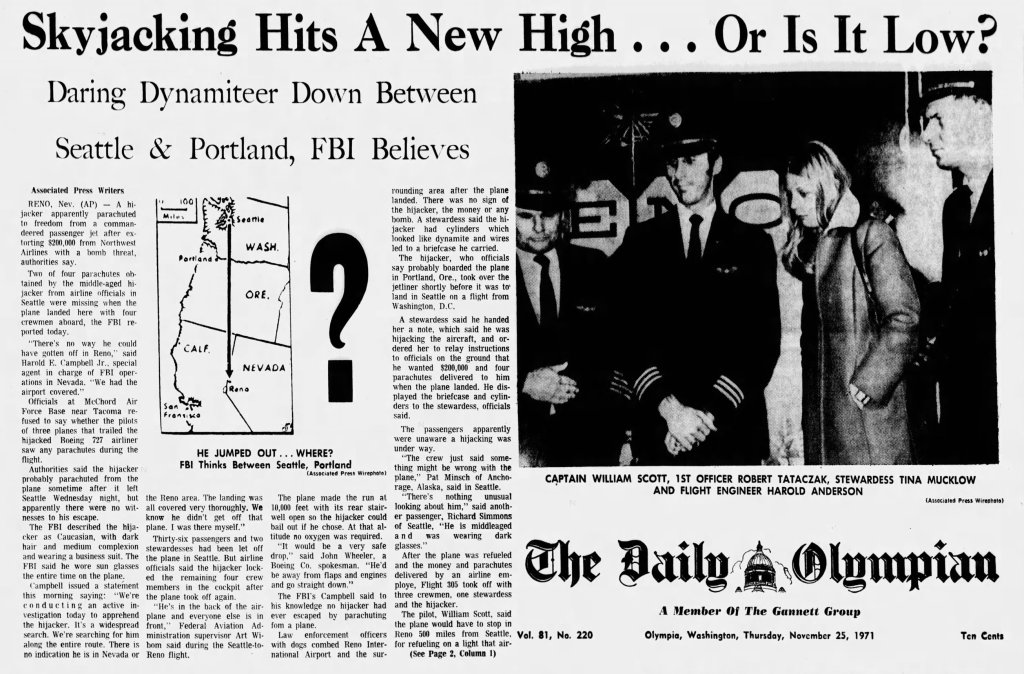

Thanksgiving Eve, 1971. While most Americans were carving turkeys or stuck in holiday traffic, a quiet man in a cheap suit and clip-on tie walked up to the Northwest Orient counter at Portland International Airport, paid twenty bucks cash for a one-way ticket to Seattle, and boarded Flight 305 like he belonged there. He gave his name as “Dan Cooper.” Nobody thought twice about it.

Three hours later he was gone, $200,000 richer, somewhere over the black forests of the Pacific Northwest, having pulled off the most audacious heist in American aviation history. He left behind a plane full of terrified passengers, four parachutes (two of which he didn’t take), a black J.C. Penney tie, and a legend that has refused to die for more than half a century.

In 1971, hijacking a plane wasn’t exactly rare. Between 1968 and 1972 the United States averaged one attempted skyjacking every five days. Most followed the same tired script: a desperate or deranged guy waves a gun, demands to be flown to Cuba, and usually ends up in custody after the plane lands for fuel. The airlines hated it, but the public treated it like an annoying weather delay. “Another one to Havana, pass the peanuts.”

Then came Dan Cooper.

He didn’t want Cuba. He didn’t scream or rant. He didn’t even raise his voice. He just passed a note to a pretty flight attendant, ordered a bourbon and 7-Up, and calmly explained that he had a bomb. When the plane touched down in Seattle, he traded 36 passengers for $200,000 in twenties and four parachutes. Then he told the crew to fly toward Mexico, low and slow, while he disappeared out the back with the money and a parachute, somewhere south of Ariel, Washington, on a stormy November night.

No body. No parachute. Almost no ransom money ever resurfaced. And no arrest. Ever.

The media botched the name in the first 24 hours. Some wire reporter heard “D.B.” instead of “Dan,” and the cooler, more mysterious version stuck. D.B. Cooper became an instant folk hero: the polite, brilliant everyman who beat the system and vanished into thin air.

Let’s walk through exactly how he did it, because the details are insane.

The man was in his mid-40s, about 6 feet tall, 170 to 180 pounds, dark wavy hair slicked back, olive skin, brown eyes. He looked like an accountant who had seen better days. Suit, white shirt, narrow black tie, loafers, black raincoat, dark sunglasses even though it was nighttime in Portland in November. He carried a cheap attaché case and a paper bag. Paid cash. No ID required back then.

Shortly after takeoff he handed flight attendant Florence Schaffner a note written in neat felt-tip capitals: “MISS, I HAVE A BOMB IN MY BRIEFCASE. I WILL USE IT IF NECESSARY. I WANT YOU TO SIT NEXT TO ME. YOU ARE BEING HIJACKED.”

When she tried to brush him off, he leaned in and whispered, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.” Then he cracked open the briefcase just enough for her to see four red cylinders (road flares), a mess of wires, and what looked like a battery.

He demanded $200,000 in negotiable American currency, specifically twenty-dollar bills, and four parachutes: two main back chutes and two emergency chest reserves. No marked bills, no dye packs, no funny business. He wanted the parachutes delivered by airline personnel, not cops. Why four? Smart move: it made the authorities think he might force a hostage to jump with him, so they wouldn’t dare give him duds.

Northwest Orient’s president, Donald Nyrop, didn’t hesitate. He paid. The FBI scrambled to photograph every serial number on microfilm (10,000 bills, 19 pounds of cash). While the plane sat on the tarmac at Sea-Tac, Cooper released the passengers, kept the crew, sipped his bourbon, and even offered to buy the crew dinner when this was all over.

Then he gave the pilots their new flight plan: Mexico City. Altitude no higher than 10,000 feet, landing gear down, flaps at 15 degrees, airspeed under 200 knots. Oh, and keep the cabin unpressurized, because he knew the rear airstair on a 727 could only be lowered in flight if the plane wasn’t pressurized.

That little detail floored the FBI. Almost nobody outside Boeing and certain military units knew the 727 had a rear door that could be opened mid-flight. Cooper wasn’t guessing. He knew.

Somewhere around 8:00 p.m., with the plane cruising at 195 mph over the Lewis River drainage, flight attendant Tina Mucklow, the last person to see him alive, watched Cooper tie what looked like the money bag around his waist with one of the reserve parachute’s shroud lines. He put on one of the back chutes (the non-steerable military type, he left the civilian sport chute behind), slipped on the raincoat, and walked toward the rear of the plane.

At 8:13 p.m. the tail lurched upward. Oscillations registered on the cockpit instruments. The aft stairs had just lost 180 pounds.

D.B. Cooper was gone.

The FBI codenamed it NORJAK, Northwest Hijacking, and threw everything at it. Over the next decade it became one of the longest and most expensive investigations in Bureau history.

Two F-106 fighters out of McChord AFB tailed the 727. They saw nothing. It was a moonless night, pouring rain, zero visibility under the clouds.

Ground searches started around Lake Merwin because that’s where the original projections put him. Later analysis, factoring in wind drift and the fact the plane was flying slower than the crew thought, moved the probable drop zone east, toward the Washougal River valley. Still nothing.

Agents collected 66 unidentified fingerprints from the plane (none ever matched a solid suspect). They kept the black clip-on J.C. Penney tie Cooper took off before jumping. In 2007 the FBI finally pulled a partial DNA profile from it. The tie also carried titanium smears and rare metal particles, stuff you’d find in aerospace manufacturing or certain chemical plants. One of the reserve chutes had its canopy cut away with a pocket knife, probably to wrap the money.

Nine years later, in February 1980, an eight-year-old kid named Brian Ingram was raking a sandbar on the Columbia River near Vancouver, Washington, when his shovel hit something rubber-banded and rotten. Three bundles of twenty-dollar bills, $5,800 total, still legible enough for the serial numbers to match the ransom list exactly. The spot became known forever as Tina Bar, named after the flight attendant who spent the most time with Cooper.

The money was buried just above the high-water line, and microscopic algae on the bills showed it had been submerged the following spring or summer, not November. That single discovery convinced most investigators that Cooper died on impact or shortly after, and the money washed down the Washougal watershed months later.

The FBI kept the case open for forty-five years. In July 2016 they finally moved NORJAK to inactive status, saying they needed the manpower for terrorism and other modern threats. The file still sits in headquarters, sixty-six volumes thick, waiting.

Over the decades the Bureau chased hundreds of suspects. A few rose to the top.

Richard McCoy Jr. pulled an almost identical 727 hijacking five months later, jumped with the cash, and got caught because he bragged too much. He was only twenty-nine, had light blue eyes, and looked nothing like Cooper. Ruled out.

Kenneth Christiansen was a former Army paratrooper who worked as a purser for Northwest Orient. He knew the 727 inside out, bought a house with cash right after the hijacking, and looked a little like the sketches. Crew members who knew him said no way, and the physical description didn’t match well enough for the FBI.

Robert Rackstraw was a slick ex-Army helicopter pilot with serious parachute experience and a long rap sheet. A team of citizen investigators spent years convinced he was the guy, claiming coded confessions and CIA cover-ups. The FBI looked hard at him in the 1970s and walked away unimpressed.

L.D. Cooper (no relation) was accused by his own niece after family Thanksgiving stories got weird. DNA from his guitar strap didn’t match the tie. Cleared.

William Gossett was a forestry worker and amateur hypnotist with jump training who told several people he was Cooper. No hard evidence ever put him on that plane.

The latest name to make serious noise is Vince Petersen (formerly William J. Smith), a railroad employee whose life story lines up eerily well with the metal particles on the tie, and whose photo looks like the composite sketch aged backward. The theory is still being worked by private researchers, but the FBI hasn’t reopened the file.

The big argument has always been: did he live or die?

If you ask most agents who spent years on the case, they’ll tell you he’s buried under a pine tree somewhere near Ariel. Night jump, freezing rain, 200-foot Douglas firs, dress shoes, business suit, no survival gear, and a non-steerable military chute he probably hadn’t touched since Korea or earlier. Odds were brutal.

Yet copycats like Martin McNally and Frederick Hahneman jumped under worse conditions and walked away. No body has ever been found. No parachute. No more money. And the guy was clearly no amateur.

The truth is we still don’t know.

What we do know is that Cooper terrified the airlines and the FAA into action. Within weeks every Boeing 727 got a little metal wedge welded to the airstair mechanism. They call it the Cooper vane. It physically blocks the stairs from lowering in flight. Problem solved.

Metal detectors showed up at airports for good in 1973. Cockpit doors got peepholes. Passenger screening became mandatory. The whole security theater we all complain about today started with a guy in loafers who just wanted two hundred grand and a ride into the night.

He also gave America something we didn’t have before: a real live folk hero who stuck it to The Man and got away clean. Books, movies, songs, conventions, even an annual party in Ariel where skydivers dress like 1971 accountants and jump into the same woods. Netflix and HBO keep making documentaries because every few years a new generation discovers the story and loses its mind.

The FBI says the case is closed unless someone brings them the parachute, the rest of the money, or a DNA match that can’t be argued with. The partial profile from that cheap black tie is still the best shot at ever putting a real name on the legend.

Until then, somewhere out there, the only successful skyjacker in American history is either laughing in his grave or still raising a quiet bourbon and 7-Up to the house.

Either way, happy Thanksgiving, Mr. Cooper. You magnificent bastard.

Federal Aviation Administration. 1972. “Airworthiness Directive 72-02-02: Boeing Model 727 Series Airplanes – Aft Airstair System.” Federal Register 37, no. 12 (January 20, 1972): 1016–17.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 1971–2017. “D.B. Cooper Hijacking (NORJAK).” FBI Vault. Parts 1–66. https://vault.fbi.gov/d-b-cooper.

Gray, Geoffrey. 2011. Skyjack: The Hunt for D.B. Cooper. New York: Crown.

Gunther, Max. 1985. D.B. Cooper: What Really Happened. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Himmelsbach, Ralph P., and Thomas K. Worcester. 1986. NORJAK: The Investigation of D.B. Cooper. West Linn, OR: Norjak Project.

Kaye, Thomas G., and the Citizen Sleuths Team. 2018. “Particle Evidence from the D.B. Cooper Tie: Titanium and Aluminum Alloy Particles.” Citizen Sleuths: The D.B. Cooper Case. June 12, 2018. https://citizensleuths.com/titanium-particles.html.

Kaye, Thomas G., Melanie L. Kaye, and Kay Havens. 2020. “Diatoms Constrain Forensic Burial Timelines: Case Study with DB Cooper Money.” Scientific Reports 10, article 13097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70015-z.

Porteous, Clark. 1971. “Mystery Hijacker Bails Out with $200,000, Vanishes.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 25, 1971.

Tosaw, Richard T. 1984. D.B. Cooper: Dead or Alive? Bend, OR: Tosaw Publishing.

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. 1972. United States v. Epperson, 454 F.2d 769.

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. 1973. United States v. Davis, 482 F.2d 893.

United States House of Representatives. Subcommittee on Transportation and Aeronautics. 1972. Aircraft Hijacking: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Transportation and Aeronautics of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., February 29–March 2, 1972. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Zenovich, Marina, dir. 2022. D.B. Cooper: Where Are You?! 4 episodes. Netflix. Los Angeles: Netflix.

Leave a comment