There are moments in history when nations behave a little like anxious teenagers, glancing sideways at a rival and doing whatever it takes to avoid looking weak. The United States found itself in exactly that position in late 1961. The Soviets were streaking ahead in the space race with a confidence that bordered on smug. Yuri Gagarin had already taken his victory lap around the Earth, and Gherman Titov had stayed aloft long enough to make it look routine. Meanwhile the United States had managed two short suborbital hops, brave and important in their own way, but hard to compare to the orbital achievements of the other side. Americans understood perfectly well that they were behind, and they did not like it. The pressure on NASA was immense. Some in government wanted to send an astronaut into orbit immediately. The feeling in the air was that the country needed to show it could keep up, even if it meant cutting a few corners and hoping for the best.

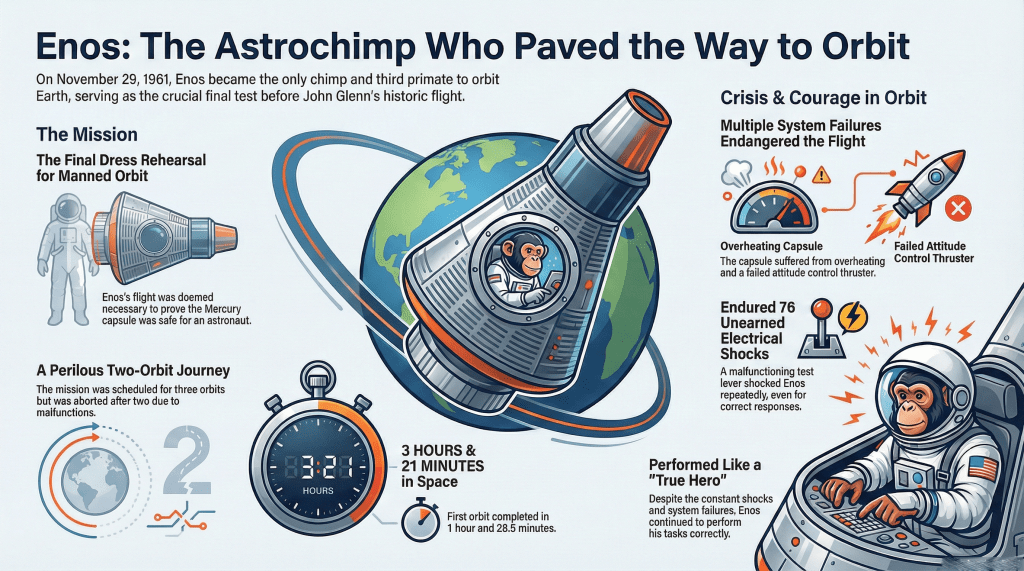

NASA did not like cutting corners, and engineers tried their best to explain that orbital flight was a different beast than a short ballistic arc. There were practical questions that had not been answered about the hardware, the reentry heating, the guidance systems, and even the human mind itself. These questions were not political. They were biological and technical. They needed data before they put a man into that capsule. So NASA did what NASA did best in those early days. It built a mission to gather the facts. The mission that emerged was Mercury Atlas 5, scheduled for November 29, 1961, and the passenger chosen for it was a five year old chimpanzee, born in Cameroon and given the Hebrew name Enos, meaning man. The symbolism was hard to miss. Before a human astronaut could trust the machine, Enos would have to go first.

Enos was not a performer. He did not have Ham’s public charm or the easy confidence of a natural mascot. Those who trained him described him as clever, watchful, and anything but cuddly. If you leaned in too close, he might bite you. He was not hostile by nature, just unwilling to pretend he liked you. The trainers respected him because he was bright, quick to learn, and capable of staying calm in an environment built to make even a seasoned pilot sweat. Enos completed more than twelve hundred hours of training at the University of Kentucky and at Holloman Air Force Base. His regimen was tougher than Ham’s because the mission would last for several hours, not a quick up and down. He had to endure prolonged weightlessness, higher G forces, and the kind of noise and vibration that made Mercury capsules feel like tin cans strapped to the front end of a very angry rocket.

The training included a series of psychomotor tasks that measured his cognitive performance. He learned to press one of three levers that corresponded to a pattern of shapes. When he chose correctly, he received a small reward of banana pellets or water. When he chose incorrectly, he received a brief electric shock to the soles of his feet. The early space program was not built around gentle teaching methods. It did not pretend it was sending animals into a pleasant experience. Life was hard and experimental science can be harder. Enos learned the task so well that he became reliable under stress, which was the whole point. NASA needed to know whether a living, thinking being could remain functional during the punishing phases of orbital flight. Everything depended on that answer.

The hardware was undergoing its own version of the training grind. Mercury Capsule Number Nine was a Mark II model with the larger square window that astronauts liked because it gave them a real view outside, not a cramped porthole. The capsule had an explosive bolt hatch, the same type that would later contribute to an accident involving Gus Grissom, although no one was thinking about that yet. The heat shield had been designed to survive the friction of orbital reentry, which was far more intense than the suborbital descents of Shepard and Grissom. The booster for the mission was the Atlas LV 3B, a machine that engineers both admired and feared. The Atlas had a complicated personality. It was thin skinned, famously delicate, and prone to vibration problems. For this flight the autopilot had been adjusted after earlier flights revealed vibration levels that no one wanted to see repeated. NASA needed a smoother ride, at least smooth enough that a chimpanzee could function inside a pressurized chamber the size of a small closet.

The hours leading up to launch felt longer than they needed to be. Enos was inserted into the capsule inside his own customized primate couch roughly ninety minutes before the launch window opened. The countdown stalled and restarted several times. Weather was fine, but the rocket and the ground equipment both demanded attention in that way that only early space hardware can demand it. Launch crews at Cape Canaveral treated the Atlas with a mix of respect and suspicion. You did not trust an Atlas until it left the pad and even then you watched it like a man watching a suspicious neighbor carry something heavy out to the curb at two in the morning.

When the countdown finally reached zero, the booster lifted from Launch Complex 14 at 15:07:57 UTC. The engines burned with enough force to pin Enos to his couch with G forces approaching eight times the weight of his body. A human pilot might have used a few choice words to describe that sensation. Enos had no such luxury. He had to ride it out. The Atlas behaved better than expected. The modified autopilot kept the rocket from shaking itself to pieces. Within a few minutes the capsule separated, the boosters fell away, and Enos found himself in an elliptical orbit that carried him 158 kilometers above the Earth at its highest point and 237 kilometers at its lowest. The numbers were everything NASA wanted to see. Enos had become the third primate in history to orbit the planet, and by far the least celebrated.

The first orbit went well. The capsule assumed its planned attitude and consumed only a modest amount of fuel to maintain position. Enos performed his lever tasks with precision. He seemed comfortable enough in the weightless environment, at least as far as anyone could tell from the telemetry. The engineers in Mission Control relaxed a bit. They watched the data scroll across the screens in the Mercury Control Center. The flight director, Christopher Kraft, took in the numbers and allowed himself the smallest measure of relief. The ship was flying clean. The chimp was doing his job. The universe seemed to be cooperating, at least for that first hour and a half.

The trouble began during the second orbit. It started with the kind of technical glitch that always looks small on paper but grows into something serious when a spacecraft is traveling thousands of miles an hour far above the ocean. A metal chip in a fuel supply line jammed one of the clockwise roll thrusters. The automatic control system sensed the misalignment and tried to compensate by firing other thrusters. This worked for a moment, then began to spiral into overcorrection. The thrusters that did work had to burn more fuel to fight the drift caused by the thruster that did not. Fuel consumption surged. A mission that had started with a comfortable reserve suddenly found itself gulping control gas at an alarming rate. The astronauts who would later ride those Mercury capsules liked to say that fuel was life. Once you ran out of attitude control fuel, you stopped being a pilot and became a passenger on a very unpredictable ride.

That was bad enough, but the capsule also began to report rising temperatures in parts of the environmental control system. Instrument data showed that the couch suit circuit was heating up in a way that suggested the heat exchanger might be freezing. There were strange artifacts in the readings for the inverter. The engineers began to worry that the electrical system might follow the attitude control system into partial failure. Enos’s body temperature climbed to levels that suggested he was under significant stress. Spaceflight is not kind on a good day. On a malfunctioning day it can become cruel.

Then the psychomotor task system malfunctioned. One of the levers began shocking Enos even when he selected the correct response. A chimpanzee may not understand systems analysis, but he understands a punishment he did not earn. During two separate task sessions, Enos endured more than seventy unintended electrical shocks. He continued to perform the task correctly, which revealed something about his intelligence and temperament. Somewhere inside that frightened and frustrated animal, a kind of instinctive discipline held firm. He did what he had been taught to do, even as the system punished him for behaving correctly. There is a strange dignity in that. It is the dignity of any creature that continues the work in front of it even when the world is painful and makes no sense.

NASA had planned to run the mission for three full orbits. That idea evaporated quickly once the attitude control system began consuming fuel at a rate that resembled a leak. The mission controllers knew they could keep the capsule in stable orientation for a while longer, but not for another entire orbit. The rising temperatures inside the environmental control system added another layer of risk. The flight director made the call. The capsule would terminate after the second orbit. It was a difficult decision, but not a complicated one. Bring Enos home while you still can.

The order was transmitted. The retro rockets fired. The capsule began its long fall back toward the atmosphere. Reentry for Enos was largely uneventful, which is not the same as comfortable. Even on a good day, Mercury reentry felt like tumbling through fire inside a metal drum. The heat shield performed exactly as designed. The spacecraft survived the peak heating phase and slowed into the dense air of the lower atmosphere. Parachutes deployed. The seas rose to meet the capsule.

Splashdown occurred at 18:28:56 UTC in the Atlantic Ocean, around two hundred miles south of Bermuda. The total mission time was a little over three hours and twenty minutes. The ocean was not rough, but the recovery was slow. Enos sat in that capsule for more than three hours waiting for the recovery ship, USS Stormes, to arrive. The sun dropped lower. The waves thumped gently against the metal hull. Enos waited.

When the recovery crew finally reached the capsule, they tested the explosive bolt hatch by pulling the external lanyard. The hatch blew off with a sharp crack that fractured the capsule’s picture window. The crew did not care about the window. They wanted to know how the passenger looked. Enos looked angry and exhausted. He had torn apart his medical garment and removed his catheter himself, which probably hurt like fury. He was alive, physically stable, and very much done with the experience. He was transported to the Air Force hospital in Bermuda and then flown to Cape Canaveral on December 1. He survived the mission with no lasting injury, at least none that could be observed.

The post flight data told a complicated story. The mission had achieved its two major objectives. It had tested the environmental control system under realistic orbital conditions, and it had validated the procedures required to recover a capsule from orbit. Those were the minimum goals required before NASA would trust the machine to carry a human astronaut. The data also revealed that the capsule could maintain reentry integrity under real world stresses. The heat shield worked. The capsule survived the process of heating and deceleration as expected. This gave engineers a measure of confidence that no atmospheric test chamber could match.

The technical failures that plagued the flight turned out to offer something valuable. The investigators concluded that the thruster malfunction and the overheating inverter would likely have been manageable if a human astronaut had been aboard. A human pilot could have disconnected the faulty automatic system, realigned the capsule manually, and even worked around the electrical issues by following emergency checklists that no chimpanzee could understand. In other words, the mission proved that the machine was ready but also that a human was essential. It was no longer a theoretical point. It was data.

Enos returned to Holloman after the mission. He received modest attention, far less than Ham had received after his suborbital flight. Enos had done something more technically complex, yet he never became a public figure. The public did not rally around the chimp that suffered through a malfunctioning experiment and a heat stressed capsule. They were focused on the next milestone. John Glenn would soon make history, and Enos became a footnote to the main event. The country was grateful, but not sentimental. The space program was moving too fast for that.

He died less than a year later, on November 4, 1962, from dysentery caused by shigellosis, a disease resistant to the available antibiotics. The veterinarians who examined him reported that his death showed no sign of being related to the stresses of spaceflight. He had been a healthy animal in the months following his return. The disease struck quickly and did not respond to treatment. There is something quietly tragic about that. After surviving a violent ride to space and back, he succumbed to a microbial enemy that humans have been wrestling with for most of recorded history.

Today Enos is rarely mentioned in discussions of the early space program. Ham gets the press. Glenn gets the glory. Gagarin gets the first place ribbon. Enos occupies a strange middle space, not forgotten by historians yet seldom acknowledged by the broader public. His capsule was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1967 and remains in the national collection. Enos’s couch is displayed at the Cosmosphere in Kansas. Visitors walk past it without always understanding the story behind it. It looks like a peculiar chair from a lost era, which is exactly what it is.

The meaning of Enos’s flight grows clearer with distance. His mission served as a bridge between the suborbital experiments and the moment when a human being risked his life on Atlas and Mercury. That bridge had to be sturdy. It had to show not only that the systems could function, but also that they could fail without killing the occupant. Enos endured malfunctions that revealed weaknesses in the automated systems. He endured the shocks, the heat, the drift, and the long wait on the ocean. He held up his end of the work. The engineers held up theirs. The combination was enough to send John Glenn into orbit three months later.

There is a quiet lesson in that story. It is not a moral lesson and not a modern political analog. It is simply the reminder that progress often requires someone or something to go first and absorb the uncertainties. Enos did not choose his role. He had no way of knowing that he was flying into a contest between two superpowers or into a milestone that would eventually lead to Neil Armstrong stepping onto the Moon. He was doing what he had been trained to do. He was responding to patterns, enduring discomfort, and performing tasks that made sense only to the humans watching the data.

When the United States declared that the Mercury Atlas 5 mission had paved the way for John Glenn, it was not exaggerating. Enos’s flight removed the final doubts that NASA had about the hardware. It solidified the belief that the capsule and Atlas booster could carry a human into orbit. It also showed that human intervention was not optional. It was essential. The failures that occurred on that second orbit were proof that the machine needed a thinking pilot. Glenn became that pilot. The country gained its first orbital success. Enos faded into the background.

Yet the deeper truth is that progress builds on such quiet stories. Enos rode a rocket that no one trusted completely and behaved with more discipline than anyone had reason to expect. He proved that a living being could function inside that violent, unforgiving environment. He made the unknown slightly less unknown. When Glenn climbed into his capsule on February 20, 1962, he was entering a vehicle that had already been tested under real world orbital conditions by a small, serious chimp who had done everything asked of him.

Enos never saw the celebration that followed Glenn’s flight. He never saw the parades or the newspaper headlines. He never heard the applause. His story sits in the archives, waiting for anyone curious enough to turn the pages. When you read those pages, you start to understand why the early space race felt so desperate and so determined. You also start to see the strange companionship between the human desire for knowledge and the willingness to place another creature into harm’s way to gain it. It is not always comfortable history. It is real history.

There is something both humble and heroic in Enos’s brief presence in the firmament. He orbited the Earth twice and returned home alive. He did not understand the significance of what he had done, but the engineers understood it very well. His mission succeeded because he endured discomfort, stayed on task, and provided the data that the nation needed. That is not a glamorous legacy. It is a necessary one.

History is built of such necessities. They are not clean. They are not sentimental. They carry a weight that settles on the reader long after the page is turned. Enos the Chimp flew into that weight and gave NASA the confidence to place an astronaut into orbit. His contribution sits there in the margins, quiet and irreplaceable. If you walk through a museum someday and see a strange looking couch behind glass, stop for a moment and give it a second look. That couch carried a reluctant pioneer who helped humanity take another step away from the Earth and into the empty sky.

Leave a comment