not inevitable, that obedience could fracture, that ideas could cross borders and return home changed. The first attempt failed catastrophically. It also ensured there would be a second, and a third.

On that frozen square in December 1825, Russia learned something about itself. It learned that loyalty could hesitate, that obedience could pause long enough for thought to intrude. The ice broke, men drowned, and the empire survived. It survived, but it was never again quite as certain of itself.

Leave a comment