Artemas Ward is one of those figures who sits quietly at the edge of the American Revolution, the way a man might stand just outside the light of a campfire. People know Washington. Some know Knox. A few know Putnam. Ward, if remembered at all, is too often mistaken for a vaudeville comedian who came along a century later. It is the sort of historical injustice that makes you shake your head. Here was the man who commanded the provincial army that surrounded Boston before Washington ever arrived. Here was the man the Continental Congress came close to elevating as the first official Commander in Chief. John Adams admired him so deeply that he called Ward universally esteemed, beloved and confided in by his army and his country. Yet to this day historians bury him in a footnote. Ward did not chase glory. He quietly held the line and built the army Washington needed, then watched other men take the bows. History likes its heroes bold and brash. It rarely holds the same affection for the organizers and caretakers of a fragile cause. Ward built the scaffolding that kept the Revolution from collapsing before it even started.

His story matters because he stands in the small but important space between chaos and direction. He was the transition point from a spontaneous uprising to a national war effort. He did not dazzle. He steadied. And if you want to understand how the Revolution survived those early fragile months, you start with the man in Shrewsbury who carried the weight before Washington ever set foot in Cambridge. Ward’s life is full of lessons, some whispered from the Puritan past, others hammered by the failures of British leadership, and many taught by the simple fact that revolutions need quieter hands holding the edges while louder hands swing the sword. His story is deeper than the textbooks ever bother to tell, because they rarely mention just how close he came to being remembered as the commander whose name we all know. That did not happen. But understanding why tells you something about New England, about Congress, about Washington, and about the long, stubborn American habit of forgetting the people who did the slow, grinding work.

He began his life in Shrewsbury on November 26, 1727, born into a family planted deep in New England soil. Nahum and Martha Ward raised their sixth child in the sturdy expectation that he would serve his community. Shrewsbury was still young, a place that needed farmers, judges, surveyors, and leaders, often all at once. Ward was shaped by that world, a place where responsibility passed from parent to child as naturally as seed to furrow. His education followed the usual path of the well placed provincial families, beginning in the common schools and continuing under private tutors. He moved on to Harvard, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1748 and a master’s in 1751. Harvard still carried the scent of Puritan discipline in those days. Ward even volunteered to help crack down on swearing among the students. It seems like a small detail, but it reveals the strict sense of personal duty that would shape him for the rest of his life.

He married Sarah Trowbridge in 1750 and settled into the life of a gentleman farmer. Ward’s rise in local affairs was almost immediate. He held a remarkable number of public offices for such a young man, serving as Justice of the Peace, a town representative, and a steady participant in the political life of Worcester County. New England politics in that era rewarded quiet reliability more than fiery rhetoric, and Ward, with his disciplined habits and conservative approach, fit naturally into that world. Farmers knew him. Townsmen trusted him. When trouble came, the people of Shrewsbury already knew who they wanted handling important matters.

His first taste of real war arrived in 1755 during the French and Indian conflict. Ward joined the militia as a major, and by 1758 he had risen to lieutenant colonel in the provincial forces. These were hard years for New England soldiers, who repeatedly suffered from British blunders. The worst was the 1758 assault on Fort Ticonderoga, also known as the Battle of Carillon. British generals, convinced that sheer force could overcome French entrenchments, ordered frontal assaults against fortified positions without waiting for artillery support. The result was a bloodbath of more than two thousand casualties. Ward was spared the carnage only because he was bedridden with what he called an attack of the stones, meaning bladder stones. But he watched the consequences of that disaster unfold. Men he knew never came home. The lesson was sharp. Recklessness in battle kills unnecessarily. Caution is not cowardice. War rewards preparation more than bravado.

Those principles stayed with him for the rest of his military life. If you want to understand Ward’s caution in the Revolution, you look back to Ticonderoga. He had seen what happens when commanders ignore the terrain, the conditions, and the limits of their own forces. The future general of the Massachusetts army learned these lessons early, and they carried into every decision he made in the years ahead.

After the war, Ward returned to the political arena. He became a judge of the Court of Common Pleas in 1762, where he quickly positioned himself at odds with royal authority. The British Parliament began tightening the screws on the colonies through taxes and trade restrictions. Ward did not take kindly to such pressures. He opposed the new taxes openly, plainly, and consistently. He was that rare figure who felt no need to shout his resistance. His principled stance nevertheless made him an unmistakable obstacle to the Crown’s policies.

Royal Governor Francis Bernard noticed. In 1767 he revoked Ward’s militia commission as a punishment for his growing political defiance. It did nothing to slow him. Ward continued his rise, elected repeatedly to the Governor’s Council, though Bernard vetoed his appointment each time. The people of Massachusetts wanted Ward standing between them and royal overreach. The governor wanted him gone. The conflict only raised Ward’s stature among Patriots.

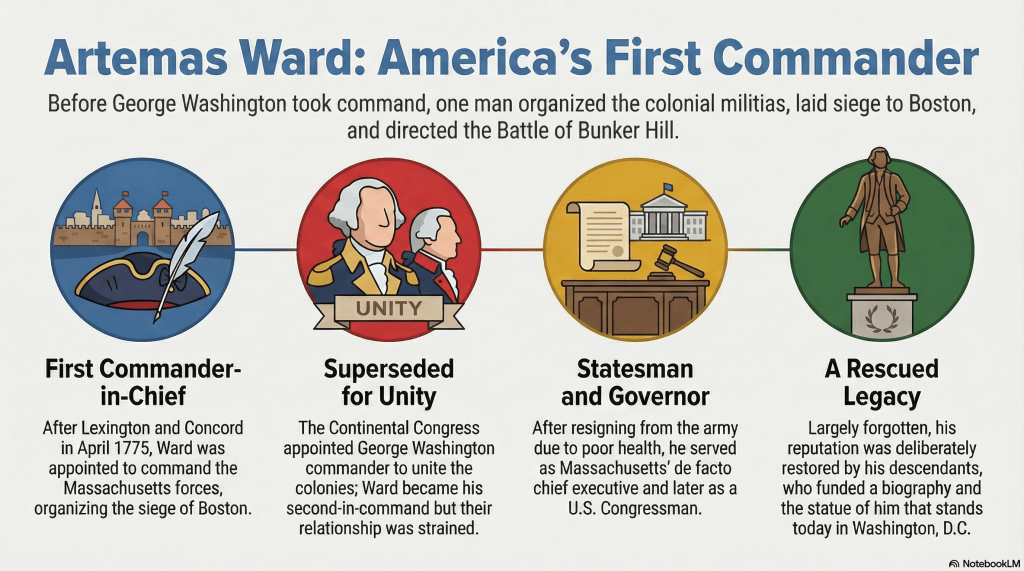

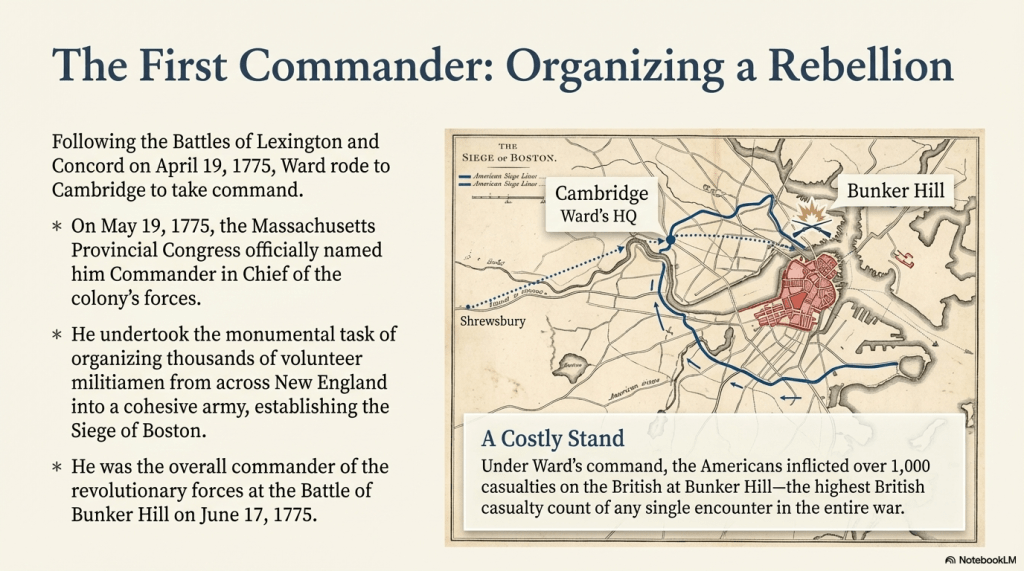

By 1774 the air around Boston crackled with tension. Ward pushed the Provincial Congress to secure arms and supplies, understanding that conflict was no longer an if but a when. On October 27, 1774, the Congress appointed him a brigadier general. He did not have to wait long to take the field. The shooting at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, turned everything from protest into open war. When Ward heard the news, he mounted his horse and rode to Cambridge, arriving on April 20 to take command of the provincial militia that had converged on Boston.

This was the moment that tested everything he had learned. He walked into a makeshift army that had swelled almost overnight. The men were volunteers. Their officers were often elected by their own troops. They were brave but undisciplined, determined but scattered. They came not just from Massachusetts but also from New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. They all needed leadership, structure, and supplies. Ward was the man responsible for giving them an army that could hold a siege.

He established headquarters in Cambridge and organized the first council of war. Then he set about the monumental task of turning this mob of determined citizens into a functioning fighting force. Ward handled enlistments, supply shortages, and command disputes. He managed raids into Boston Harbor and kept the lines around the besieged city intact. His abilities showed most clearly in this period. He was an organizer at heart, steady, methodical, and focused on creating stability.

But those same strengths revealed his weaknesses. Ward preferred consensus among his officers. He hesitated to enforce discipline. He knew that the men fighting around Boston believed they were defending their own homes and communities, not serving in the professional ranks of a European style army. To impose harsh discipline would have meant alienating them. Ward tried to steer between firmness and patience. Sometimes he succeeded. Sometimes he frustrated those who wanted a more forceful hand.

By May 20, 1775, Ward had taken the oath as commander in chief of the Patriot army. He was now officially in charge of the entire effort in Massachusetts. That made him the man responsible for the coming crisis on the Charlestown peninsula, where the British prepared to break the siege.

The Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, remains one of the most famous engagements of the Revolution, though it was fought mostly on nearby Breed’s Hill. Ward was the overall commander. When he learned the British planned to seize the heights, he ordered the Americans to fortify Bunker Hill. The officers on the ground chose Breed’s Hill for reasons of elevation and cover, but the command came from Ward. The battle itself became a brutal, close range fight. The Americans inflicted heavy casualties before finally being driven off for lack of ammunition.

Criticism rose almost immediately. Some complained that Ward had been slow to send reinforcements. Others argued that he should have personally gone to Charlestown instead of staying at Cambridge, where he was worried about the southern defensive lines at Roxbury. James Warren and others turned their grievances into loud accusations. But many of the attacks came from political maneuvering in Massachusetts, where rivalries ran deep. Ward kept the siege intact even after the Americans lost the hill, a fact that tends to get lost in the retelling. Still, the criticism stuck, the way mud tends to stick even to men who do their duty as best they can.

As Congress met in Philadelphia, the question of who should command the new Continental Army loomed large. Ward had a strong base of support. By some accounts the greatest number of delegates initially favored him. But Congress needed unity. They needed the South as invested in the war as New England. So they made the political choice. George Washington of Virginia became Commander in Chief. Ward accepted the decision and officially handed command to Washington on July 7, 1775.

Ward did not fade into the background. Congress commissioned him a major general on June 17, 1775, making him second only to Washington. Their relationship, however, was strained from the start. Ward never warmed to Washington. Washington, who preferred swift action and strong discipline, found Ward too cautious. Ward disliked what he saw as remarks injurious to his reputation. Neither man ever said much in public about the tension, but it simmered all the same.

Conflict aside, Ward continued to serve. He commanded the right wing of the army and helped plot the strategy for the Siege of Boston. Here his earlier lessons proved invaluable. Ward argued strongly for the importance of Dorchester Heights, the commanding ground overlooking the city. Once Knox hauled the cannon from Fort Ticonderoga, Ward’s sector became the stage for the decisive move. In March 1776 American forces fortified the heights. The British had no answer. They pulled out of Boston soon after. Ward’s caution turned into victory. He had waited for the right moment. When it came, he helped deliver the first major triumph of the Revolution.

Exhaustion and illness finally took their toll. Ward submitted a resignation in March 1776, blaming the chronic agony of his bladder stones. Washington persuaded him to stay on a little longer, and he agreed to oversee the defense of New England. He remained in command of the Eastern Department until March 1777, when he retired from the army for good. By then the war had moved south and west. Ward took on different duties.

He stepped immediately back into Massachusetts politics. From 1777 to 1779 he served as President of the Executive Council and President of the Massachusetts Senate. In effect he was acting as the state’s chief executive during a crucial phase of the war before Massachusetts adopted a new constitution. Ward became a cornerstone of order and continuity at a time when the state needed stability.

He returned to the Massachusetts House of Representatives several times, becoming Speaker in 1786 during the crisis of Shays’ Rebellion. When the rebels marched on the Worcester courthouse, Ward stood firm. He faced them down, insisting that the law would hold. It was a dangerous moment in a fragile new republic. Ward’s quiet strength mattered more than flashy speeches or fiery oaths. He kept the peace as best he could and held faith in the rule of law.

Ward later served as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1780 and 1781. Then he moved on to federal service as a Federalist representative in Congress from 1791 to 1795. His most notable act in the House was his vote against the final passage of the Eleventh Amendment, standing with only nine others who opposed it. For Ward, protecting the ability of individuals to seek justice through the courts mattered. It was consistent with his lifelong belief that the law exists to serve ordinary people, not shield the powerful.

He retired from public service in 1797. He died in Shrewsbury on October 28, 1800. His death went largely unnoticed, a final insult to a man who had carried so much of the Revolution’s early burden. In the rush to celebrate national heroes, Ward quietly slipped from memory.

But his family refused to let his legacy fade. What followed was a century long struggle to restore his place in the American story. His descendants became guardians of his memory, shaping it, promoting it, and preserving it with stubborn devotion. They saw themselves as the keepers of a flame others had ignored.

His grandson Andrew Henshaw Ward began the work in the 1820s. A dedicated genealogist and historian, Andrew published local histories and placed a monument over Artemas Ward’s grave in 1847. He understood that without deliberate effort, the general’s contributions would vanish behind Washington’s towering shadow. Andrew tried to make sure his grandfather’s name stayed alive in the local consciousness.

The real caretakers of the memory, however, were the women of the Ward family. For generations they kept the general’s home, the Artemas Ward House, intact. Elizabeth, Harriet, Ella, Clara, and Florence preserved artifacts, protected documents, and told the stories that would otherwise have died with old age. They turned the house into a living museum, long before museums became the professionalized institutions we know today. Their labor kept the general’s world from falling apart board by board.

The last major revival came from his great grandson, also named Artemas Ward. This Ward was an advertising magnate with a keen sense of how memory could be shaped and sold. In 1921 he commissioned a biography to argue that the general should be remembered as the first Commander in Chief of the American Revolution. It was a bold move. Some embraced the idea. Others scoffed. But the argument gained traction.

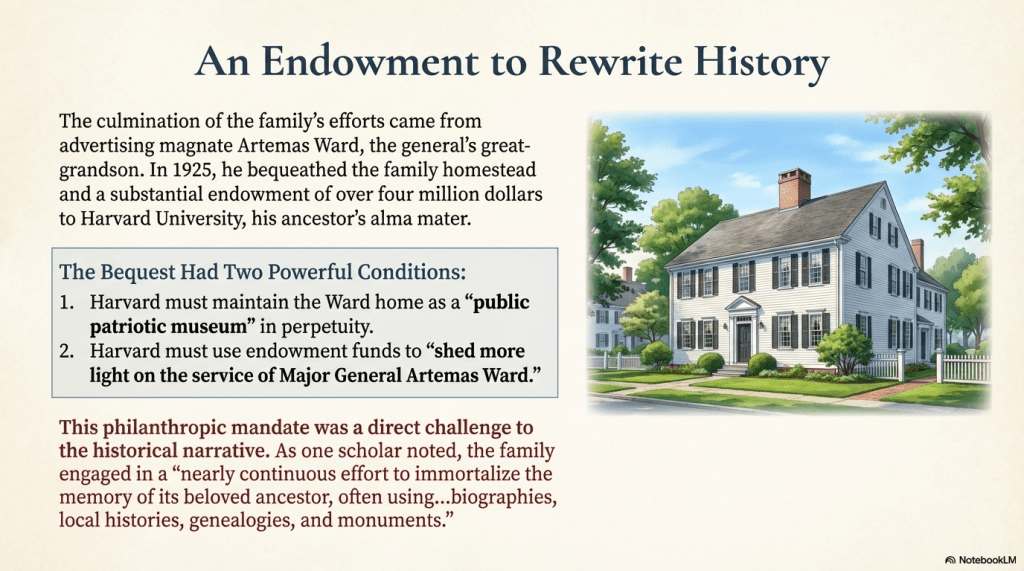

Then he purchased the family home outright and in 1925 donated it to Harvard University along with a large endowment. The donation came with non negotiable conditions. Harvard had to maintain the house as a public patriotic museum. And Harvard had to use funds to shed more light on the service of Major General Artemas Ward. In other words, Harvard had to keep the memory alive. The academy, whether it liked it or not, had to take Ward seriously.

The most visible result of this effort stands today in Washington D.C. in Ward Circle. A bronze statue more than ten feet tall was dedicated there in 1938. Harvard commissioned it, fulfilling part of the obligation created by the gift. But the statue tells a story of its own. The sculptor portrayed Ward as tall and commanding, a slender and majestic figure. This version of Ward bears little resemblance to the actual man, whom contemporaries described as round, dumpy, and paunchy. The statue is a reinvention of Ward, not the Ward his soldiers knew. Yet that is often how memory works. Families reshape their heroes to make them fit the national story.

Even the inscription on the statue tries to push his claim to prominence, stating boldly that Ward was the first commander of the Patriot forces. But the statue sits in a busy traffic circle, where few pedestrians can safely approach to read anything. It is a perfect metaphor for Ward’s legacy. He stands ready to be remembered, yet the world rushes past too quickly to stop and look.

Artemas Ward deserves far more attention than history grants him. He held the army together at its most vulnerable moment. He kept the siege lines around Boston intact despite political pressure and criticism. He pushed for the fortification of Dorchester Heights, which led directly to the British evacuation. He built the organization that Washington took command of. Without Ward’s steady hand in those early months, the Revolutionary cause might well have collapsed before Thomas Jefferson ever dipped his pen into ink.

Ward became a statesman when others might have retired. He governed Massachusetts in its most fragile years, upheld the rule of law during Shays’ Rebellion, served in the Continental Congress, and stood firm on matters of constitutional principle in the new federal government. He lived through every stage of the Revolution, from its messy beginnings to the first years of the Republic, always doing the work that needed doing.

His story is not one of glory. It is one of service. It is rooted in the old Puritan sense of duty, shaped by the failures of British command, and written in the quiet persistence of a man who stood guard while others collected fame. Washington became the face of the Revolution. Ward was the foundation that kept Washington’s army from slipping away before the fight even truly began.

The truth is simple. The Revolution needed a calm and cautious New England general in those early days. The cause needed someone who understood the terrain, the politics, and the people. Ward was the right man at the right moment. He saved the army long enough for Washington to lead it. He held the line when the world felt ready to spin apart. And though history has not granted him a loud voice, his steady whisper remains in every story of those first crucial months.

Leave a comment