Every December, as the year limps toward the wall and the ledger books begin to close, we reach for A Christmas Carol the way a tired hand reaches for a familiar coat. We know how it feels. We know how it ends. We know which emotional notes will be struck and when. It reassures us that people can change, that cruelty is curable, that goodness wins if given one well-timed supernatural shove. It is comforting, efficient, and deeply familiar.

On this December 23 Christmas Eve Eve episode of Dave Does History on Bill Mick Live, Dave Bowman asks an uncomfortable question that most seasonal retellings carefully avoid. What if that comfort is not the point. What if Dickens was not trying to tuck us in at all.

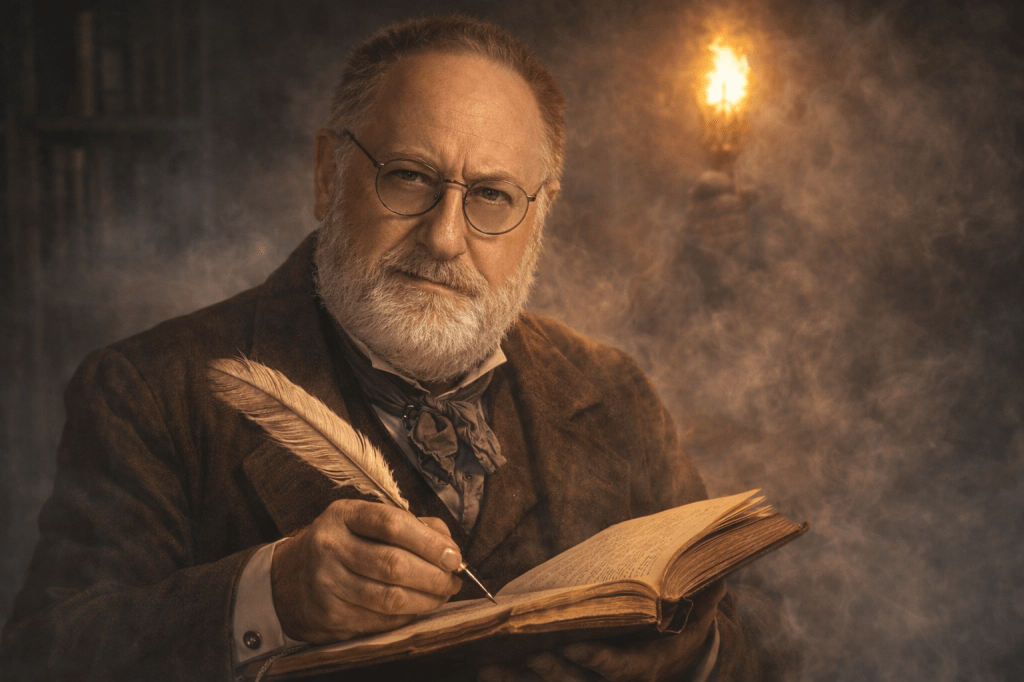

Rather than treating A Christmas Carol as a sentimental holiday relic, Dave reintroduces Charles Dickens as what he actually was in 1843, a furious social critic with a reporter’s eye and a growing impatience for a society that had learned how to explain away suffering with respectable language. Dickens was not writing from nostalgia. He was writing from exposure. He had already attacked the workhouse system in Oliver Twist. He had already forced England to look at itself and flinch away. The Carol was not a retreat from that fight. It was a refinement of it.

What The Frock – The Musical

The episode dismantles the idea of Scrooge as a cartoon villain. Scrooge is lawful. He is rational. He follows the rules. He believes what English society already believes. When he asks about prisons, workhouses, and treadmills, he is not inventing cruelty. He is reciting policy. Dickens places those words in Scrooge’s mouth because they were already on the lips of respectable people across Victorian England. The horror of the scene is not that Scrooge hates people. It is that he sounds reasonable.

Dave traces how the New Poor Law, Malthusian ideas, and bureaucratic indifference combined to create a system that punished poverty while congratulating itself for doing so. Treadmills existed not to produce anything useful, but to keep the poor moving, out of sight, and out of mind. Motion was mistaken for morality. Suffering was renamed discipline. Dickens knew exactly what he was indicting.

The ghosts, in this telling, are not magical fixes. They are moral instruments. They expose. They accuse. They do not excuse. The children revealed beneath the Ghost of Christmas Present’s robe, Ignorance and Want, are not sentimental symbols. They are warnings. Dickens makes it clear which one will destroy society first, and it is not hunger. It is willful blindness.

Perhaps the sharpest turn in the episode comes when Dave asks what happens after the book closes. Scrooge changes. England largely does not. We celebrate redemption while ignoring the conditions that made it necessary. We applaud the ending and return to dinner. Dickens, Dave argues, intended the story to linger, to haunt, to demand something after the applause fades.

The episode closes by pulling the question forward into the present. Laws that criminalize homelessness. Systems that hide need rather than address it. The temptation to confuse order with justice. The reminder that “mankind was my business” is not a comforting line but a demanding one.

This is not an episode about ruining Christmas. It is about remembering what Dickens was actually trying to do. You may never see A Christmas Carol the same way again.

Leave a comment