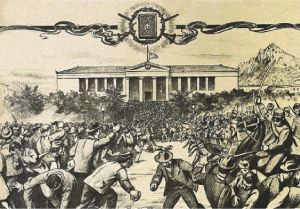

The Gospel Riots on November 8, 1901, in Athens stand as a pivotal moment in the history of the Greek Orthodox Church, embodying the tumultuous clash between modernity and tradition. This incident was not merely a spontaneous outburst of violence but a culmination of deep-rooted tensions within Greek society regarding language and identity.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of intense national awakening for Greece, which had gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s. The nation was in the throes of defining its cultural and national identity, and language became the battleground. At the heart of the debate were two forms of the Greek language: Katharevousa, a form which was artificially created to link modern Greece with its ancient past, and Demotic, the vernacular language spoken by the common people.

The push to translate the Gospels into Demotic Greek was driven by a desire to make religious texts more accessible to the lay population. Proponents of the translation movement argued that understanding the Holy Scriptures should not be the exclusive domain of the clergy or the educated elite who were fluent in Katharevousa or even classical Greek. They believed that in a truly democratic society, every individual should be able to read and comprehend the teachings of their faith.

Opponents viewed the translation of the Gospels into Demotic as an affront to the sacredness of the texts. They held the belief that the language of the church should be immutable, as it was a link to the Orthodox tradition and the glory of ancient Greece. The idea of altering the Scriptures to a simpler form of Greek was seen as a sacrilegious act that undermined the church’s authority and the nation’s connection to its illustrious ancestors.

Public Domain

The riots were marked by aggressive demonstrations and clashes with the police. Rioters, consisting of both laypeople and members of the clergy, took to the streets of Athens, decrying the translations and demanding that the government uphold the sanctity of the church’s linguistic tradition. Government buildings were besieged, public properties were damaged, and the unrest led to numerous injuries as authorities struggled to restore order.

The Greek Orthodox Church found itself in a difficult position, caught between the forces of modernization and the defenders of tradition. Initially, the church hierarchy expressed disapproval of the translations, echoing the sentiments of the rioters. However, as the violence escalated, the church leadership called for peace and dialogue, emphasizing the need for unity within the faith community.

The aftermath of the Gospel Riots was a period of reflection and reconsideration for the Greek Orthodox Church and the Greek state. The controversy led to a wider debate about the role of religion in education and the state’s involvement in religious matters. It also sparked discussions on the importance of language in national identity and the need for a balance between preserving tradition and embracing change.

The legacy of the Gospel Riots is multifaceted. On one hand, they underscored the deep attachment to the Hellenic past and the symbolic power of language in Greek culture. On the other, they highlighted the challenges that arise when a society strives to navigate between its revered traditions and the practical needs of its people. In the long run, the riots set the stage for gradual reforms in the church’s approach to language, contributing to the eventual acceptance of Demotic Greek in various aspects of public life, including religious practice.

The Gospel Riots thus remain a significant episode in the history of modern Greece, encapsulating the tensions between tradition and modernity that were—and to some extent, still are—at the heart of Greek national identity.

Leave a comment