The Nullification Crisis of 1832 was a significant confrontation between the state of South Carolina and the federal government of the United States. At the heart of this conflict were two key issues: states’ rights and federal authority, set against the backdrop of contentious tariff laws.

The crisis began in earnest with the passage of the Tariff of 1828, often derisively referred to as the “Tariff of Abominations” by its Southern detractors. This tariff imposed heavy taxes on imported goods, ostensibly to protect American industry. However, it was deeply unpopular in the Southern states, particularly in South Carolina. The Southern economy was heavily reliant on the export of cotton and other agricultural products and relied on the import of manufactured goods. The tariff made these imports more expensive, which Southerners argued disproportionately harmed their economy and benefitted the industrial North.

The situation escalated when John C. Calhoun, then Vice President under Andrew Jackson and a South Carolina native, anonymously penned the South Carolina Exposition and Protest. In this document, Calhoun laid out the doctrine of nullification, arguing that states had the right to nullify federal laws that they deemed unconstitutional. The argument was grounded in a strict interpretation of states’ rights and the belief that the federal government was a creation of the states, hence not superior to them.

Tensions reached a boiling point in 1832 when South Carolina convened a special convention and declared the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within the state. This bold move challenged the federal government’s authority and brought the nation to the brink of a constitutional crisis.

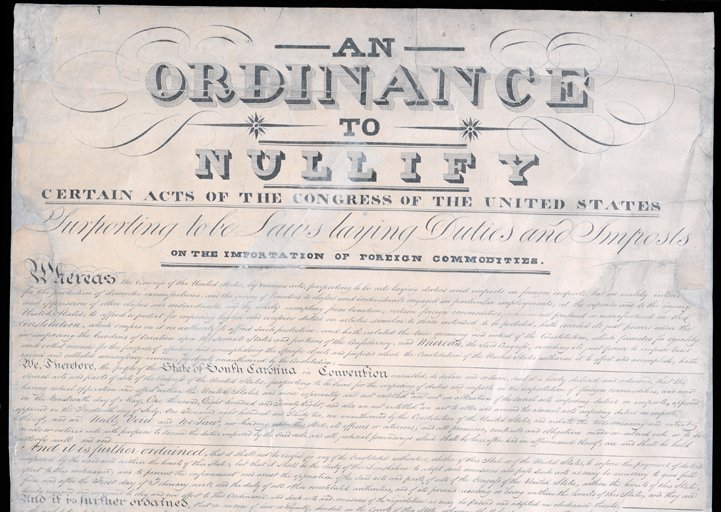

On November 24, 1832, in a bold challenge to federal authority, South Carolina adopted the Ordinance of Nullification, setting the stage for a significant constitutional crisis in the United States. This event was not just a local episode; it was a pivotal moment in American history, laying bare the contentious issue of states’ rights versus federal power.

The roots of the Nullification Crisis lay in the Tariff of 1828, dubbed the “Tariff of Abominations” by its Southern detractors. This protective tariff, aimed at supporting northern industries, inadvertently inflicted economic hardship on the Southern states, which relied heavily on the import of foreign goods and the export of agricultural products, primarily cotton.

The economic distress, coupled with growing sectional tensions, led South Carolina to take a radical step. Under the intellectual guidance of John C. Calhoun, then Vice President, the state adopted the theory of nullification. This doctrine posited that the states, being sovereign entities, had the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional and, by extension, refuse its enforcement within their borders.

On November 24, 1832, a specially convened convention in South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Nullification. This document declared the Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null, void, and non-binding in the state. The Ordinance was a direct affront to federal authority, effectively challenging the U.S. government’s ability to enforce its laws across all states.

The brinkmanship between South Carolina and the federal government led to heightened tensions, with fears of civil conflict looming. However, a compromise engineered by Senator Henry Clay, known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, gradually reduced the tariff rates and provided a face-saving mechanism for South Carolina to back down from its nullification stance.

The Nullification Crisis was more than a mere political skirmish; it was a critical test of the American constitutional framework. It highlighted the tensions inherent in a federal system where the balance of power between the states and the federal government was still being defined. The resolution of the crisis temporarily averted a larger conflict, but the underlying issues of states’ rights and federal authority would resurface in the coming decades, ultimately culminating in the Civil War.

The Ordinance of Nullification of 1832, therefore, stands as a significant episode in the complex tapestry of American history, exemplifying the perpetual struggle to define the nature of the Union and the extent of federal power in a system of divided sovereignty.

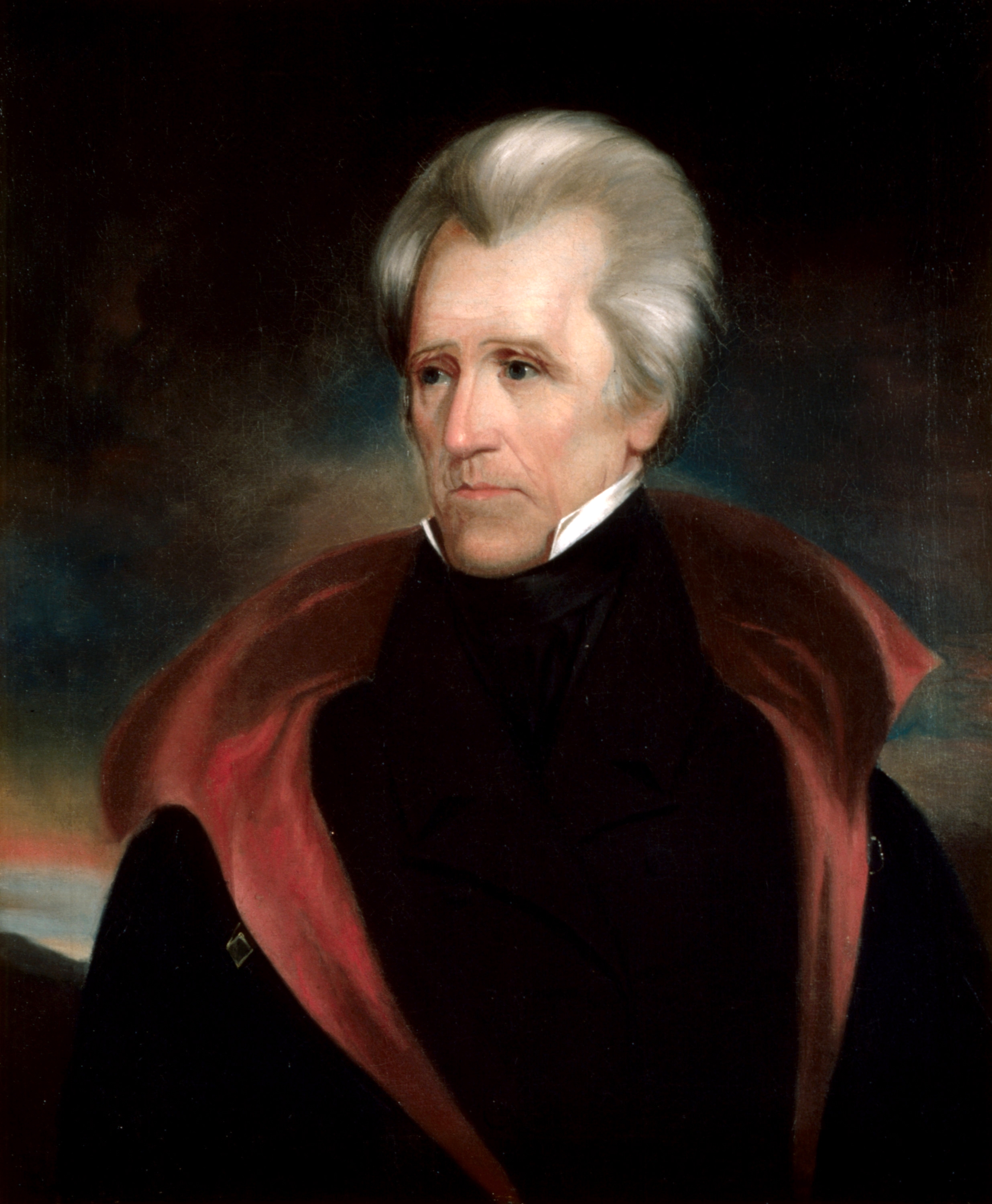

President Andrew Jackson, a staunch unionist, responded decisively. He viewed nullification as a direct threat to the Union and in December 1832, issued a forceful proclamation against South Carolina’s actions. Jackson denied the state’s right to nullify federal law or secede from the Union and prepared for military action, sending naval ships to Charleston harbor and threatening to hang anyone who worked to support nullification or secession.

An incident occurred at a Jefferson Day dinner in 1830, a few years before the height of the Nullification Crisis in 1832-1833, but it significantly foreshadowed the tensions that would soon escalate.

At this dinner, attended by many of the political elite of the time, toasts were given that were customary in such gatherings. President Andrew Jackson, a staunch defender of the Union, used his toast to subtly address the growing nullification sentiment, which was particularly strong in South Carolina, Calhoun’s home state. Jackson’s toast was short but pointed: “Our Federal Union: It must be preserved.” This statement was a clear message to nullification supporters, emphasizing Jackson’s commitment to maintaining the integrity of the United States.

In response, Vice President John C. Calhoun, a leading proponent of states’ rights and the nullification doctrine, gave his own toast. His words were equally charged and reflective of his political stance: “The Union, next to our liberty, most dear! May we always remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states, and distributing equally the benefit and burden of the Union!” Calhoun’s toast underscored his belief that the federal government should not overstep its constitutional bounds and that states had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional.

This exchange of toasts was not just a formal dinner tradition but a public display of the fundamental constitutional disagreement between Jackson and Calhoun. Jackson’s emphasis on the preservation of the Union contrasted sharply with Calhoun’s focus on the rights of the states. Their toasts symbolized the clash of ideologies that would soon lead to the Nullification Crisis, where these issues of states’ rights and federal authority would be contested in a more significant and confrontational arena.

The Nullification Crisis itself, which unfolded over the next few years, stemmed from this deep ideological divide and tested the limits of federal power and state sovereignty in the early years of the American Republic. The toast exchange between Jackson and Calhoun remains a vivid moment in American history, encapsulating the tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

To avoid a potential civil war, a compromise was brokered by Henry Clay in 1833. The Compromise Tariff of 1833 gradually reduced the rates of the abominable tariffs, providing some relief to the South. In return, South Carolina agreed to back down from its nullification stance. This compromise, while resolving the immediate crisis, highlighted the deep sectional divisions within the country, particularly over issues like states’ rights and federal authority, which would continue to fester in the lead-up to the American Civil War.

The Nullification Crisis of 1832 was more than a political standoff; it was a significant episode that tested the resilience of the United States Constitution and the Union. It underscored the complexities of federalism in America and set a precedent for the handling of states’ rights versus federal authority, a debate that would continue to shape the nation’s history.

Leave a comment