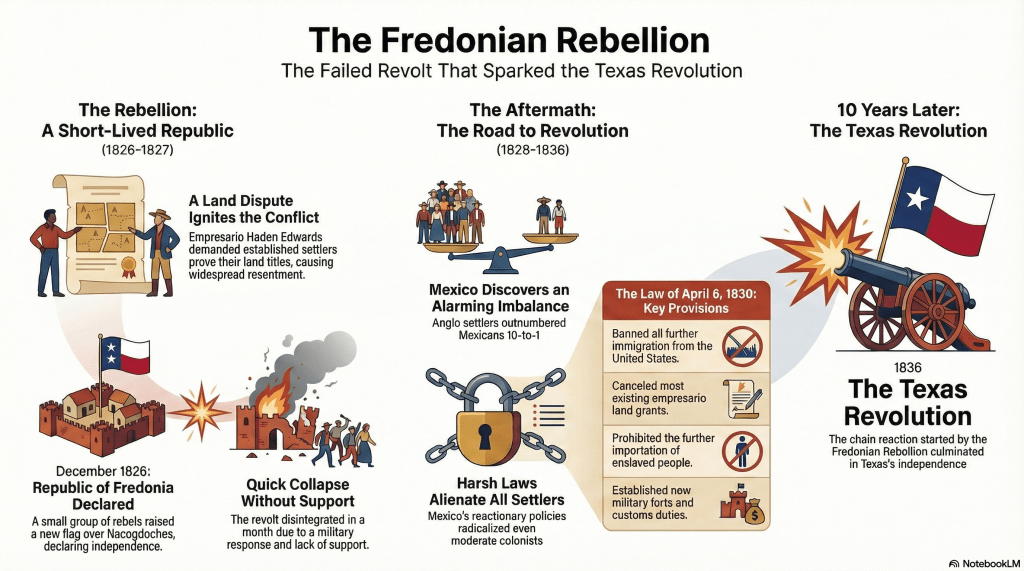

On the morning of December 21, 1826, a flag went up over the Old Fort at Nacogdoches. It was red over white, roughly made, stitched by hands more accustomed to frontier repairs than nation building. It did not rise to the sound of drums or cannon. It was hauled up on a wooden pole by men who looked over their shoulders as often as they looked at their handiwork. Beneath it stood a small crowd, some curious, some committed, most uncertain. The flag announced the birth of the Republic of Fredonia.

The republic would not survive the winter. It would barely survive the month. No decisive battle would be fought in its name. No foreign power would recognize it. Its founders would flee rather than fall. And yet, this brief and awkward uprising would matter far more than its size suggested. Fredonia did not change Texas because it succeeded. It changed Texas because it frightened the Mexican government into seeing the future too clearly and responding too harshly.

What The Frock – The Musical

To understand why that flag mattered, it helps to step back into a Texas that did not yet think of itself as Texan.

Mexican Texas in the 1820s was not a place of clean maps and firm authority. It was a borderland inherited by a young nation still trying to decide what kind of country it intended to be. Mexico had won its independence from Spain only a few years earlier. Its treasury was thin, its institutions fragile, and its northern frontier stretched far beyond the reach of reliable enforcement. Texas, vast and underpopulated, posed both an opportunity and a danger.

The solution adopted by Mexico seemed sensible enough. Encourage settlement. Invite families from the United States to move south, swear allegiance to Mexico, convert to Catholicism, and act as a buffer against Native resistance and American expansion. This policy became law under the colonization acts of 1823 and 1825, which formalized the empresario system. Empresarios were contractors of sorts, granted the authority to recruit settlers, distribute land, and administer local affairs under Mexican oversight.

On paper, it was orderly. In practice, it landed atop a frontier already layered with unresolved claims.

Nacogdoches was not an empty town waiting for improvement. It was one of the oldest European settlements in Texas, a place where Spanish, Mexican, Native, and Anglo worlds overlapped uneasily. Some families traced their land claims back generations, through handwritten grants issued under Spanish rule. Others held Mexican titles of varying clarity. Cherokee communities lived nearby, displaced from the United States but not fully anchored in Mexican law. The Neutral Ground along the Sabine River added another element, a lawless strip that attracted fugitives, smugglers, and men who preferred ambiguity to authority.

Into this delicate environment came Haden Edwards.

In April of 1825, Edwards received a contract to settle 800 families in East Texas. He arrived in Nacogdoches that September carrying legal authority and a temperament poorly suited to negotiation. Almost immediately, he posted notices requiring all existing landowners to present proof of title or forfeit their land. It was a move grounded in law but blind to reality. Verified grants were rare. Records were scattered. Many residents had lived on their land for decades without formal paperwork.

Edwards did not bend. He did not delay. He did not listen.

What followed was predictable. Old settlers, some of whom had endured Spanish rule, Mexican transition, and frontier hardship, now found themselves threatened by a newcomer with papers and power. They did not see order. They saw dispossession. Edwards quickly became a unifying force, not because he inspired loyalty, but because nearly everyone disliked him.

The conflict soon turned political. In 1825, an election was held for alcalde, a position that combined judicial and administrative authority. Edwards backed his son in law, Chichester Chaplin. The old settlers rallied behind Samuel Norris. Chaplin claimed victory. Norris’s supporters alleged fraud, pointing out that unqualified voters had participated and that Edwards himself had certified the result.

Mexico intervened in March of 1826. Political chief José Antonio Saucedo overturned the election and installed Norris. Edwards refused to accept the decision. He continued to behave as though Chaplin held office. By doing so, he crossed a line. The dispute was no longer local. It was a direct challenge to Mexican authority.

The response came in mid 1826. Citing Edwards’s oppressive conduct, the Mexican government annulled his contract. For Edwards, the decision was catastrophic. He estimated his losses at fifty thousand dollars, a staggering sum on the frontier. More damaging than the money was the implication. Mexico had sided with the old settlers. Edwards saw not justice, but betrayal.

At that moment, Edwards made the decision that would define him. Rather than retreat, appeal, or rebuild elsewhere, he chose defiance. If Mexico would not protect his investment, he would separate from Mexico entirely.

The insurrection did not begin with grand declarations. It began with force. In November of 1826, Martin Parmer, John S. Roberts, and Burrell J. Thompson led thirty six armed men into Nacogdoches. They arrested Samuel Norris and José Antonio Sepulveda, accusing them of oppression and corruption. A theatrical trial followed. Joseph Durst was installed as alcalde. Authority shifted hands, at least temporarily.

On December 21, the rebels formalized their break. At the Old Stone Fort, they signed a Declaration of Independence. The document accused the Mexican government of faithlessness and despotism, claiming that settlers had been reduced to the dreadful alternative of either submitting their free born necks to the yoke or taking up arms. The language echoed earlier revolutions, as if legitimacy might be borrowed through familiarity.

They named their creation the Republic of Fredonia, a term drawn more from classical imagination than geographic sense. Haden Edwards and his brother Benjamin envisioned a government modeled loosely on American republican forms, with themselves at its center. What they lacked was support.

That lack drove them toward their most consequential decision. They sought an alliance with the Cherokee.

The Cherokee leaders Richard Fields and John Dunn Hunter had grievances of their own. Promised land titles by Mexican authorities, they had received little more than delay and uncertainty. They lived in a precarious space, unwanted by the United States, under acknowledged but inconsistent Mexican protection. An alliance with Edwards offered recognition and land in writing.

The Treaty of Union, League and Confederation divided Texas between Red people and White people, drawing a line roughly from Nacogdoches to the Rio Grande. It was bold. It was unprecedented. It was also deeply alarming. To Mexican officials, it suggested not merely rebellion, but fragmentation. To Anglo settlers, it threatened instability. To Stephen F. Austin, it looked like madness.

Austin responded immediately. He believed in peace and loyalty, not out of sentimentality, but strategy. He condemned the rebellion and mobilized his colony’s militia in support of the Mexican government. In a letter to Burrell J. Thompson, Austin urged restraint, warning that the uprising would bring consequences far worse than Edwards imagined.

Mexico responded militarily. Lieutenant Colonel Mateo Ahumada departed San Antonio with 110 infantrymen and 20 dragoons. But the decisive turn came not from soldiers, but diplomacy. Mexican Indian agent Peter Ellis Bean, working alongside Austin, persuaded the Cherokee leadership to abandon the alliance. The message was clear. Mexico would not tolerate a separate Indian state carved out of Texas. Continued cooperation with Edwards would invite destruction.

The Cherokee withdrew. Richard Fields and John Dunn Hunter were executed by their own people for their involvement. It was a brutal end that underscored how thoroughly Fredonia had misjudged its position.

By January 31, 1827, the rebellion was over. The Edwards brothers and their followers fled across the Sabine River into the United States. The Republic of Fredonia collapsed without a battle, without martyrs, and without much sympathy.

Mexico did not relax. It hardened.

The immediate aftermath saw increased military presence across Texas. While some conspirators were captured, mass executions did not follow. What did follow was distrust. Mexico no longer viewed Anglo settlers as invited colonists. It began to see them as a demographic threat.

That fear led directly to the inspection of Texas by General Manuel de Mier y Terán in 1828. His report was blunt. Anglo settlers outnumbered Mexicans ten to one in East Texas. American influence was overwhelming. Mexican sovereignty was dangerously weak. He warned that Texas could throw the whole nation into revolution.

Mexico listened.

The Law of April 6, 1830 followed. Immigration from the United States was banned. Empresario contracts were suspended. The importation of enslaved people was prohibited. New forts and customs houses were established to enforce federal authority.

The law did what Fredonia never could. It alienated the moderate majority.

Settlers who had opposed Edwards now found themselves restricted and suspected. Loyalty no longer offered protection. Radical voices gained credibility not because they were persuasive, but because moderation seemed futile.

Fredonia did not cause the Texas Revolution directly. What it caused was fear. Fear led to overreaction. Overreaction led to resistance. Resistance eventually led to war.

Haden Edwards failed. But his failure mattered. He raised a flag that should not have mattered, in a place that barely noticed, at a moment when Mexico could least afford complacency. The republic vanished. The consequences did not.

Sometimes history turns not on triumph, but on the sound of something small breaking at exactly the wrong moment.

Leave a comment