Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand Freiherr von Steuben was born on September 17, 1730, in Magdeburg, a city in the Prussian kingdom that today sits in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. The name itself carried a kind of thunder. It was long, complicated, and heavy with the weight of European nobility. He was the son of Wilhelm von Steuben, a captain in the Prussian engineers, and Elizabeth von Jagvodin. His father was an officer in a kingdom that was rapidly transforming into one of Europe’s most disciplined and feared military powers. It meant that young Friedrich’s childhood was steeped in martial traditions. His first memories were not of play or idle wandering but of the steady rhythm of marching boots and the careful calculations of artillerymen laying out their works. He was destined for war.

As a boy, he followed his father on assignments and spent part of his youth in Russia, where Wilhelm was serving with Prussian forces. Even before he was a soldier himself, Friedrich had seen campaigns. By the time he returned to Prussia, he had been exposed to the practical realities of warfare. He received a Jesuit education at Neisse and Breslau. The Jesuits did not just drill catechism into their pupils. They instilled discipline, attention to detail, and a devotion to structure. These were qualities that would serve von Steuben for life.

At sixteen or seventeen, he entered the Prussian Army. By then, Europe was in a near-constant state of war. The War of the Austrian Succession and soon after the Seven Years’ War shook the continent. The Prussian Army was the instrument of Frederick the Great, a monarch who transformed drill, discipline, and strategy into an art form. Von Steuben grew up under this system. He learned the value of precision and efficiency. He learned how armies could be turned into machines. By the time he was a second lieutenant in 1756, he was already part of the well-oiled force that Frederick had built.

The Seven Years’ War was a proving ground for him. He fought at Prague in 1757, where he was wounded. The battle was brutal. Smoke and confusion filled the air as the Austrians and their allies collided with Frederick’s men. Von Steuben was in the thick of it and took a wound that could have ended his career before it started. But he survived, and more than that, he advanced. In 1758 he became adjutant to General Johann von Mayr, a master of light infantry tactics. In 1759 he was promoted to first lieutenant and then wounded again at Kunersdorf. That battle was one of Frederick’s worst defeats, a bloody disaster against the combined forces of Russia and Austria. Von Steuben had seen both the glory of victory and the bitter taste of overwhelming loss.

He continued to rise. By 1762 he was a captain and served directly as aide-de-camp to Frederick the Great. That alone speaks volumes about the kind of officer he had become. To be near Frederick was to study the master at work. Frederick demanded brilliance and tolerated no fools. Von Steuben learned not just how to move troops on the battlefield but how to lead men, how to impose structure, and how to think about war as a complete system.

In 1763, when peace came, he was discharged. The official explanation is lost in the fog of time. Some said it was court intrigue, others suggested personal missteps. Whatever the reason, he found himself a professional soldier without a war and without a secure income. He was only thirty-three years old, seasoned by years of campaigning, and already bearing the scars of battle. But he was also restless, ambitious, and too deeply tied to the life of arms to retire quietly.

He became chamberlain to the Prince of Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Josef Friedrich Wilhelm. It was a noble title, one that carried with it dignity and social standing. Von Steuben wore it well. He attended court, he mingled with the elite, and he carried himself as a baron, a title he began using around this time. In 1769 he received the Cross of the Order of Fidelity from the Duchess of Württemberg. Yet behind the appearance of prosperity, he was struggling. The courtly life offered prestige but not money. He was drowning in debt. By 1775 he had even traveled to France with the prince in an attempt to borrow funds, returning to Germany with little to show for it other than more financial strain. Rumors circulated that he had left Hohenzollern-Hechingen under a cloud of scandal.

By the mid-1770s he was desperate. He sought military employment with Austria, with Baden, with France. Nothing came through. He was a soldier without an army. Then, in Paris in 1777, fortune shifted. He met Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, agents of the new United States. The Americans were fighting for independence, but their army was little more than a disorganized collection of volunteers. They needed professionals. Von Steuben saw his chance. Franklin and Deane, perhaps overstating his credentials, described him to George Washington as a “Lieutenant General in the King of Prussia’s service.” That was not accurate. He had left the Prussian Army as a captain. But it sounded impressive enough, and the Americans were willing to overlook the exaggeration because they needed help. Von Steuben offered his services without pay, a shrewd move given Congress’s distrust of foreign officers demanding high rank and money.

On September 26, 1777, he sailed from Marseille aboard the frigate Flamand. He landed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on December 1. He was not alone. With him were his greyhound Azor, his aide-de-camp Louis de Pontière, and his secretary Pierre-Étienne du Ponceau. He carried with him not only his European polish but also a willingness to reinvent himself in a new world. By February 1778, he was at Valley Forge.

The encampment was a scene of misery. Washington’s army was cold, hungry, and demoralized. Supplies were scarce, disease was rampant, and the men were poorly trained. Von Steuben arrived as a volunteer, but Washington recognized something in him immediately. He had presence. He had the bearing of a professional soldier. He also had a willingness to work. Washington gave him a chance.

What von Steuben found appalled him. The army was a shambles. There was no consistency in training. Men loaded and fired their muskets with sloppy motions. Officers failed to enforce discipline. Camps were laid out in chaos, with sanitation ignored. The soldiers fought bravely, but they lacked the discipline and skill to match British regulars. Von Steuben set out to change that.

He began by selecting a “model company” of about a hundred men, including members of Washington’s own guard. He trained them directly, drilling them in precise movements. Then those men trained others. He simplified the complex Prussian drills, reducing them to motions the Americans could master quickly. He broke down musket loading into eight steps, turning what had been confusion into efficiency. He insisted that bayonets be used aggressively, not just as cooking skewers but as weapons of decision.

Von Steuben did not sit back and issue orders. He marched with the men. He barked commands. He cursed in French and German when they blundered, and his aides translated his oaths into English, much to the amusement of the soldiers. They loved him for it. They saw in him not a distant nobleman but a man who would sweat with them, who cared enough to teach them himself.

The transformation was rapid. By the spring of 1778 the Continental Army was beginning to move like a real force. When they fought at Monmouth in June, they stood toe-to-toe with the British. The change was evident. Von Steuben’s system of progressive training had worked.

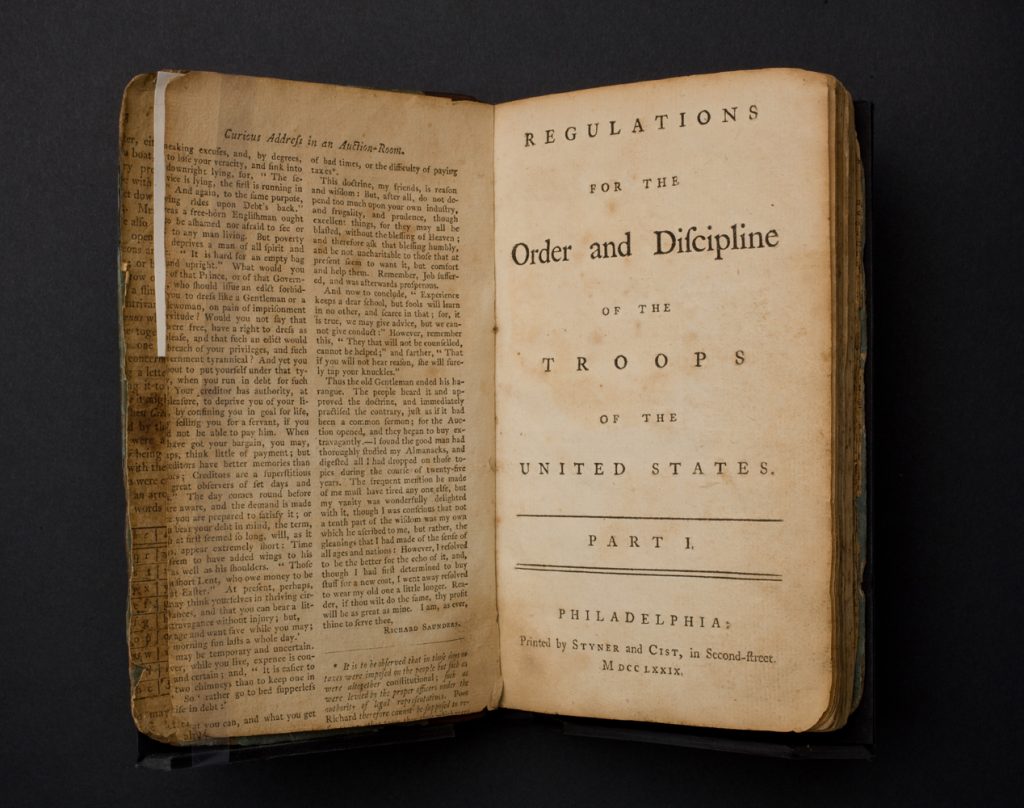

During the winter of 1778–1779 in Philadelphia, he wrote down his system in a manual titled Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. It became known simply as the Blue Book. Congress approved it in March 1779. For the first time, the American Army had a codified system of drill, organization, and officer duties. The Blue Book remained the official guide until 1814 and influenced practice well into the nineteenth century.

When June 1778 arrived, the newly drilled American army had its first true test at Monmouth, New Jersey. The sun blazed down on the fields, and the heat was so merciless that men dropped from exhaustion before the first volley was fired. British regulars moved with their usual precision, lines unfolding like a machine. Only months before, the sight of redcoats advancing would have sent the Americans stumbling backward in confusion. But this time the Americans stood their ground. Their muskets rose together, barrels glinting in the heat, and a volley thundered down the line in near perfect unison. Soldiers rammed cartridges home with crisp motions. They reloaded and fired again, not as individuals but as a body. When the order for bayonets came, they lowered steel points and surged forward with confidence. The British, who once mocked American clumsiness, found themselves checked and bloodied. Washington himself rode along the lines, proud of what he saw. He owed much of it to von Steuben, who had turned a mob into soldiers. At Monmouth, the transformation became real, proven under fire.

Listen to the Patrol Reports episode on the USS Von Steuben

Three years later, in October 1781, von Steuben commanded a division at Yorktown. The Franco-American army closed in on Cornwallis, and the British huddled behind earthworks by the river. Night after night, artillery hammered the defenses, the boom of cannon rolling through the Virginia air. Trenches crept closer to the British lines, dug by weary men under the cover of darkness. Von Steuben’s soldiers were among them, moving in careful order, cutting through the ground with the same precision he had once demanded on the parade field. When the time came to storm the redoubts, the troops advanced steadily. French allies took one, while Alexander Hamilton led Americans in seizing another. Chaos and courage mixed in the dark, with shouts, smoke, and musket flashes lighting the scene. Von Steuben’s men pressed the siege lines forward until Cornwallis had no escape. On October 19, the British marched out to surrender. It was the culmination of everything von Steuben had worked for. The discipline he instilled, the drills he demanded, and the structure he imposed had carried an army to final victory.

Von Steuben became one of Washington’s most trusted advisors. He served as chief of staff, reorganized supply systems, and inspected the army with a critical eye. In 1780 he was granted a field command and moved south with Nathanael Greene. He played a role in Virginia’s defense and later commanded a division at Yorktown in 1781, helping to deliver the final blow to British power in America.

When the war ended, he helped Washington with the delicate task of demobilizing the army. He was also present at the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati in 1783, the fraternal organization of Revolutionary War officers. On March 24, 1784, he was honorably discharged.

His postwar life was a mixture of honor and hardship. He was made a citizen first by Pennsylvania and later by New York. He received land grants, including 16,000 acres in New York, but he lived beyond his means. His generosity and extravagant style left him in debt. Friends like Alexander Hamilton helped him secure loans and eventually Congress granted him a life pension of $2,500 in 1790, enough to keep him comfortable in his later years.

Von Steuben never married. He had no children. Instead, he formed close bonds with his aides, William North and Benjamin Walker, treating them as adopted sons. When he died on November 28, 1794, at his estate near Rome, New York, he left his property to them. He was buried on his land, in a grove that later became Steuben Memorial State Historic Site.

His legacy is everywhere. He is remembered as the man who turned Washington’s volunteers into an army. He is honored as one of the fathers of the United States Army. The Blue Book set standards that endured for decades. His influence shaped the way American soldiers drilled, camped, and fought. Communities across the country bear his name. Statues of him stand at Valley Forge, in Washington, D.C., and in his native Germany. German-Americans celebrate Von Steuben Day every September with parades, beer, and pride in the man who came from Prussia and became an American hero.

It is easy to forget that revolutions are not won by declarations or lofty speeches alone. They are won by men who stand their ground in battle, who march in order, who know their weapons and trust their officers. In 1778, the American Revolution teetered on the edge of collapse. The army was in rags and the cause was in doubt. Then came a Prussian soldier, battered by wars in Europe, carrying the discipline of Frederick the Great’s army and the energy of a man determined to make himself useful. He arrived at the right place and the right time. He swore, he drilled, he wrote, and he transformed. That is why the United States remembers Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben not as a foreign adventurer but as one of its own.

Leave a comment