Victory or Death was not poetry. It was not rhetoric. It was not a line meant for a broadside or a crowd. It was a password, chosen carefully, whispered in the dark on Christmas night in 1776, and it told the truth with an honesty that few slogans ever manage. The men who carried it did not expect comfort, applause, or even survival. They expected a fight they could not afford to lose, because there was nothing left to retreat into. On the west bank of the Delaware River, ice grinding against ice, the American Revolution stood on a narrow margin between endurance and extinction.

The river that night was not the romantic barrier later paintings would make of it. It was black, swollen, and angry, clogged with jagged slabs of ice that struck the hulls of the boats like blunt weapons. Snow had not yet fully claimed the evening, but sleet and freezing rain soaked wool coats, stiffened fingers, and turned every task into a negotiation with pain. Men bled from their feet. Some had wrapped rags around shoes that had already surrendered weeks earlier. Others had nothing between their soles and the frozen ground except stubbornness. This was the army that would cross the river, not to win glory, but to stay alive.

The idea that this was merely a daring raid misses the point. The crossing of the Delaware was a strategic pivot, not because it destroyed a garrison, but because it arrested a collapse already in motion. By December of 1776 the American rebellion was failing in plain sight. What followed on Christmas night did not guarantee independence. It did something more basic and more necessary. It kept the war from ending.

What The Frock – The Musical

The road to that riverbank was paved with failure. The New York campaign earlier that year had been a slow unspooling of hopes. The defeat on Long Island had been decisive and humiliating. White Plains followed with no redemption. Fort Washington fell in November, nearly three thousand men lost in a single blow, along with cannon, muskets, and supplies the army could not replace. Fort Lee was abandoned soon after, its stores left behind in a retreat that bordered on flight. What remained of the Continental Army dissolved backward across New Jersey, pursued relentlessly by British columns that seemed to move at will.

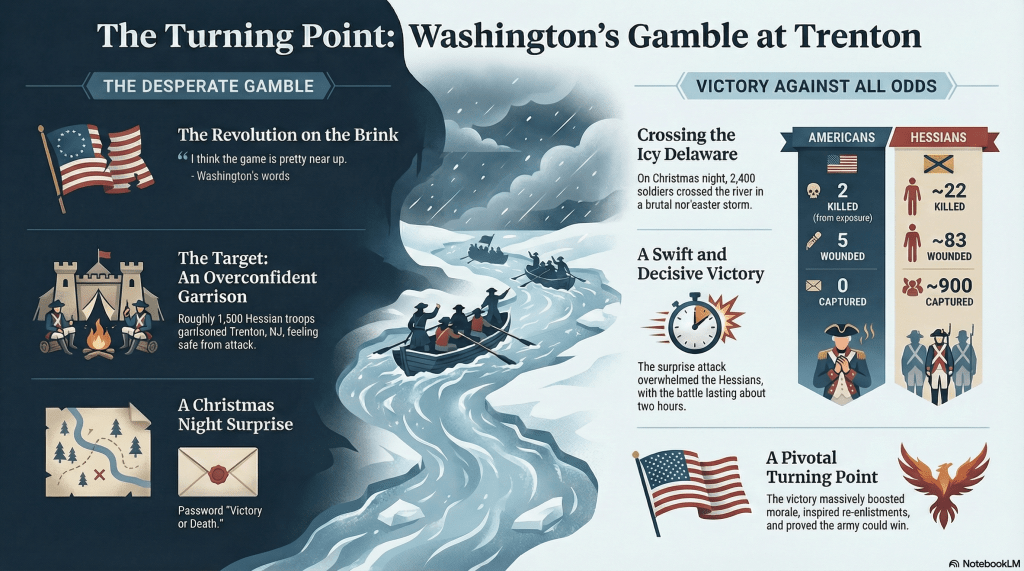

George Washington understood what was happening, and worse, he understood what it looked like. Soldiers deserted in steady trickles. Enlistments expired as December wound down, with most set to end on the last day of the year. The Continental Congress, reading the same reports and drawing the same conclusions, fled Philadelphia for Baltimore. The rebellion, once loud with declarations and confidence, had begun to speak in whispers. In a private letter to his brother, Washington admitted what he would never say aloud to his men. He believed the game was nearly up.

The British saw it too, and they believed it. William Howe chose not to press the advantage to its conclusion. He dispersed his forces into winter cantonments across New Jersey, stretching from New Brunswick to Trenton and Bordentown. It was a reasonable decision. Armies traditionally rested in winter. Roads turned to mud, rivers froze, supply lines thinned. The rebellion, in British eyes, had been broken sufficiently. Time and weather would finish the job. There was no urgency left in it.

Washington did not have that luxury. A Fabian strategy of retreat and delay had reached its limit. There was no more room to give. If the army went into winter quarters on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware without a victory, it would not come out again in the spring. The men would go home. The cause would become a memory. Washington needed a blow that could be felt immediately, not only by the enemy, but by his own soldiers, by wavering civilians, and by foreign observers who were quietly keeping score.

That was where words mattered. Thomas Paine had published The American Crisis only days earlier, opening with lines that refused comfort and offered clarity instead. Washington ordered it read aloud to the troops. It did not promise ease. It promised meaning. It framed endurance as a test of character rather than a sentence of misery. The men listened because the words matched their circumstances. Anything else would have sounded false.

Across the river, in Trenton, Colonel Johann Rall commanded the Hessian garrison. Rall was not a fool, and he was not drunk, despite a myth that refuses to die. His men were experienced soldiers, worn down by constant militia harassment that allowed no rest and no sense of safety. Pickets fired at shadows. Alarms rang for nothing. Sleep came in fragments. Rall believed, with some justification, that the Americans lacked the strength and nerve to mount a serious winter attack. He also refused repeated orders to fortify the town properly, dismissing earthworks as unnecessary against what he regarded as country rabble. It was not arrogance so much as professional habit. He had seen irregular forces before. He believed he understood them.

Washington’s plan was bold, complicated, and fragile. It depended on coordination in conditions that mocked coordination. Three columns would cross the Delaware on Christmas night. Washington himself would cross at McConkey’s Ferry with the main force and march directly on Trenton. General James Ewing would cross south of the town to block escape across the Assunpink Creek. Colonel John Cadwalader would cross farther downstream to threaten Bordentown and distract British reinforcements. If all went well, the Hessian garrison would be isolated, surprised, and overwhelmed before it could react.

Nothing went entirely well. The boats mattered more than the plan, and the right boats mattered most of all. The Durham boats were workhorses of commerce, long and black hulled, designed to haul iron ore. Their high sides and shallow draft made them stable in rough water and forgiving in ice. They were not elegant, but they were indispensable. Equally indispensable were the men who knew how to handle them. Colonel John Glover’s Marblehead Regiment, sailors and fishermen from Massachusetts, including free Black men, took the oars and poles. They worked in darkness and freezing spray, guiding overloaded boats through a river that wanted to break them apart.

Henry Knox, massive, tireless, and loud enough to be heard above wind and water, coordinated the movement of artillery. Eighteen guns had to cross, each a problem unto itself. Horses slipped. Wheels jammed. Orders were shouted and repeated. It was not smooth. It was relentless.

The weather worsened as the night wore on. Rain turned to sleet, sleet to snow. Ice thickened and shifted. The crossing that should have been completed by midnight dragged on into the early hours of the morning. By three o’clock the artillery was finally across. Ewing and Cadwalader had failed to cross at all, blocked by ice and forced to abandon their attempts. Washington stood on the New Jersey shore with roughly 2,400 men, hours behind schedule, daylight approaching, and no supporting columns. Retreat across the river under those conditions was impossible. Delay meant discovery. There was only one choice left, and he made it.

The march to Trenton was nine miles of misery. Snow blinded men already exhausted. Wind cut through wet clothing. Some marched in silence. Others muttered prayers or curses. Blood marked the road where bare feet met frozen ground. At one point General John Sullivan reported that the men’s powder was wet and their muskets unreliable. Washington’s reply was simple. They would use the bayonet. It was not bravado. It was instruction.

The army divided as planned, Greene’s column approaching from the north with Washington present, Sullivan’s from the west. Hessian pickets fired and fell back, surprised but not yet panicked. The sound of artillery rolling into position at the head of King and Queen Streets changed that. Alexander Hamilton directed the guns with precision, turning the narrow streets into channels of destruction. Hessian formations broke under the fire. Rall attempted to rally his men, to form for a counterattack, but the town itself worked against him. Confusion replaced coordination. Orders collided. Units stumbled into each other.

James Monroe was wounded leading a charge to capture enemy cannon. Rall himself was mortally wounded as he tried to organize a defense outside the town. Within ninety minutes the fight was over. Nearly nine hundred Hessians were captured, along with artillery, muskets, and supplies the Continental Army desperately needed. American losses in battle were astonishingly light. Two men had died of exposure during the march. Five were wounded in combat. It was not a miracle. It was preparation meeting opportunity under extreme pressure.

The return crossing was almost as difficult as the first. Prisoners had to be guarded. Captured equipment had to be ferried back. The weather did not improve out of courtesy. Ice still ruled the river. Yet by nightfall the army was back in Pennsylvania, alive, victorious, and transformed in ways that would take time to register.

Washington did not waste that time. With enlistments expiring on December thirty first, he gathered the men and asked them to stay six more weeks. He offered ten dollars as a bounty, paid from his own funds. It was not generosity alone. It was necessity. Enough men agreed to keep the army intact. Days later Washington crossed the Delaware again, reentering New Jersey to confront Cornwallis. What followed were the Ten Crucial Days, a running campaign that included the stand at the Assunpink Creek on January second and the stunning night march to Princeton, where another British force was defeated on January third. By the time the army settled into winter quarters at Morristown, the rebellion was no longer collapsing. It was breathing.

The effects rippled outward. Morale surged, not into triumphalism, but into something sturdier. Men reenlisted. Militias stirred. Civilians who had hedged their bets began to lean back toward the cause. Abroad, observers took notice. France had been watching carefully, skeptical of American durability. Victories like Trenton and Princeton did not secure an alliance on their own, but they changed the conversation. They suggested competence. They suggested resilience. They suggested that this was not a rebellion that would fold at the first hard winter.

In Britain the shock was real. The assumption that the war was winding down gave way to the realization that it had merely changed shape. Support wavered. Confidence thinned. The war would go on, longer and costlier than anticipated. Frederick the Great would later call Washington’s winter campaign one of the most brilliant in military history, not because it was flawless, but because it was necessary and executed under conditions that punished every mistake.

The image that endures is Emanuel Leutze’s painting, Washington standing tall in a boat that never existed, under a flag not yet adopted, crossing a river in daylight that had been crossed in darkness. It is wrong in its details and right in its meaning. The crossing was not about elegance. It was about resolve carried by ordinary men, including sailors, laborers, farmers, immigrants, and free Black Americans, moving together across a barrier that did not care whether they succeeded.

The crossing of the Delaware matters because it reminds us that history often turns not on grand inevitabilities, but on moments when failure seems more likely than success, and action is taken anyway. It was not clean. It was not glorious in the moment. It was cold, dangerous, and frightening. Without it, the Declaration of Independence would likely have ended as a brave document attached to a brief and unsuccessful revolt.

Victory or Death was not a promise. It was an admission. On that river, on that night, the American Revolution chose to continue.

Leave a comment